| The Public Paperfolding History Project

Last updated 22/3/2024 x |

|||||||

| A Brief History of Educational, Decorative and Recreational Paperfolding in Europe and the Americas after the Death of Froebel in 1852 | |||||||

Introduction By educational paperfolding I mean paperfolding intended to act as a means of education. By decorative paperfolding I mean paperfolding used to create items intended to be used as ornaments or decorations for the home or elsewhere. By recreational paperfolding I mean the activity of folding paper to amuse or entertain oneself or others, or to create toys or puzzles, or to facilitate the playing of games. ********** This page takes the story of the development of recreational and educational paperfolding history forwards after the death of Froebel in 1852. He died soon after the suppression of kindergarten education in the state of Prussia in 1851 for political reasons, with other German states following suit. This suppression led to many of Froebel's followers leaving these states for other countries. Another important date is 1867, the date at which Japanese recreational paperfolding designs first begin to appear in the West, initially in France. However, this date does not mark an abrupt watershed. It took time for the few Japanese designs that reached the West to become well-known and even longer for them to exert an influence on the creation of new recreational designs, through the realisation that the base forms of the Paper Crane and the Blow-up Frog, what we now call the bird base and frog base respectively, could be developed into many other designs as well. It is difficult to evaluate the extent to which recreational paperfolding permeated popular Western culture during this period. Most probably, the situation was much as it still is today. Most people, perhaps, knew one or two simple paperfolds off by heart (though which ones these were would probably have varied between indivifuals and changed over the years) and may also have folded paper as an occasional pastime as and when a newspaper or magazine article, or a book caught their attention. A much smaller number of people may well, as they do today, have folded paper rather more regularly, as a hobby, or as therapy, and learned a rather wider repertoire of folds. Of these, some few may have developed an enthusiasm that went beyond a mere hobby, and may, perhaps, also have discovered a facility for creating their own designs. Throughout much of this period these enthusiasts largely seem to have folded in isolation, until the formation of the origami societies provided a way for them to develop contacts with each other. Froebel’s original conception of the three paperfolding occupations, Falten (Folding), Ausschneiden und Aufkleben (Cutting out and Mounting) and Verschnüren (Interlacing), four if we count Flechten (Weaving), seems to have been that they should be quite limited in their scope. All the occupations had a specific purpose. They were not general activities to provide interest for children in the kindergarten classroom, but activities intended to allow the child to acquire specific cognitive skills and knowledge. In practice, however, over the years, the original concepts of these occupations were broadened, and new paperfolding material, frequently unrelated to the original concepts, was added. In addition, entirely new paperfolding occupations were added to the original four. Kindergarten teachers also developed a repertoire of much simpler folded Forms of Life which provided an introduction to paperfolding for the youngest children. Many books containing paperfolding material were published during this period, and many articles explaining paperfolding designs were published in periodicals and magazines. To include even a short description of them all would result in this brief history not being brief at all, but I have tried to provide at least a link, even if only as part of a list of such links, which will enable you to look up further details should you wish to do so. I have not included links to works I know exist but have not seen since no evaluation of their content of influence is possible. ********** A: The Cocotte (again) While knowledge of how to fold the Cocotte was not limited to the French, it was in France, both before and after 1851, that images featuring Cocottes appeared most regularly. The Cocotte was often shown as what it originally was, a children's toy, but was also be used as a symbol of childhood or childishness. The word ‘cocotte’ was also used to mean a fairly high-class prostitute, and images of paper cocottes were often used in cartoons and caricatures referencing this meaning. The design of the Cocotte is most usually interpreted as a bird, but it was also often seen as a horse (or perhaps a hobby-horse) and images of people riding Cocottes as though they are horses are common. It is also surprising, given how well known it was, that the Cocotte is often shown in a distorted form. Here are a selection of images showing the Cocotte in its various guises: ********** This painting by P. Petrov, which can be dated to around 1855, shows a child with a book, ball and a Cocotte.

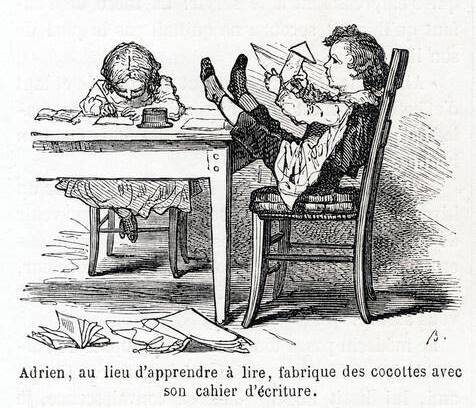

********** This illustration by Bertall (1820-1882), which appeared in 'Children s Week' of June 20, 1857, includes a Cocotte with a neck that is far too long.

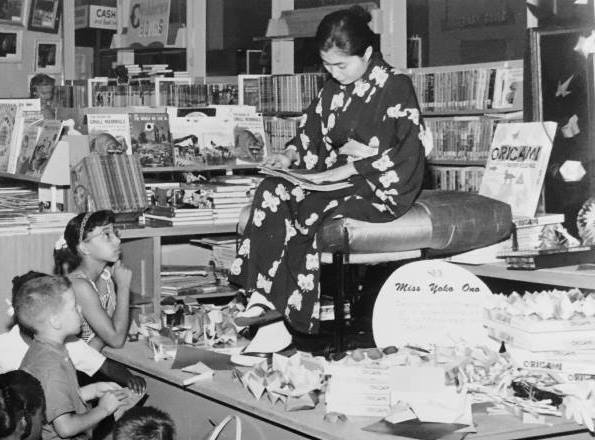

********** The pornographic novel 'Souvenirs d’une cocodette', supposedly a memoir by the main character, Aimee, but in fact by Ernest Feydeau, and first published in Paris in 1870, contains a frontispiece showing a Cocotte covering, or perhaps censoring, the nakedness of the cocodette of the title. ********** This caricature drawn by Louis Malteste (1862-1928) appeared on the back cover of the 9th March 1902 issue of the satirical magazine 'La Vie en Rose’. It shows Leopold II of Belgium riding a Cocotte. The crossed out 'C' that makes the name 'Cleopold' seems to be a reference to the ballet dancer Cleo de Mérode, who was rumoured to be his mistress.

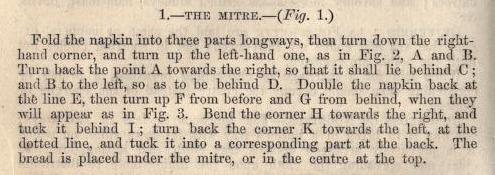

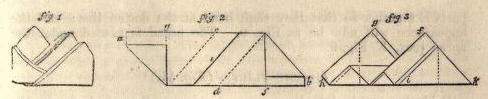

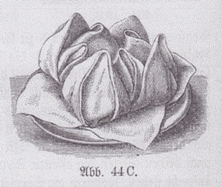

********** B: Napkin Folding (again) By 1851 the folding of napkins and serviettes was no longer about the creation of elaborate table decorations and centrepieces but about the folding of napkins intended for diners personal use into decorative place settings, that might also act as a holder for a bread roll. Some of these designs subsequently became part of the recreational paperfolding repertoire (something which we have already seen happened with the Cross). ********** Diagrams for the design, called the Mitre, Bishop's Mitre or Pipecap, first appear, as a napkin fold, in 'The Practical Housewife' by Robert Kemp Philp, which was published in London by Ward & Lock in 1855.

More information about this topic will be added in due course. ********** The Lotus first appears as a napkin fold in 'Des Kindes Erste Beschaftigungsbuch' by E Barth and W Niederley, which was published in Bielefeld and Leipzig in 1876.

********** C: The Spread of Froebelian Ideas - Political Exiles and Early Promoters - 1851 to 1862 The main promoter of Froebelian ideas following Froebel's death was undoubtedly the Baroness von Marenholtz, although there were others, notable among them August Koehler, who also made a significant contribution to the spread of his methods. There is no indication that the Baroness von Marenholtz was among those who had to leave Germany for political reasons. The information about her 'missionary' activities given below is mostly taken from 'The Life of the Baroness Marenholz-Bulow', by her neice, Baroness von Bulow, available online here. The information about the number of kindergartens using the Froebelian method in various countries in 1862 is taken from 'Manuel Theorique de la Reform Educative de Frederic Froebel' by Edward Raoux.. The number of kindergartens that could be opened was very dependent on the number of teachers who could be trained in Froebel's method. According to Raoux, in 1862, there were only 6 Ecoles Normales where such teachers could be trained, all in Germany.

********** i. In England In 1851, for political reasons not directly related to their involvement with the kindergarten movement, Johannes and Bertha Ronge, (formerly Bertha Meyer), and her sister Margarethe Meyer, left Germany for London where, also in 1851, the Ronges set up the first kindergarten to be founded in England in their home in Hampstead. In 1853 the school moved to a more central position in London at 32 Tavistock Place in St Pancras. In 1854 the Society of Arts held an Educational Exhibition at which Froebelian materials supplied by the Baroness von Marenholtz were exhibited. The Baroness spent much of 1854 in London, along with the Countess Krokow, who spoke better English, promoting Froebel's ideas and wrote her 'Woman's Educational Mission: Being an Explanation of Frederich Froebel's System of Infant Gardens' which was published in early 1855, and which included brief explanations of the nature of Froebel's four paperfolding occupations. The Translator's Preface mentions that another of Froebel's pupils, Heinrich Hoffman was also in London promoting Froebel's methods at that time. Later in 1855 Johannes and Bertha Ronge published their own kindergarten manual, titled 'A Practical Guide to the English Kinder Garten'. Inter alia, it contains information about 'Cutting Out' (the occupation of Ausschneiden und Aufkleben), some brief examples of basic mathematical folding and some brief comments on the folding of Forms of Life, which are reproduced below. It is notable that children are 'allowed at first to form any object at pleasure'.

Unfortunately there are no illustrations of the forms of 'box, basket, ship, boat, stars' mentioned here and consequently the exact designs referred to cannot be identified. ********** In July 1855 an article about 'Infant Gardens' appeared in Charles Dicken's 'Household Words' which gave information about Friedrich Froebel, his educational theory, gifts and occupations and mentions Baroness von Marenholtz, Heinrich Hoffman and the Ronge's kindergarten etc. ********** According to Raoux (see above), the kindergartens open in England by 1862 were:

********** ii. In France and Belgium The Baroness von Marenholtz spent most of 1855/7 in France and 1858 in Belgium. She gave many lectures in Paris and appears to have succeeded in interesting several existing institutions in adopting at least part of the Froebelian method, akthough the lackof trained teachers appears to have prevented the opening of kindergartens per se. She arrived in Brussels in December 1857, soon after the first kindergarten was opened there by a Mme Guillaume (who had trained in Hamburg). Shortly after this the Froebel method began to be used in other schools, with the encouragement of the Minister for Education. in 1858 Baroness von Marenholtz's book 'Les Jardin's D'Enfants: Nouvelle Methode d'Education et d'Instruction de Frederic Froebel' was published in Brussels and Ostend. It contains nothing about paperfolding except this short passage (roughly translated): 'In another cupboard we see collections of geometrical or fancy figures, made by folding a square piece of paper. It is a progressive series of one hundred and twenty pieces. Each form emerges from the previous one. The various folds children make prepare them for the study of geometry and the hand achieves amazing dexterity', which is presumably a reference to Folds of Beauty. 1859 saw the publication of the 'Manuel pratique des jardins d'enfants de Frédéric Froebel', 'compose sur les documents Allemands' by J F Jacobs, and published in Brussells and Paris. The Baroness von Marenholtz provided a Preface but her biography (cited above) says that she was much more heavily involved than just that:

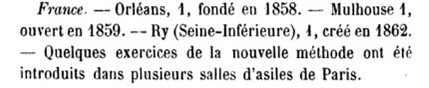

The contents of this book are discussed in a separate section below. ********** According to Raoux (see above), the kindergartens open in France and Belgium by 1862 were:

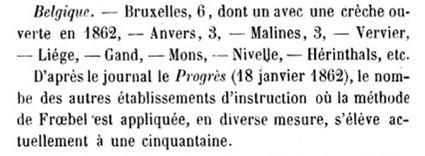

********** iii. In The Netherlands The Baroness von Marenholtz was in the Netherlands for a few months in the Summer of 1858, when she met Elise van Calcar, by then already an established author. Thereafter, Elise van Calcar seems to have thoroughly embraced Froebelian ideas. She subsequently wrote a series of four books under the general title 'De Kleine Papierwerkers' which were based around Froebel's occupations of paper pricking, weaving, folding and cutting out, although they also included much additional material. (See separate section below.) According to Raoux (see above), the kindergartens open in the Netherlands by 1862 were:.

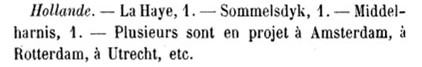

********** iv. In Switzerland The Baroness von Marenholtz was in Switzerland at various times during 1856 to 1860. Here is a relevant extract from Baroness von Bulow's book (cited above):

Baroness von Marenholtz's book 'Les Jardins d'Enfants' was published in Lausanne in 1860. It is very similar to her 1858 volume (see above). ********** In 1862 Edward Raoux published his own book, 'Manuel Theorique de la Reform Educative de Frederic Froebel' which contains a good summary of the spread of Froebelian ideas up to this date. According to Raoux (see above), the kindergartens open in Switzerland by 1862 were:

********** v. In Germany The ban on Froebelian education in Prussia was lifted in 1860. According to Raoux (see above), the kindergartens open in Germany by 1862 were:

********** vi. In Italy According to Raoux (see above) there were no kindergartens open in Italy by 1862:

********** vii. In Russia According to Raoux (see above), the kindergartens open in Russia by 1862 were:

********** viii. In Denmark According to Raoux (see above) there was just one kindergarten open in Denmark in 1862 and another planned:

********** ix. In Spain According to Raoux (see above) there was just one kindergarten open in Spain in 1862:

********** x. In the USA In 1851 Margarethe Meyer, sister of Bertha Ronge, met Carl Schurz, another political exile, in London. They married and emigrated to the USA in 1852. In 1856 Margarethe Schurz opened the first kindergarten to be established in the USA. The children who attended were German-speaking and lessons were conducted in that language. In 1859, Margarethe introduced Elizabeth Peabody, who subsequently set up the first English-speaking kindergarten in the USA, to Froebel's ideas . Adolf Douai, who had served three years in prison for his political activism, also emigrated to the USA at this time. Later, in Boston, he established a German workingmen's club which in 1859 sponsored a three-classroom school featuring the first American Kindergarten' (Wikipedia). ********** According to Raoux (see above), the kindergartens open in the USA by 1862 were:

********** D: Manuel pratique des jardins d'enfants de Frédéric Froebel, 1859 Information about the authorship of this book taken from 'The Life of the Baroness Marenholz-Bulow', by her neice, Baroness von Bulow, is available online here, but repeated below.

This book was very influential. This passage mentions a Dutch translation but there are also said to be translations into English and German, although I have not been able to locate any of them. As the passage notes it was also the foundation of 'Der Kindergarten' by Hermann Goldhammer, published in 1869, which in turn formed the basis of Edward Wiebe's 'Paradise of Childhood', which was published in the USA in the same year.

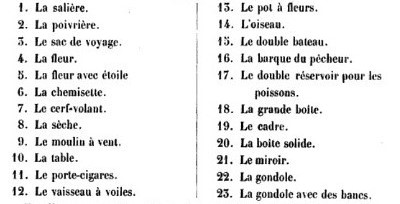

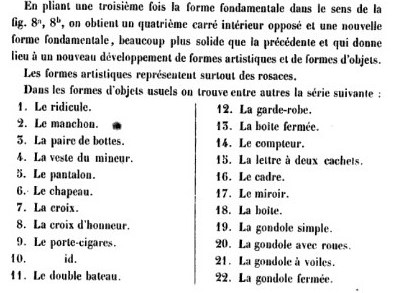

A revised edition of 'Der Kindergarten' was issued in 1874. Some of the illustrations from the revised edition were redrawn and republished in the earliest kindergarten manual to be published in Japan, the 'Yochien Ombutsu No Zu'. ********** 'Manuel Pratique' explains Froebel's method of obtaining four squares from a rectangle, as well as information about L'Entrelacement (Verschnüren), Le Decoupage (Ausschneiden und Aufkleben) and folded Forms of Beauty (derived from Froebel's first groundform - the blintzed square). However, from a historical viewpoint, the main interest is the information it gives about folded Forms of Life, the first time such information appears in the historical record. This information is in the form of two lists of names of designs. There are no accompanying illustrations. List 1:

List 2:

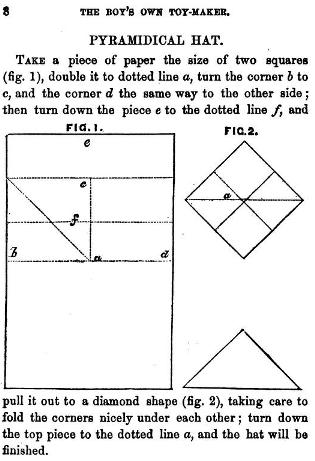

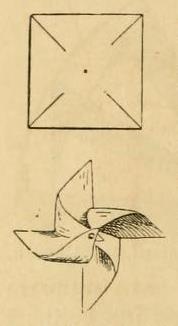

It should immediately be clear that the designs in List 1 are derived from doubly blintzed starting shapes (whch correspond to Froebel's second groundform) and those in List 2 from a triply blintzed form (which corresponds to Froebel's third groundform). Many of the now famous designs in both lists appear here for the first time, including: In List 1: The Saltcellar (La saliere), the Pepperpot (La poivriere), the Windmill (Le moulin a vent), the Table (La table), the Cigar Case (Le portes-cigares), the Vase (Le pot à fleurs), the Solid Box (La boite solide) and the Gondola (La gondole). In List 2: The Muff (Le manchon), the Jacket (La veste du mineur), and the Trousers (Le pantalon), Not all the designs in either list can be identified at present. It is perhaps worth noting that item 20 in list 1, 'La boite solide' (the Solid Box) is the design known to present day paperfolding enthusiasts as the 'Un-unfoldable Box', a design usually attributed to E D Sullivan, who rediscovered it in the modern era. This book also contains the earliest known description of how to cut a Fold and One Cut Hexagon from a square. ********** D: Paperfolding in Education - 1862 onwards In its original conception, paperfolding within Frobel's kindergarten system, can be characterised as 'paperfolding as an aid to cognitive development', and in some countries, educational paperfolding in this guise survived for some time after 1862. However, Frobel's original paperfolding occupations of 'Falten' (paperfolding per se), 'Verschnuren' (the interlacing of paper strips) and 'Ausschneiden und Aufkleben' (Cutting Out and Sticking On) were quickly subject to a process of enhancement and reinterpretation. New material was added to the original occupations and additional occupations that made use of at least some element of paperfolding were invented. In addition, educationalists in several countries attempted to extend the use of the occupations to the education of older, sometimes significantly older, children. In general the long-term trend was towards simplification of the original material, since it could not be used effectively except within Frobel's own framework of practice, which was also being lost. In the English speaking countries in particular, Paper Sloyd, and adaptation of the original Swedish Slojd with its emphasis on practicality rather than imagination, eventually came to largely replace other kinds of paperfolding within the curriculum. In addition, in many countries educational paperfolding as a means of cognitive development was quickly subsumed by the desire of the government to prepare children, especially boys, to become skilled manual labourers, of whom there was a significant shortage. Lessons in 'manual training' (ie largely manual dexterity in using tools) were introduced into schools, and paperfolding was often included in these lessons, largely on the basis that paper was easily available and that folding it did not require special facilities such as expensively fitted out workshops. In some countries paperfolding was also used as a means of teaching some simple mathematics and in the USA as a means of teaching art. Paperfolding also featured as a way of teaching design at the Bauhaus and subsequently at Black Mountain College in the USA. After 1862 the trajectory of the use of paperfolding in education was different in each country. I have made pages to collect information about these differing trajectories and information will be added to them as and when I have time. However, at present, they are largely empty. Paperfolding in Education in Argentina 1852 onwards Paperfolding in Education in Austria 1852 onwards Paperfolding in Education in Belgium 1852 onwards Paperfolding in Education in Denmark 1852 onwards Paperfolding in Education in England 1852 onwards Paperfolding in Education in France 1852 onwards Paperfolding in Education in Germany 1852 onwards Paperfolding in Education in Italy 1852 onwards Paperfolding in Education in the Netherlands 1852 inwards Paperfolding in Education in Spain 1852 onwards Paperfolding in Education in Russia 1852 onwards Paperfolding in Education in Switzerland 1852 onwards Paperfolding in Education in the USA 1852 omwards ********** E: Recreational paperfolding in books and magazines for girls and boys - 1852 to 1899 Details of the earliest books of games and occupations for boys and girls to contain instructions or diagrams for recreational paperfolding designs were given in part 1 of this brief history. Similar books continued to be published, in several languages, throughout the remainder of the nineteenth century. i. In English The Boy's Own Toymaker by E Landells, 1859 'The Boy's Own Toymaker' by Ebenezer Landells, which was published in London and Boston in 1859,contains the earliest known diagrams for the 'Pyramidal Hat' (which is derived from the Newspaper Hat).

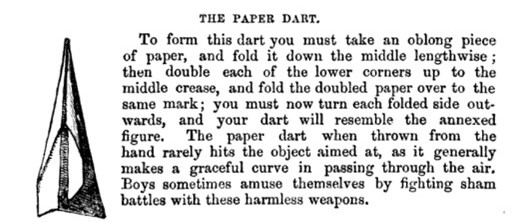

********** Games and Sports for Young Boys, 1859 'Games and Sports for Young Boys' was published by Routledge, Warne and Routledge in London and New York in 1859. The earliest known instructions for making the classic Paper Dart design appear in this book.

********** The Girl's Own Toymaker by E Landells and Alice Landells, 1860 'The Girl's Own Toymaker' by Ebenezer Landells and Alice Landells which was published in 1860, contains the earliest known diagrams for the sixteen-fold symmetry design we now know as the 'The Fold and Cut Paper Doily'.

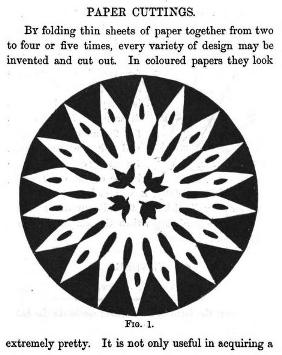

********** ********** ********** The Boy's Own Book (Revised Edition), 1880 ********** Cassell's Book of Indoor Amusements, Card Games and Fireside Fun, 1881 ********** Articles in St Nicholas magazine - 1881 onwards A number of articles about recreational paperfolding were published in the American children's magazine 'St Nicholas', from 1881 onwards. In 1881 St Nicholas magazine published a reader’s letter explaining and illustrating the Newspaper Ladder (the earliest known appearance of this design). The same issue also included diagrams for the Fold and One Cut Latin and Maltese Crosses, which also showed how to arrange all the pieces released by cutting out the Latin Cross to form an Altar (the first time this particlar arrangement of the pieces is known to have been published) In 1887 St Nicholas magazine published another reader’s letter explaining how to make a Japanese design, the Sanbo on Legs, under the somewhat surprising name of 'Nantucket Sinks'. This is the first known appearance of this design in the West. ********** The American Girls's Home Book of Work and Play by Helen Campbell, 1883 ********** Articles in The Boy's Own Paper - 1886 onwards A number of articles about recreational paperfolding were published in the British children's magazine 'The Boy's Own Paper', from 1886 onwards. In 1886 the Boy’s Own Paper published an article showing how to fold the Flapping Bird (a translation of the 'La Nature' article from 1885, see below) and a written description of how to make the Chinese Junk. In 1891 the Boy’s Own Paper published an article showing how to fold the Kettle under the title 'How to Boil Water in a Paper Bag'. As far as I know this is the earliest appearance of this design in the literature. ********** Pleasant Work for Busy Fingers by Maggie Browne, 1891 ********** ii. In Dutch De Kleine Papierwerkers by Elise Van Calcar, 1863 'De Kleine Papierwerkers' (The Little Paperworkers), was a series of four books written by Elise van Calcar which were published in Amsterdam in 1863. Volume 3: Het prikken (Pricking) has no paperfolding content. ********** Volume 1: Wat men van een stukje papier al maken kan: Het vouwen (What one can make from a piece of paper: Folding) contains material about mathematical paperfolds (Forms of Beauty) and folded Forms of Life (but not Forms of Beauty). The first chapter of the book is a story wherein a youthful Aunt Mina amuses seven of her nieces and nephews by teaching them to fold things out of paper. The rest of the book is a straightforward description of the Froebelian method as applied to paperfolding. This book does not restrict itself to designs produced from the Froebelian groundforms, but introduces folds made in all kinds of other ways. A good number of these designs, among them the Waterbomb ('De teerling' - the die) and its derivative the Hot Air Balloon (De luchtballon), the Steamship (here called 'Der inktkoker' - the well), and the Talking Fish (De haai - the shark) appear here for the first time, as does an alphabet folded from paper strips.

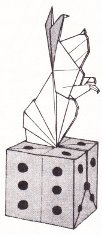

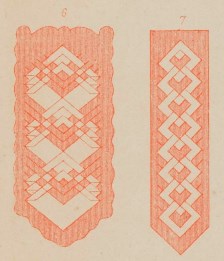

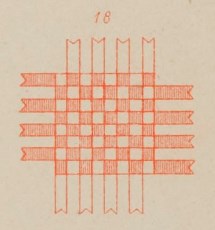

********** Volume 2: Wat men uit strookjes papier al vlechten kan (What one can braid from strips of paper) seems to depart almost entirely from the content of the original Froebelian occupations. There is an illustration of a design made by interlacing two folded strips of paper, but as far as I can tell this is not mentioned in the text. Instead the book introduces various other techniques for folding with paper strips including the Free Weaving Folded Strips, making Fold, Slit and Fold Chevron Designs, making and combining Froebel Stars. There is also an illustration of the Witch's Ladder, though no folding instructions are given.

********** Volume 4: Het Knippen en plakken (Cutting and Pasting) is mostly about the Froebelian occupation of Ausschneiden und Aufkleben but with the addition of a few other unrelated fold and cut designs, including the earliest known instructions for making the Fold and Slit Paper Cage / Fishing Net. ********** A follow up volume on cardboard modelling, 'De Fröbelsche kartonwerkers. Handleiding tot het vervaardigen van allerlei soort van kartonnage' was issued by the same publisher in 1864. ********** De Jonge Werkman: Het Vlechten by Elise Van Calcar, 1881 ********** iii. In German 'Spielbuch fur Knaben' by Hermann Wagner, 1864 'Spielbuch fur Knaben' (Playbook for Boys) by Hermann Wagner was published in Leipzig in 1864. It contained an almost full page illustration of paperfolding designs (reproduced below), which was subsequently to be reproduced in many other books, and various other paperfolding related designs scattered throughout the rest of the book.

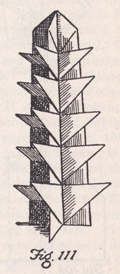

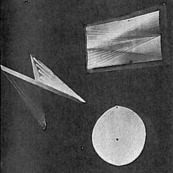

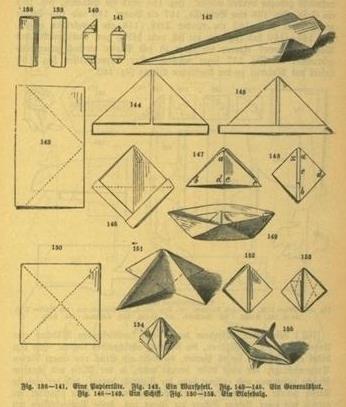

This is the earliest known publication of diagrams for the Hexagonal Packet (top left), although earlier surving examples of actual folded packets of this design are known. The same book also contains the earliest known diagrams for the Cut and Fold Windmill.

********** 'Spielbuch für Mädchen' by Marie Leske, 1865 'Spielbuch fur Madchen' (Playbook for Girls) by Maria Leske (a pseudonym of Marina Krebs), which was published in 1865, contained many of the same paperfolds as 'Spielbuch fur Knaben'. ********** Das Deutschen Knaben Handwerksbusch by Barth and Niederley, 1872 ********** 'Des Kindes Erste Beschaftigungsbuch' by E Barth and W Niederley, 1876 'Des Kindes Erste Beschaftigungsbuch' (The Child's First Activity Book) by E Barth and W Niederley was published in 1876. It is not a Froebelian manual, but a follow-up, aimed at younger children, to the author's 'Das deutschen Knaben Handwerksbusch'. This book was translated into Dutch by Elise Van Calcar and published by A.W. Sijthoff in Leiden in 1881 under the title 'De Jonge Werkman: Het Vlechten'. The illustrations in both works are identical. An English version of this book was published as 'Pleasant Work for Busy Fingers' by Maggie Browne in 1891 (see above). ********** Spiel und Sport by Dr Jan Daniel Georgens, 1882 ********** Spiel und Arbeit by Hugo Elm, 1885 ********** Neues Spielbuch fur Madchen by Jeanne Marie von Gayette-Georgens, 1887 ********** Spielbuch fur Kinder by Ida Bloch, 1891 ********** iv. In French Les Récréations Scientifiques by Gaston Tissandier, 1880 to 1888 ********** Un million de jeux et de plaisirs by T de Moulidars, 1880 ********** Popular Scientific Recreations by Gaston Tissandier, 1883 ********** Jeux et Jouet du Jeune Age by Gaston Tissandier, 1884 ********** La Science Pratique by Gaston Tissandier, 1889 ********** Travaux Recreatifs Pour les Enfants de 4 a 10 Ans by Marie Koenig, 1898 ********** La Science Amusante, 1890/3 'La Science Amusante' by Tom Tit (real name Arthur Good) was published in three volumes in Paris by Librairie Larousse during the years 1890, 1892 and 1893. Each volume is a collection of articles, mainly of scientific experiments using everyday objects, but also of mathematical novelties, which had been previously published in the French magazine 'L'Illustration'. Some of these articles featured paperfolding and many of the designs / novelties appeared here for the first time, including: Showing that the angles of a triangle sum to 180 degrees

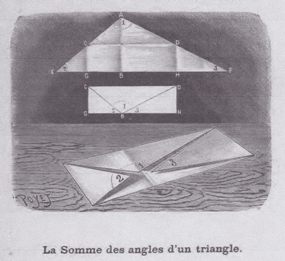

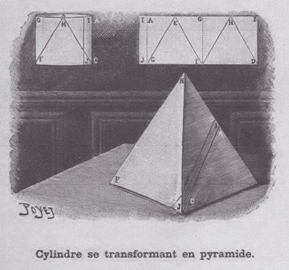

*** Tetrahedron from a Tube

********** Pour Amuser les Petits by Tom Tit, 1894 ********** Le Livre des Amusettes by Toto, 1899 ********** v. In Italian Giuochi Fanciulleschi Siciliani by Giuseppe Pitri, 1883 ********** vi. In Spanish Repertorio Completo de Todos los Juegos, 1896 ********** F: Japonisme and the arrival of Japanese designs in the West After Japan came out of her self-imposed period of isolation in 1853, Japanese design, particularly in the form of prints and ceramics (the one often arriving weapped inthe other), began to have a huge influence in Western Europe, particularly in France, and it became very fashionable to own Japanese objects and mimic Japanese forms and customs. The influence of Japanese design in the West was reinforced by Japan’s participation in the Expositions Universelle held in Paris in 1867 (where there were two Japanese pavilions, one official and one private, funded by the Satsuma family), 1878, 1889 and 1900. ********** We do not know how the Paper Crane became known in the West. It is possible that either it was shown or demonstrated at the 1867 Exposition or that some knowledge of it was gleaned from a woodblock print. However it became known, it was featured on a membership card for a private drinking club in Paris called the Société de Jing-lar that had been formed in 1868 (or possibly 1869) by a small number of enthusiasts for all things Japanese. Three of these membership cards have survived. Unfortunately, we have no idea how the founders of Société de Jing-lar came to know about the Paper Crane or even whether or not they knew how to fold it.

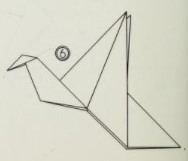

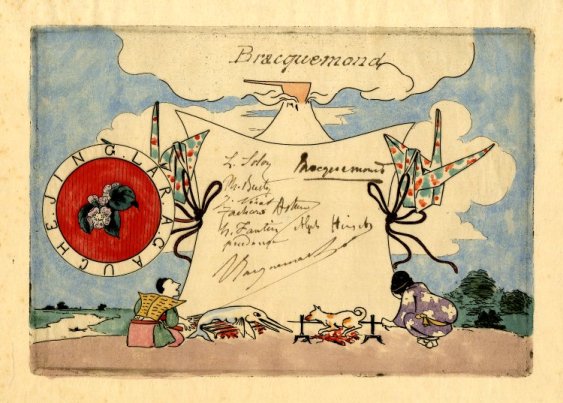

********** ii. The Flapping Bird, 1883 The origin of the Flapping Bird is a mystery and it is not clear whether it's creation was, or was not, a result of the previous arrival of the Paper Crane. On one view, the Flapping Bird is a simplification of the Paper Crane, one which appears if the head and tail (or feet) are not thinned. It is thus easily possible that the basic form of the design could have been arrived at by accident when someone was trying to fold the Paper Crane without being exactly sure how it should be made. It is also possible that, once having arrived at the basic form, the flapping action could be discovered in a similarly accidental way, though not necessarily by the same person at the same time. Alternatively, it is not impossible that yjhe Flapping Bird could have been created from scratch by a European paperfolder. ********** The basic form of the design first appears in a pictorial story by the Catalan illustrator Apeles Mestres which is clearly dated 2nd August 1883. The words below the illustration read, in translation, 'This story was told to me by a swallow that came flying from paper country'. There is no indication that Apeles Mestres knew that the wings would flap if the tail were pulled.

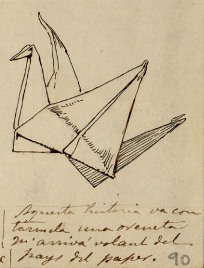

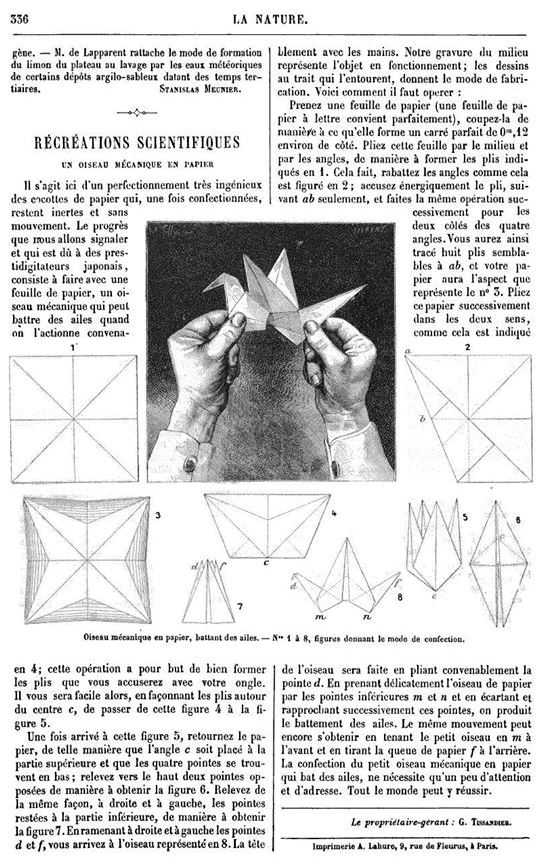

Detail from a pictorial story by Apeles Mestres dated 1883 The design next appears in an anonymous article in Issue 621 of the French magazine La Nature of 25th April 1885, headed 'Recreations Scientifique' and subheaded 'Un Oiseau Mecanigue En Papier' ( a mechanical paper bird). The article includes a wood cut print showing how the bird was to be held in order to make it flap and the information that it originated with 'les prestidigitateurs japonais' (Japanese conjurors).

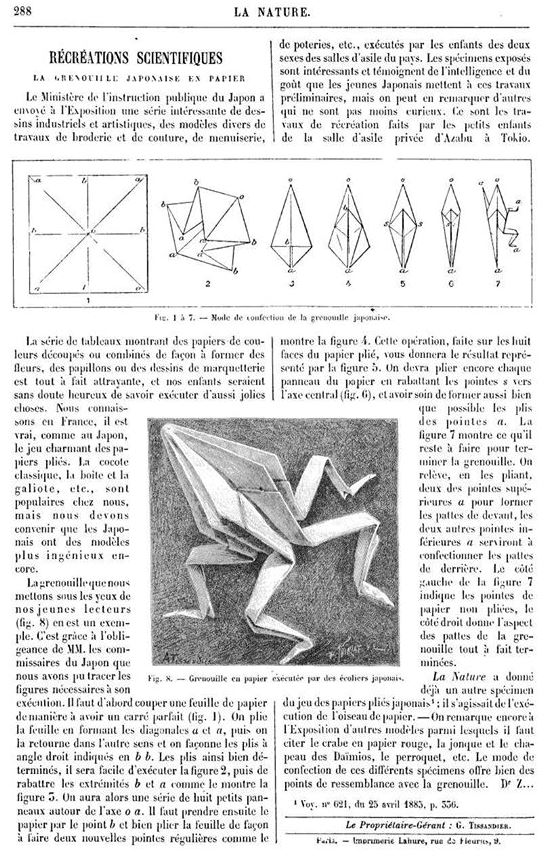

The statement that the Flapping Bird originated with 'les prestidigitateurs japonais', seems suspect to me. If this statement were true it would be very odd that there should be no record of the design in Japan until 1957. Consequently it seems likely that this is an example of the practice, common in the 19th century, of attributing a Chinese or Japanese origin to some novelty or entertainment to enhance it with an air of oriental mystery. ********** iii. The Inflatable Frog, 1889 Japan’s participation in the 1889 Exposition (the event for which the Eiffel Tower was constructed) was particularly important from the point of view of paperfolding history. The magazine La Nature Issue 852 of 28th September 1889 contained an article headed 'Recreation scientifiques' and subheaded 'La grenouille japonaise en papier' (The Japanese Paper Frog) which explains how to make the Blow-up Frog (though the author does not appear to be aware that the frog can be inflated). The article is interesting not only for the diagrams it contains, but also for the incidental information it provides. In his introductory paragraphs the author, Dr Z…, states, roughly, 'The Ministry of Public Education of Japan has sent to the Exhibition an interesting series of industrial and artistic designs ... made by children of both sexes in the country's school rooms ... but one can notice others which are not less curious. These are the recreational works done by the small children of the Azabu private school in Tokyo. The series of displays showing cut out and coloured papers combined to make flowers, butterflies or marquetry designs are quite attractive and our children would probably be happy to know how to make such pretty things. In France, it is true, we also know the charming game of folding paper. The classic Cocotte, the box and the galiote etc., are popular here but we must agree that the Japanese have more ingenious models. The Frog that we put in front of our young readers is an example’, and, ‘We also noticed in the exhibition other designs among which were the crab from red paper, the junk and the hat of Daimios, the parrot etc., The way these designs are made has many points of resemblance to the Frog.' It is difficult to identify the 'crab from red paper', but the' junk' is probably the Takarabune, the 'hat of Daimos' possibly the Kabuto, and the 'parrot' the Paper Crane.

********** iv. The Cut Swallow and Galiote A chapterof 'Revue des arts décoratifs' of 1st January 1900 written by Felix Regamey and titled 'L'enseignement du Dessin dans les E'coles de Files au Japon' contains a picture of the Cut Swallow and says 'In elementary classes, the exercises which lead to the study of the drawing itself are, as in our case, folding, cutting.and gluing ... As an example of folding: a galiote, a bird.' This is the first appearance of this design in the West. The 'galiote' is not pictured and so cannot be identified, although the name is sometimes used for the Chinese Junk.

********** iv. Le Prestidigitateur Alber Between 1899 and 1903 'Le Prestidigitateur Alber', otherwise known as the magician Alber Graves (real name Jean Jacques Édouard Graves), published a series of articles in the French children's magazine 'Mon Journal' which included some Japanese designs. Alber claimed that his source for these designs was a Japanese friend variously named as Mlle Kawala, Mlle Kawada or Madame Kawada, though whether this lady actually existed or was invented as part of his magician's patter is hard to say. If she was invented, then he must have had some other Japanese source. Some of the designs, such as the Paper Crane and the Inflatable Frog were, as we have seen, already known in the West. Others, such as the Iris / Lily, the Palanquin (a version of the Kago), the Crab and the Kabuto had not appeared in print in the West before. One, Le Kiosque Japonais, is assigned a Japanese origin, but is not evidenced from Japan. ********** G: The Pajarita (again) i. Appearance in 'La Flaca', 1873 We have already seen that the Cocotte design was introduced to Spain from France in the book 'Juegos de los Ninos' by Elisabeth Celnart in 1847. Somewhat surprisingly, in light of its latter popularity in Spain, there is no further record of the design in Spain until 1873, when it features in a cartoon in the satirical magazine 'La Flaca', which was published in Barcelona.

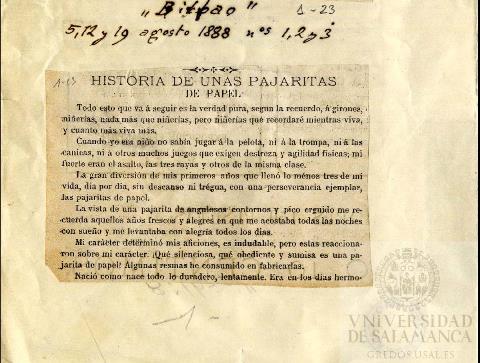

********** ii. Historia de Unas Pajaritas de Papel, 1888 Miguel de Unamuno, born in 1864 and died in 1936, was a Spanish academic, author and thinker who was also influential in the development of paperfolding in Spain and beyond. In 1888 he published an account, 'Historia de Unas Pajaritas de Papel', of how, when he was 10 years old, he and his cousin folded and played with paper Pajaritas and other toys during the bombing of Bilbao during the Third Carlist War.

********** iii. Pajaritologia, 1894 'Pajaritologia', by Senesio Delgado, is an article published in the Spanish satirical magazine 'Madrid Comico' (of which Senesio Delgado was the Director) on 13th January 1894. The article uses the folding of Cocottes / Pajaritas to make satirical points about art and contemporary thought. It is possible that the article inspired or influenced Miguel de Unamuno in the writing of his much more famous 'Apuntes para un tratado de cocotologia', and its existence also perhaps explains why Miguel de Unamuno chose to use the word 'cocotologia' rather than the more obvious 'pajaritologia' in his own work. There is, however, no direct evidence that Miguel de Unamuno was aware of the earlier work. ********** iv. The Most Perfect Paper Paharita Known, 1902 1n 1902 the Argentinean magazine ‘Caras y Caretas’ published a letter from Miguel de Unamuno which was illustrated by a picture of what he called the 'most perfect paper pajarita known', 'although, to be sure, starting out from other figures'. The design is developed from a bird base and appears to be an early version of his Avechucho, made with a simpler head and beak than later versions. We do not know with certainty what the 'other figures' it was derived from were, but, the obvious candidates are either the Paper Crane or the Flapping Bird.

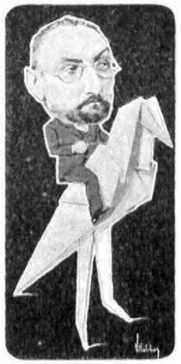

Unamuno amd his 'most perfect paper pajarita known' ********** In April of the same year Unamuno’s second novel 'Amor y pedagogía' was published. The original manuscript for this novel was shorter than the publisher required so it was lengthened by the addition of a foreword, an epilogue and a treatise on the Cocotte / Pajarita design titled 'Apuntes para un tratado de cocotología'. This treatise was attributed to Don Fulgencio, one of the main characters in the story. Much of it seems to be deliberately obscure. (This treatise may have been inspired by the article 'Pajaritologia', by Senesio Delgado, which had been published in 1894. It is possible that Unamuno called his paperfolding ‘cocotologia’ because the more obvious, more Spanish, term, ‘pajaritalogia’ had already been used.) Unamuno went on to devise a number of other designs from the bird base, including several other birds, a seal, a teapot and an Empire style table.

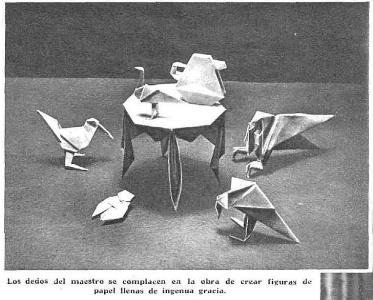

Photograph from Estampa showing a few of Unamuno's designs He remained a passionate recreational paperfolder until his death in 1936 and his design work and love of folding paper inspired the Spanish / Argentinean paperfolding tradition. ********** I: Recreational paperfolding in books and magazines - 1900 to 1955 ********** i. In England and the USA Popular Mechanics magazine, 1917 A design for 'A Model Paper Monoplane that can be Steered' (now better known as 'The Swallow') was published in the November 1917 issue of Popular Mechanics magazine.

********** The Magic of Science by A Frederick Collins, 1917 Another design for a 'Paper Glider' (now better known as 'The Cut and Fold Model Aeroplane'), in which the front of the wings are folded over and over to add weight at the front of the design, was published by in 'The Magic of Science' by A Frederick Collins in the same year.

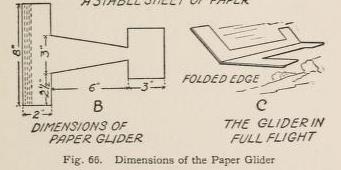

********** 'Paper Magic' by Will Blyth, 1920 Will Blyth was British, a professional conjuror and a member of the Magic Circle. His Foreword makes it clear, however, that this book is aimed at a general readersjhip rather than at his fellow conjurors. The paperfolding content consists of already well-known classic paperfolds and fold and cut designs, though some are interpreted in original ways. ********** 'More Paper Magic' by Will Blyth, 1923 This follow-up to 'Paper Magic' contains a varied mix of paperfolds, some classic and some new, napkin folds and fold and cut designs, which Will Blyth appears to have collected after the publication of his first book. The stand out design is the 'Paper Snapper' (the cut version), which appears here for the first time in the literature.

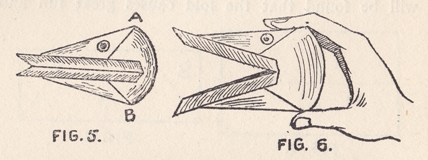

********** ‘Fun with Paper Folding’ by William D Murray and Francis J Rigney, 1928 Both authors were American conjurors, although whether they were professional or amateur I do not know. William D Murray wrote the book and Francis J Rigney drew the illustrations. The Foreword says that the book is aimed at children. The book contains a variety of simple paperfolds, nost of which are classic designs, but some of which are new. Some of these may be William D Murray's own creations. Others were possibly collected during his travels in China, which he mentions twice in the Foreword. As far as I know, for instance, diagrams for the 'Pagoda' had not been published in the West before.

This book was highly influential. Jack J Skillman famously began paperfolding when he and his brothers purchased a copy of this book in 1929 and Lillian Oppenheimer learned much of her paperfolding from it. It was republished as 'Paperfolding for Beginners' by Dover publications in 1960, and, as far as I know, remains in print. ********** 'Winter Nights Entertainments' by R M Abraham, 1932 R M Abraham was British. This book, as the title clearly suggests, is a book of entertainments for children intended to help pass the long winter's nights. It contains a chapter devoted to paperfolding. Much of the content is the same as the earlier books by Will Blyth, but there is some addirional material. The paperfolding novelty known as the 'Sugar Tongs', for instance, appears here for the first time in the literature.

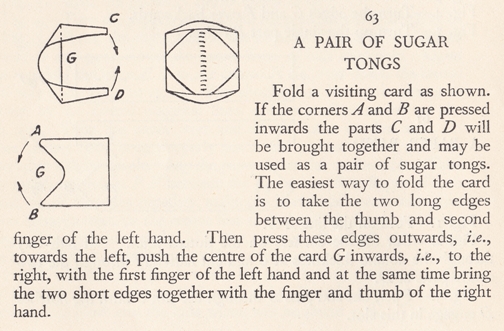

********** 'Diversions and Pastimes' by R M Abraham, 1933 Ths book is a follow-up to 'Winter Nights Entertainment' and has much the same purpose. There is no chapter specifically devoted to paperfolding. However, it contains a scatter of paperfdolding items, including 'Troublewit'. The highlight is probably this mathematical puzzle, which as far as I know, had not appeared in print before.

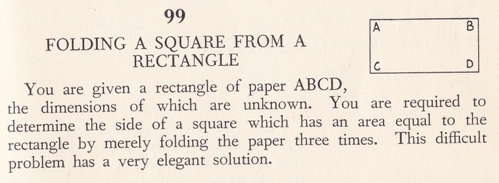

********** 'Paper Toy Making' by Margaret Campbell, 1937 Margaret Campbell was South African. In her Introduction she states: 'This book was written for my grandchildren only, without any idea of ever publishing it'. She also says that: 'I learned much of my paper-folding in Japan. China, and other Eastern countries'. In his Preface, her nephew, Roy Campbell, says: 'Though she includes many of the traditional tricks, a great many more of these paper structures are of her own invention.' Unfortunately the text of the book does not clarify which designs fall into these various categories. Roy Campbell's Preface is also noteworthy for his statement: 'I can quite imagine that the traditional flying bird might have been one of the lighter butterfly-fancies of Leonardo's brain' thus introducing to paperfolding history a fallacy which has proved hard to kill. The book contains a mixture of Froebelian folds of life, fold and cut designs and well known standards such as the Flapping Bird, but also contains some previously unknown material, some of which may be the author's own invention. The book is also noteworthy for the quality of the illustrations and the way the later designs in the book are grouped by reference to their 'foundation' folds. This book is credited with awakening an interest in recreational paperfolding in Robert Harbin in 1953 (see below). ********** 'At Home Tonight' by Herbert McKay, 1940 Herbert Mckay was British and the author of many books on many subjects, but especially about science and mathematics. 'At Home Tonight', published by Oxford University Press, in 1940, is a compendium of parlour games, puzzles, simple science experiments, riddles and paperfolding. Although many of the puzzles are by no means simple the illustrations show that it was aimed at children. Very bright children, perhaps. The book contains a chapter on 'Paper-folding', another on 'Geometry by Paper-folding' and there is other paperfolding material scattered elsewhere in the book. Many of the designs are well-known classics, but others, particularly the paper hat and boat variants, appear to be new and may well be designs created by the author. ********** Paperfolding in the Rupert Annuals, 1946 onwards In 1946 the British illustrator Alfred Bestall, who wrote and drew a cartoon strip featuring Rupert Bear for the Daily Express, wrote a story for the Annual featuring the Flapping Bird. The Annual also included diagrams for folding the design. Thereafter, origami became a regular feature of the Annual until 1988, sometimes featuring classic designs, sometimes designs by Alfred Bestall himself, or by other contemporary paperfolding designers.

********** 'The Art of Chinese Paperfolding' by Maying Soong, 1948 According to David Lister (see his article Origami from China) Maying Soong was a member of a prominent Chinese banking family, and a sister-in-law of the Chinese nationalist leader, Chang Kai Chek (though I have not been able to substantiate this relationship). She was brought up in China but moved to live in the United States in the 1940s, after the Communist takeover and her book was written in English for publication in the USA. The book contains designs that the author claims are of Chinese origin, and although it is probably true that she learned them in China in her childhood, many of them are originally Western or Japanese designs. There are, however, a number of designs that are most probably genuinely Chinese in origin, including the 'Pagoda', the 'Chrysanthemum Box', 'the 'Armchair and Settee' and the 'Table.' The 'Table' is not known from any other source.

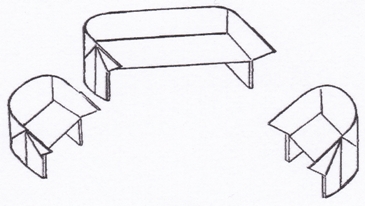

********** ii. In France Mes Jolie Jeux by Henriette Suzanne Bres, 1900 ********** La Recreation en Famille by Tom Tit, 1903 ********** Les Bon Jeudis by Tom Tit, 1906 ********** 'Les Petits Secrets Amusants' by Alber-Graves, 1908 This book brought together the designs that 'Le Prestidigitateur Alber' had previously published in his articles in the children's magazine 'Mon Journal' (see above) and made them available to a wider audience. Many subsequently become established in the Western European recreational paperfolding repertoire. Many of the same designs were also republished in the journal 'La Nature' in the early 1930s. ********** Distractions Enfantines by Marie Koenig, 1910 ********** Joujoux en Papier by Tom Tit, 1924 ********** Jeux de pliages by Ferdinand Krch / Cuori / Coeur, 1933 ********** Au Pays des Mains Agiles, 1949 ********** Occupons Nos Doigts by Raymond Richard, 1950 ********** iii. In Germany Grosses Illustriertes Spielbuch fur Knaben by Dr Jan Daniel Georgens, 1900 ********** Handbuchlein der Papierfaltekunst by Joseph Sperl, 1904 ********** Häusliche Kleinkunst und Bastelarbeit in Wort und Bild by Hermann Pfeiffer, 1911 ********** Allerlei Papierarbeiten by Hilde Wulff and Carola Babick, 1936 ********** J: The Lover's Knot, 1913 Vol 5: Issue 2 of 'The Origamian' for Summer 1965 included an article by Fred Rohm, 'On Bases', which mentions that he remembers learning the 'Lover's Knot' from his Aunt Mary, who called it a 'German Bow Knot' when he was six years old. Since he was born in 1907 that would make the year in question 1913. If this recollection is correct, this is the earliest known evidence for the existence of this paperfold. The next earliest evidence of the 'Lover's Knot' dates from 1934, when the design was patented as a puzzle

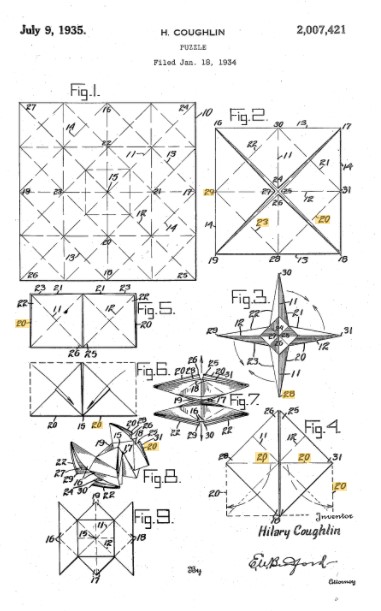

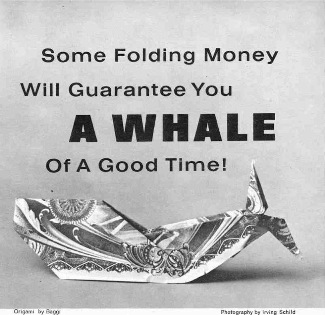

********** K: The Conjuring Connection / Dollar Bill Folding We have already seen that paperfolding and conjuring have connections that go back many years. The 'Buddha Papers' magical trick can be traced back to 1584 and 'Troublewit' to 1676. In more modern times, Le Prestidigitateur Alber (aka Alber-Graves) published a series of articles in the French children's magazine 'Mon Journal' between 1899 and 1903. These articles were subsequently combined into a book, 'Les Petits Secrets Amusants', published in 1908. Following the example set by Alber-Graves, other conjurors seized the commercial opportunity to write books of recreational paperfolding, primarily aimed at children (see above). Paperfolding and conjuring, it seems, were highly compatible interests, perhaps because folding a flapping bird, for instance, out of a sheet of paper is somewhat similar to producing a rabbit from a hat, and, during the course of the early and mid twentieth century, many conjurors interested themselves in paperfolding both as a hobby and as a part of their professional activity, particularly in the folding of designs from dollar bills. ********** 'Paper Tricks' by Will Goldston, 1919 Will Goldston was a well-known conjuror in his day, a prolific author of books about various aspects of conjuring, owner of a magic shop in London, and an agent for many other conjurors. I have not seen a full copy of 'Paper Tricks' but those pages that I have seen show that many, though not all, the tricks involved some element of paperfolding. ********** 'Houdini's Paper Magic', 1922 Houdini's Paper Magic' was published by E P Dutton and Company of New York in 1922. According to a note in Gershon Legman's 'Bibliography of Paperfolding', it is said to have been ghost written by Walter B Gibson, another conjuror. There is no Foreword and consequently no explanation of whom the book is aimed at. The style suggests that it is aimed primarily at fellow conjurors but the fact it was published by E P Dutton suggests otherwise. Perhaps Houdini's name persuaded them that it would have wider appeal. Most of the designs in the book are pretty standard fare. On several occasions the author says that he learned the design from a Japanese friend. The book does contain one Japanese design, the 'Hexagonal Tamatebako' which had not been previously published in the West, although this is not one of the designs said to have been learned from his Japanese friend.

********** Dollar Bill Rings In his Preface to 'The Best of Origami: New Models by Contemporary Folders' by Samuel Randlett, which was published in 1963, Martin Gardner reminisces about attending a magic convention in Chicago in the 1930s at which almost every other attendee was wearing a ring folded from a dollar bill:

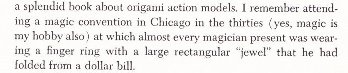

The particular design of ring in question has never been established (but see 'Bill-Folds' by Al O'Hagan, 1945 below). ********** Designs in 'The Jinx', 1940 Two designs for folds from dollar bills were published in the magic magazine 'The Jinx' in 1940. The first was a design called 'Bow Knot Money' (an adaptation by Mitchell Dyszel of the Lover's Knot from a dollar bill which places Washington's face in the knot)

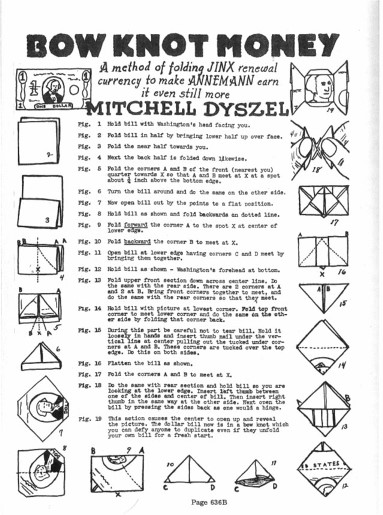

********** and the second 'Double Dollar', an effect by Jack Vosburgh in which a dollar bill is folded so that it looks like two bills, then is shown to have become two separate bills.. ********** 'After The Dessert' by Martin Gardner, 1941 After the Dessert' was written by Martin Gardner, who was an amateur magician, and was published by Max Holden in the USA in 1941. According to the author's Introduction it was written 'for the performer, professional or amateur'. It contains a number of paper / napkin folding items intended to be suitable for after dinner entertainment, including the Flapping Bird. ********** 'Bill-Folds' by Al O'Hagan, 1945 'Bill Folds' by Al O'Hagan was a 6-page leaflet issued by George Snyder's Magic Shop of Cleveland, Ohio in 1945. Inter alia it includes three noteworthy designs folded from dollar bills, a Bow-Tie (with Washington's face in the knot), a Picture Frame (with Washington's face in the centre) and a signet Ring (with the letter 1 featured on the stone). It is possible, though not confirmable, that this is the dollar bill ring remembered by Martin Gardner from a magic convention in Chicago in the 1930s (see above). ********** Article by Gershon Legman in Phoenix magazine, 1952 'The Phoenix' issue 251 of March 21st 1952 contained two folds by Gershon Legman. The 'Lotus' is a version of the Lover's Knot (but folded from a blintzed square) which can be opened up by pulling on the top and bottom points. The Bow-Tie is folded from a dollar bill and said to be simpler than those previously published in the literature. ********** L: Paperfolding in education - 1900 to 1970 ********** The decline of Falten / The rise of Paper Sloyd During the early part of the 20th century interest in Froebel's classic paperfolding based occupations began to decline, though at a different rate in different countries. It had, of course, never been particularly influential in France, where, as we have seen, paperfolding was seen more as a way of promoting manual dexterity rather than intellectual development or creativity. In England and the USA, Froebelian-style paperfolding began to be replaced in the kindergarten and primary school syllabuses by Paper Sloyd, which was a type of cardboard modelling where simple, useful, objects, such as boxes, were made from templates, the process being to cut out the basic shape from the template, fold it up and glue it together. This type of handicraft was much more easily accessible for pupils, but, equally, of much less educational value. ********** M: Paperfolding as a means of Education in Art and Design In 1922 Josef Albers was appointed as a Vorkurs (introductory course) instructor at the Bauhaus and, among other things, began to encourage his students to explore how structures could be created using paperfolding.

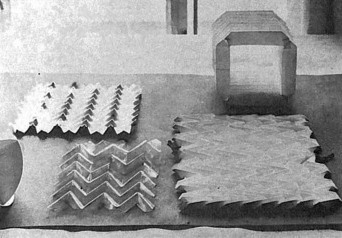

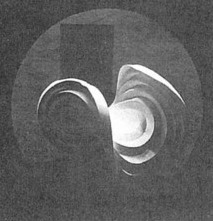

Among the designs which appear to have been originated at this time were the Zigzag Corrugation, the Hyperbolic Parabaloid and the Saddle.

In 1932 the Bauhaus closed and Albers emigrated to the USA where he taught a similar course at Black Mountain College until 1949. ********** O: Spanish and Argentinean Paperfolding after Unamuno Miguel de Unamuno (1864 to 1936) became famous for his love of paperfolding and, although direct connections are difficult to find, it seems as though his well-advertised passion for recreational paperfolding made it a culturally acceptable practice among other members of the intellectual class. This was, of course, the time of the Spanish Civil War (1936/9) and, because of their opposition to the Nationalists. many of these intellectuals were forced, or chose, to go into exile, mainly to Argentina and Mexico. Some of these exiles were paperfolders. Equally, other paperfolders remained in Spain. Between them they developed a tradition of paperfolding creativity based, mainly, though not exclusively, on the bird base and variations of it. Although Unamuno himself famously eschewed the use of cuts, the paperfolders who came after him in the Spanish tradition seem largely to have been comfortable with using cuts to create extra structural points and to add details to their designs. i. Natividad Sanchez Ferrero As a child, Natividad Sanchez Ferrero, lived in Salamanca and was friendly with some of Miguel de Unamuno's children. Later, when she was a nun living in Morocco, she designed two famous figures, the Moor at Prayer and the Moor at the Fireside, which were later to be published in Robert Harbin's books. The date she designed the figures is not known. However, we know it was during Miguel de Unamuno's lifetime since he kept a copy of the Moor at Prayer figure in his wallet.

Illustration of the 'Moor at Prayer' taken from Robert Harbin's 'Paper Magic' ********** ii. Vincente Solorzano Sagredo (1883 to 1970) Vicente Solorzano Sagredo was born on 24th July 1883 in Burgos in Spain. He gained a degree in medicine in Madrid in 1908, and, it is said, thereafter became a ship's doctor. After traveling widely, Solorzano settled down to live in Argentina and retrained in dentistry. He then opened a dental practice in Buenos Aires. I am not aware of any political reason or necessity for his leaving Spain. We do not know where or when he began paperfolding, but by the time an article about his paperfolding designs, titled 'Las Papirolas del Doctor Solorzano' was published in 'La Prensa' in 1936, he had already developed his system of 'deltoides', or bases, and used them to create a diverse range of designs. The article mentions 'Birds of diverse families, anthropoids, reptiles, bats, marsupials, horses' among others. The Buenos Aires edition of the magazine 'Caras y Caretas' of 15th November 1938 also carried an article about his paperfolding, from which the following illustration showing the range of designs he had already developed at this stage is taken.

In contrast to Unamuno, Solorzano was completely at ease with using cuts to enable him to create designs with the necessary number of legs, ears, antennae and other appendages. A profile of Dr Solorzano in:Vol 5: Issue 3 of 'The Origamian' for Autumn 1965 sets out his views on curtting in some detail. For instance, he says, 'slits and short cuts in folds constitute an advance and prove useful in making better models.' Whether these models were 'better' or not is open to some question, but they undoubtedly enabled Solorzano to model living creatures such as insects and crustaceans in more realistic ways, designs that would, at the time, have been out of reach without the use of cuts. However, despite this, or perhaps because of it, Solorzano's best known design, remains his simple Pavo Real / Peacock, which, in the form shown below, is made without cuts of any kind.. In other versions a cut is used to create a crest.

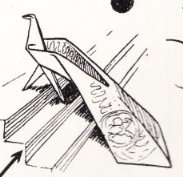

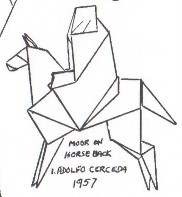

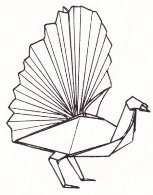

Illustration from 'Paper Magic' by Robert Harbin, which was published by Oldbourne in London in 1956 Solorzano was fond of coining new words and expressions. Among many others, he coined the term 'papiroflexia' to mean 'paperfolding', since there was no other suitable word in Spanish. He also coined 'papirolas' to mean 'paperfolds', although this has not caught on in the same way. Solorzano wrote many books about paperfolding, although because he was not a competent illustrator (in the La Prensa article referred to above he admits he is pretty clumsy at drawing) most of the illustrations are annotated photographs. Perhaps also for this reason most of the books concentrate on simpler, mostly traditional, designs, rather than his more complex works. In 1962 , however, he published his magnum opus 'Papiroflexia Zoomorphica', in two volumes, which explained many of his complex designs and the methods he used to produce them. The 1700 or so illustrations for these works were drawn by Ligia Montoya, although her efforts in doing this are not acknowledged in the work. This work included designs made from oblongs, right angle isosceles triangles and other convex polygonal shapes, as well as some compound designs. A profile of Ligia Montoya, written by Gershon Legman, in Vol 8: Issues 1 and 2 of 'The Origamian' for Spring and Summer 1968, claimed that Solorzano had also included some of Ligia Montoya's own designs for birds (though which ones these were we do not know, since Montoya did not specify this), some of Legman's own designs (a dog, a fox and a wolf), and those of unnamed others, in the book, without acknowledging their authorship. Solorzano subsequently disputed (at least parts of) this claim. Full details of the article and subsequent correspondence in the pages of 'The Origamian' can be found here. ********** iii. Dr Nemesio Montero Dr Nemesio Montero is the author of 'El Mundo de Papel', which was published in Valladolid in 1939. The titles of a number of designs in the book are marked with asterisks, which is said to denote that they are original designs of the author and his sister Esperanza. However, some of these attributions are questionable. The book contains the first mention of / diagrams for two famous designs, El elepante (the Spanish Elephant) and 'El borriquillo con aguaderas' (the Donkey with Panniers), both of which are heavily, and multiply, cut. The Spanish Elephant is not marked with an asterisk but the Donkey with Panniers is.

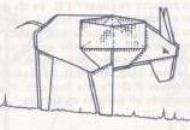

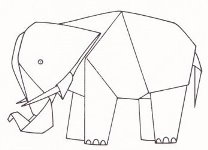

********** iv. Giordano Lareo Giordano Lareo is the author of 'Papiro-Zoo: Manual practico de cocotologia o papirologia', which was published in Buenos Aires in 1941. I have not seen a copy of this book but here is what Gershon Legman said about it in his Bibliography of Paper Folding.

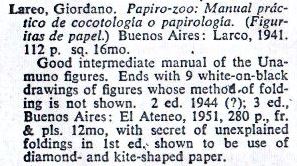

********** v. Elias Gutierrez Gil 'Elias Gutierrez Gil is the author of 'Papiroflexia', which was self-pubished in 1951. A number of designs in the book are traditional, but most are the work of the author himself. The introduction acknowledges a debt to Miguel de Unamuno, roughly translated, (paperfolding is) 'an inconsequential thing, which, however, was one of the most characteristic hobbies of a figure of such rare originality as Miguel de Unamuno. The name he gave to this activity is the one that gives title to our volume, Cocotology or Papiroflexia.' Many of the designs included in the work are cut. Some are developed from the Bird Base folded from the square, but others are developed from versions of the same base folded from a rhombus or a four-pointed star. There are also two 3-part compound designs.

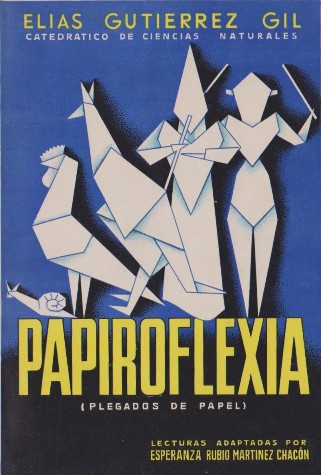

********** vi. Lorenzo Herrero Sainz (1913 to1997) Lorenzo Herrero Sainz was born in Burgos in 1913. He created his first original design, a 'lawyer's hat' in 1924 after learning how to construct an equilateral triangle by folding at school. He fought in the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) and created some original figures from the pamphlets dropped from planes by the other side. After the war, the need for money to survive the harsh post-war years made him conceive of creating a book of paperfolding designs. He proposed the book to several children's newspapers and other publishers until finally it was accepted for publication by Editorial Salvatella in Barcelona, but only on condition that it was published anonymously. It appeared in 1952 under the title 'Una Hoja de Papel'. The contents include many designs by the author, most of which are either cut or compound or both as well as some 'traditional' designs such as the 'Cestito' shown below.

********** vii. Ligia Montoya (1920 to 1967) Ligia Montoya was born in Buenos Aires in 1920, but moved to Spain with her family and completed her high school education there. She first learned paperfolding from a Spanish cousin during this period. Following the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936, and the subsequent closing of the universities in Spain, she returned to Argentina, and studied librarianship at the Universidad de Buenos Aires, subsequently becoming the Director of the library of the faculty of Philosophy and Letters. A profile of Montoya, written by Gershon Legman, and published in 'The Origamian' for Spring and Summer 1968, tells how Legman first came to know of her. Thereafter they corresponded regularly until her death, and Legman encouraged her in her creative activity. *********** At some point, and as far as I am aware we do not know how, and whether this was before or after her first contact with Legman, Montoya also came into contact with Dr Vicente Solorzano Sagredo (see above) and agreed to draw the illustrations for his magnum opus 'Papiroflexia Zoomorphica', although her efforts in doing so are not acknowledged in the work. ********** Legman introduced Montoya to Lillian Oppenheimer (see below) and she became an honorary member of The Origami Center. Many of her designs were published in issues of 'The Origamian' and in books by such authors as Robert Harbin and Samuel Randlett (see below). Her own folding seems to have been done largely using white airmail paper and her designs were characterised by relative simplicity and an artistic touch. She tried to avoid the use of cuts.

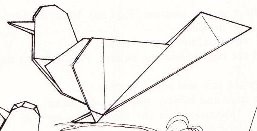

An illustration of one of Montoya's birds from Robert Harbin's 'Secrets of Origami', published in 1964 ********** In 1959 she contributed a number of designs to the 'Plane Geometry and Fancy Figures' exhibition held at the Cooper Union Museum in New York.

********** Montoya is probably now best remembered for her clean-lined bird designs, and for her success in reverse engineering the Kan no mado Dragonfly. ********** viii. Adolfo Cerceda (1923 to 1979) Ismael Adolfo Cerceda was born in Buenos Aires on 13th of April, 1923 and died on 25th July, 1979. He was a professional knife-thrower and magician who worked professionalluy under a number of different names including Don Alvan and Carlos Corda. According to Vicente Palacios, writing in his book 'Fascinante Papiroflexia', which was published in 1984 and includes diagrams for around 100 of Cerceda's designs, Cerceda's interest in paperfolding began when he was 18 (ie in 1941) when he met a man who made figures by cutting paper. In looking for a book about this he found one on paperfolding instead (the title of the book is not specified) and 'began to take a serious interest in paperfolding'. Palacios says that he was influenced by Giordano Lareo's book 'Papirozoo' and several times visited Dr Solorzano Sagredo. However, it seems that unlike Solorzano, Cerceda had the technical ability to create complicated designs without resorting to cuts. He also became aquainted with, and corresponded with, Ligia Montoya. No dates for any of these latter events are given. The earliest design of Cerceda's that we know of is his 'Moor on Horseback', said by Palacios to be the earliest example of a two-subject design, which was published in 'The Origamian' for Spring / Summer 1962 with a title dating it to 1957.

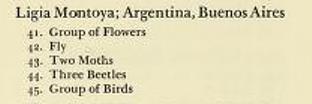

Another early design was his Peacock, from a 2x1 rectangle, which, in a letter published in 'The Origamian' for Autumn 1969, Cerceda says was created in 1958.

At some point in 1959 Cerceda began to correspond with Gershon Legman. Cerceda is not among those made 'honorary members' of 'The Origami Center' by Lillian Oppenheimer in November 1958 but at some point thereafter he was introduced to her, possibly by Legman, and became part of the circle of creators who were 'members' of that organisation. A number of his original designs were published in both 'The Best of Origami' by Samuel Randlett, which was published in 1963, and in 'Secrets of Origami', by Robert Harbin, which was published in 1964. According to Palacios 'in 1969 ... Cerceda made 13 tapes of six minutes each on paperfolding, which were shown on French television with instant success.' ********** P: Flexagons and flexagon-based novelties According to an article titled 'Flexagons', written by Martin Gardner, which was published in issue 195 of Scientific American in Dec 1956, Arthur Stone discovered hexaflexagons, specifically the trihexaflexagon and hexahexaflexagon, in 1939 when playing with inch wide strips of paper. With the help of friends Bryant Tuckerman, Richard Feynman and John Tukey many other hexaflexagons were quickly discovered and analysed. It is possible that some tetraflexagons were also first discovered at this time, although there is some possibility that some forms of tetraflexagon were already known. The Chinese Wallet is, of course, essentially a tetraflexagon. In addition, according to Martin Gardner, writing in an article in the May 1958 issue of 'Scientific American, the tetra-tetraflexagon 'has often been used as an advertising novelty because the difficulty of finding its fourth face makes it a pleasant puzzle. I have seen many such folders, some dating back to the 1930s'. I have not been able to verify this early date, however, an application for a patent for such a three-row tetraflexagon, said to be invented by Stuart Edward Wade and Alexander Moulton, was made in 1941 with patent approval granted for the United States in 1942. According to the same article by Martin Gardner, in 1946 'Roger Montandon ... copyrighted a tetra-tetraflexagon called 'Cherchez la Femme', the puzzle being to find the picture of the young lady.' He does not mention that the novelty was his own design. (This tetrafexagon is also sometimes called the 'Trick Book'.)

One face of a puzzle tetraflexagon design known as 'Cherchez la Femme', courtesy of the Jerry Slocum Mechanical Puzzle Collection. ********** Diagrams for the Printer's Hat (a very different design of paper hat from the Workman's Hat) appeared in Popular Mechanics Magazine for February 1940, an indication that printer's in the USA had probably started wearing this type of paper hat as protective headgear by this date. Printer's Hats continued in use into the 1950s.

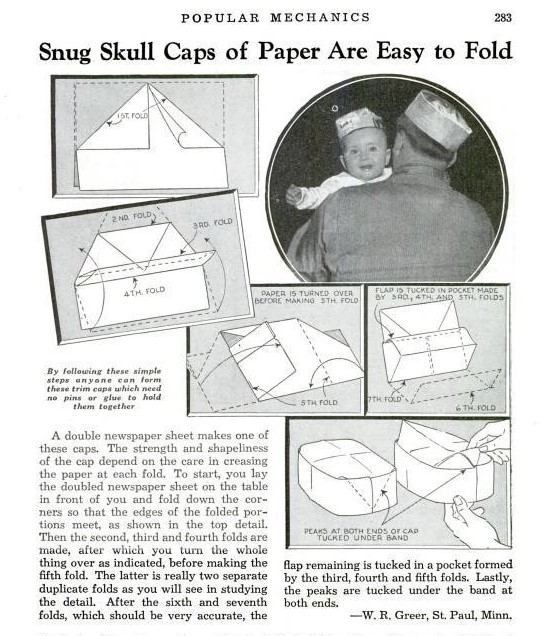

********** R: The Flexatube, 1955 This remarkable flexible paper puzzle is first described in 'The Mathematics Gazette' Vol 39 issue 330 of December 1955.