| The Public Paperfolding History Project

Last updated 10/3/2026 x |

|||||||

| The Flapping Bird | |||||||

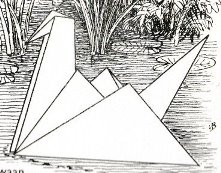

This page is being used to collect information about the history of the paperfolding design known as the Flapping Bird. There are, of course, many other flapping birds in the modern origami repertoire, but this is the only one that we know to be a traditional design. Please contact me if you know any of this information is incorrect or if you have any other information that should be added. Thank you. This page includes entries for a seated variant of the Flapping Bird made by adding additional creases to the wings. ********** Introduction The origin of the Flapping Bird is a mystery. There are three possibilities: Theory 1: The Flapping Bird was originally a Japanese design brought to Europe by Japanese conjurors. This theory is based on the statement in Issue 621 of the French magazine 'La Nature' of 25th April 1885 (see below) that the design originated with 'les prestidigitateurs japonais' (Japanese conjurors). However, there is no evidence from Japan itself that the design was known there until the modern era and it may be that a Japanese origin was imputed by the unknown author of the article to make the design seem more mysterious and attractive, something that we know happened with Troublewit and other paperfolds and magical effects. Further possible evidence of a Japanese origin occurs in 'La Nature' Issue 1093 of 12th May 1894 in an article by 'Dr Z...' which states, roughly, 'We have previously published several recreations that can be made with paper; we gave the way of making a bird, whose wings can be made to move. This invention is Japanese; the Japanese made it known, with great success, at the Exposition of Paris in 1889.' This, at first, seems good evidence, but footnote 1 on the same page makes it clear that the previous publication of the flapping bird referred to was that in 1885, prior to the 1889 Exposition, which brings the accuracy of the whole statement into doubt. This statement bears comparison to a similar statement in relation to the Blow-up Frog in 'La Nature' Issue 852 of 28th September 1889, also in an article authored by 'Dr Z...', which states, roughly, 'The Ministry of Public Education of Japan has sent to the Exhibition (ie presumably the Paris Exposition of 1889) an interesting series of industrial and artistic designs ... showing cut out and coloured papers combined to make flowers, butterflies or marquetry designs ... In France, it is true, we also know the charming game of folding paper. The classic Cocotte, the box and the galiote etc., are popular here but we must agree that the Japanese have more ingenious models. The Frog that we put in front of our young readers is an example.' If the Flapping Bird had been a 'great success' at this Exposition it is somewhat surprising that it is not mentioned here. This theory is also included, with additional detail, in an article by Carlos Alberto Leumann,which was published in 'La Prensa, Diario de Buenos Aires' on 15th November 1936. (See entry for 1936 below.) It is not clear whether this is an imaginative embroidery of the simple statement in the 'La Nature' article or information from some as yet undiscovered independent source. This theory was also gven creedence in a letter Gershon Legman wrote to Robert Harbin, who then quoted it in his introduction to his 1956 book 'Paper Magic'. (See entry for 1956 below.) Theory 2: The Flapping Bird was accidentally created by a European paperfolder while they were trying to remember how to fold an Orizuru or Paper Crane. This might be possible if someone, perhaps, failed to remember the folds that thin the wings of the Paper Crane and then discovered that, because of this error, if the tail were pulled, the wings would flap. Alternatively it is equally possible that a simplified (plumper) version of the Paper Crane might have been discovered by one person, and the fact that the wings flap when the tail is pulled, by another. This theory cannot succeed unless the Paper Crane was known in Western Europe at a sufficiently early date. We do have evidence that the Orizuru or Paper Crane was known in France as early as 1868 or 1869. However, the early evidence consists of images rather than folding instructions, and we do not know whether these images were drawn from folded examples or copied from similar images in Japanese prints or drawings. Theory 3: The Flapping Bird was created from scratch by a European paperfolder. This theory is also clearly possible. However, there is no specific evidence to support it at present. ********** Incidentally in 'Les Petits Secrets Amusants' by Alber-Graves, which was published by Librairie Hachette in Paris in 1908, the author presents diagrams for 'La grue', a version of the Paper Crane, in which he says, roughly, 'If you take the bird from below and gently pull the tip of the tail with little jerks you will see the animal come to life and flap its wings.'

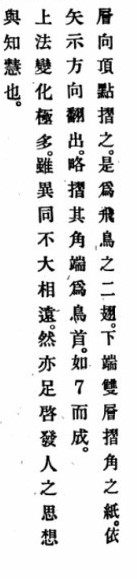

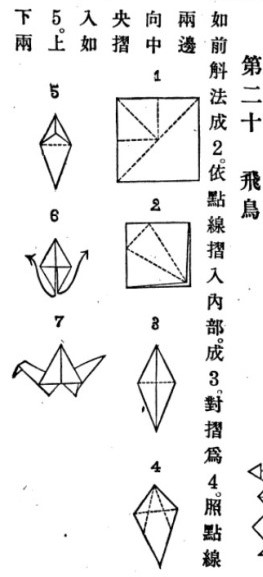

However, this cannot be taken as evidence for a Japanese origin of the Flapping Bird since the design had previously appeared in an article by the same author in the issue of 'Mon Journal' published on 18th October 1902, where the information that the wings would flap if the tail were pulled was not given. It appears, therefore, to be a new discovery of the author at that time. ********** Because of the lack of evidence for the existence of this design in Japan at a sufficiently early date, I believe that Theory 2 is the most likely. It is, however, of course, dangerous to argue from lack of evidence, since evidence to contradict the argument can emerge at any time. ********** In China (and in publications by Chinese authors) 1914 Diagrams for the Flapping Bird appear as 'Flying Bird' in 'Zhe zhi tu shuo' (Illustrated Paperfolding), compiled by Gui Shaolie, which was published by the Commercial Press in Shanghai in Ming guo 3 (1914). However, there is no indication in either the text or the illustrations that the author knew that the wings will flap if the tail is pulled.

********** 1934 The design appears as 'Paper Bird' in 'Zhezhi Xinfa' (New Ways to Fold Paper), which was published by The Commercial Press in China in 1934. The instructions explain how to make the wings flap.

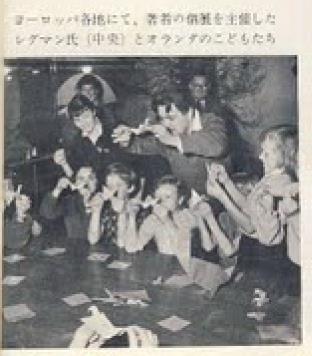

********** In Japan (and in publications by Japanese authors) 1957 A photo of Gershon Legman teaching the Flapping Bird to a group of children at the 1955 exhibition of Akira Yoshizawa's works in Amsterdam and diagrams for several of Yoshizawa's adaptations of the design appear in 'Origami Dokuhon' (aka Origami Dukuhon 1) by Akira Yoshizawa, which was published by Ryokuchi-Sha in 1957.

********** 1959 The Flapping Bird appears, as 'Flying Bird', in 'Fun-time Paper Folding' by Elinor Tripato Massoglio, which was published by Childrens Press in Chicago in 1959. Although many of the designs in the book are ultimately of European origin, it appears that the author learned them in Japan. Jon Silvermoon, one of the author's sons, has kindly confirmed that this applies to the Flapping Bird, which is largely otherwise unknown from Japanese publications at this time.

(This entry is also made in the Western Europe / The USA section of this page) ********* 1966 The Flapping Bird appears at 03:33 in Origami: The Folding Papers of Japan, a film made by the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 1966. ********** 1967 As 'Flying Bird' in 'Origami Festival' by Isao Honda, which was published by Japan Publications Inc in Tokyo in 1967.

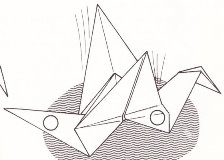

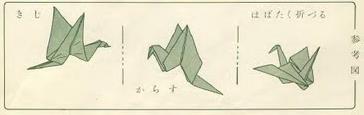

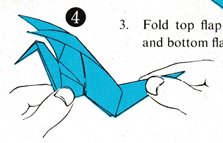

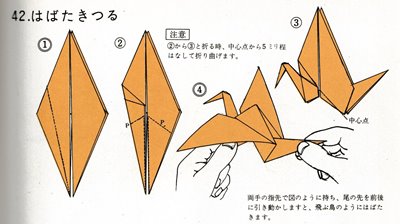

********** 1970 Two simple variants of the Flapping Bird appear in 'Origami Nippon' by Isao Honda, which is a paperback book published by Honda Origami Studio in Tokyo in 1970. Flapping Crane - This design is the Flapping Bird with the neck thinned.

*** Flapping Dove - This design is the Flapping Bird with the tail thinned. This design is attributed to Toshio Chino.

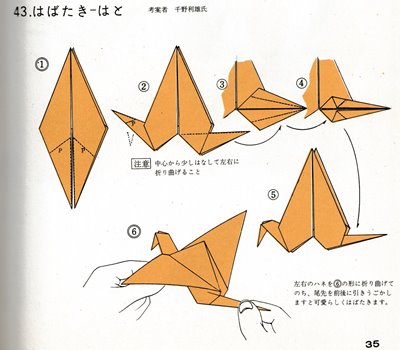

********** In Western Europe and the Americas 1883 The earliest known illustration of the Flapping Bird appears in a pictorial story by Apeles Mestres to be found in his Llibre Verd III notebook. (Information from Coral Roma). The drawing is clearly dated 2nd August 1883. The words below the picture of the flapping bird read, 'This story was told to me by a swallow that came flying from paper country.' (Translation from Juan Gimeno.) This source makes no mention of the flapping action and it is therefore possible that this attribute of the design was not known to Apeles Mestres.

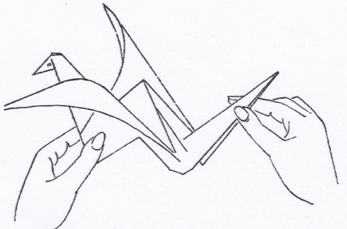

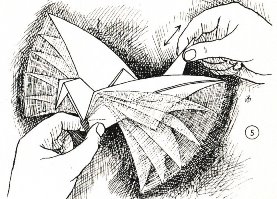

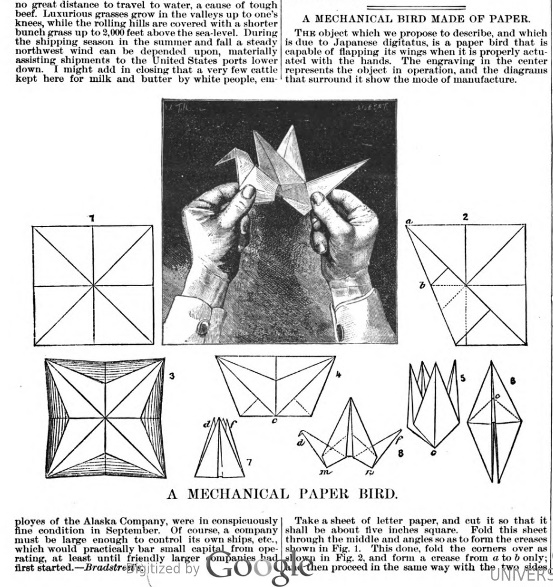

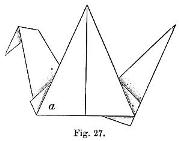

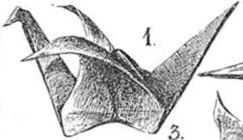

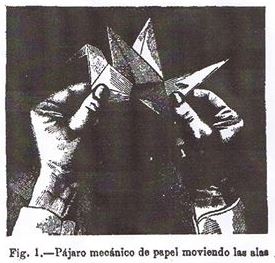

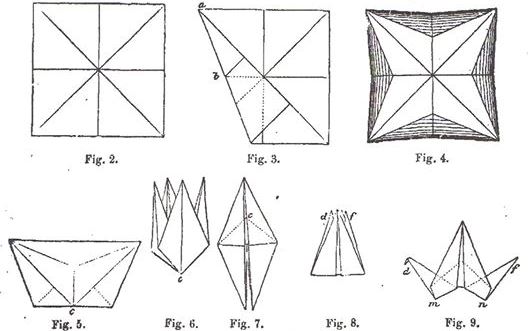

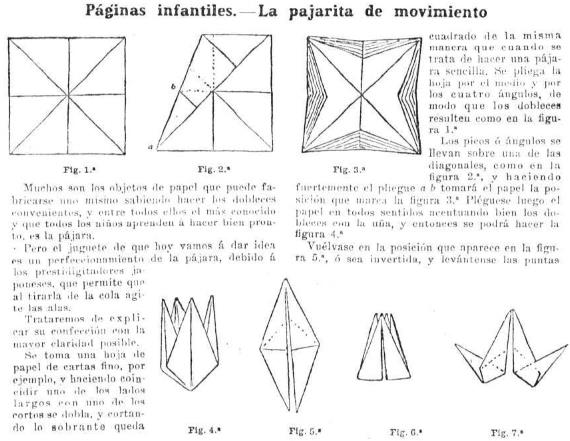

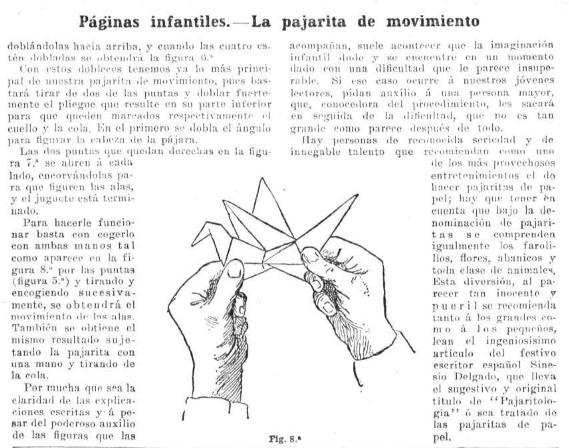

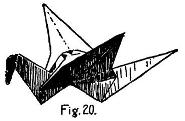

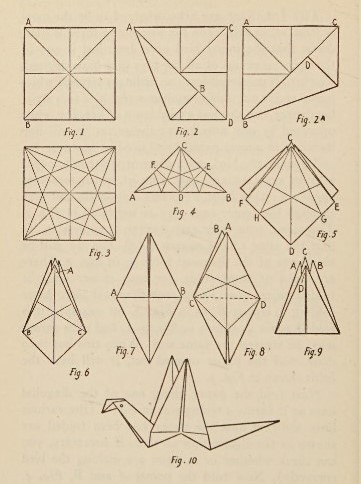

********** 1885 The earliest known diagrams for the flapping bird appear on page 336 of issue 621 of the French magazine 'La Nature' of 25th April 1885, in an article headed 'Recreations Scientifique' and subheaded 'Un Oiseau Mecanigue En Papier' (mechanical paper bird). No author's name is attached to this article. The article includes a wood cut print showing how the bird was to be held in order to make it flap and the information that it originated with 'les prestidigitateurs japonais' (Japanese conjurors). Source: Article by Christophe Curat and Michel Grand in Le Pli 131 of November 2013. English translations of the article appear in British Origami 286 of June 2014 and The Paper 116 of Summer 2014.

The diagrams and the engraving were quickly republished in other countries. The information that the Flapping Bird originated with Japanese conjurors is intriguing. However, there is no direct historical evidence to support this statement it and it may be that a Japanese origin was simply imputed to make the design seem more mysterious, as happened with Troublewit and other paperfolding designs. ********** The Flapping Bird appeared in the USA as 'A Mechanical Bird Made of Paper' on p. 7921 of Scientific American, supplement no 486 of July 4, 1885.

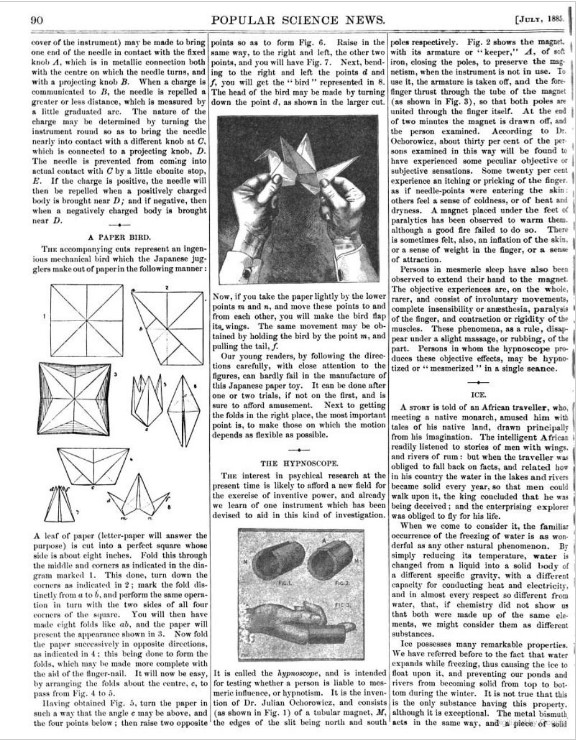

********** A similar article was published in Boston in the July 1885 issue of 'The Popular Science News' under the heading 'A Paper Bird'.

********** 1886 Diagrams were also published in England on pages 618 and 619 of 'The Boy's Own Paper' of June 26th 1886.

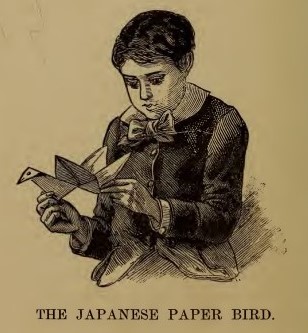

********** 1887 As 'The Japanese Paper Bird' in 'How? Or Spare Hours Made Profitable for Boys and Girls' by Kennedy Holbrook, which was published by Worthington Co in New York in 1887.

********** 1888 The material from 'La Nature' also appeared in the 1888 5th Edition of Gaston Tissandier's 'Les Recreations Scientifiques'.

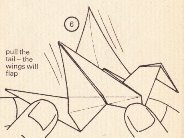

********** According to his book 'Recollections of Tolstoy', as quoted in the Dictionary of National Biography, Aylmer Maude met the Russian writer LeoTolstoy in 1888, having been introduced to him by Peter Alekseyev, who was married to Maude's sister Lucy. Thereafter 'Maude was a frequent visitor, an admirer and friend, playing tennis and chess, enjoying long discussions, but not always agreeing with the great writer 30 years his senior. Tolstoy made return visits, getting to know Louise and the family, even showing the boys how to make "paper cockerels".' (Information from Wikipedia.) In their article 'Leo Tolstoy and the Art of Origami' in British Origami 186 of October 1997, Misha Litvinov and Sergei Mamin mention another incident, this time from 1896, recorded by F D Polenov in his book 'At the Foothills of the Rainbow', Moscow, 1987, in which the writer, then ten years old, happened to be travelling in the same railway carriage as Leo Tolstoy. He records that 'He (Tolstoy) took a piece of paper and began doing something to it. What came out was a bird which flapped its wings when you pulled at its tail.'. In the same article the authors quote, presumably in translation, from the first draft of Tolstoy's essay 'What is Art?' (Leo Tolstoy - The Complete Works, v.30, Moscow, 1951), 'This winter a lady of my acquaintance taught me how to make cockerels by folding and inverting paper in a certain way, so that when you pull them by their tails they flap their wings. This invention comes from Japan. Since then I have been in the habit of making these cockerels for children.' And not only for children , it would seem. The pianist Alexander Gol'denveizer recorded another episode, again from 1896, in his memoir Vblizi Tolstogo / Talks with Tolstoi, translated by S. S. Koteliansky and Virginia Woolf in 1923. 'Once I met Lev Nikolaevich in the street. He again asked me to walk with him. We were somewhere near the Novinsky Boulevard, and Lev Nikolaevich suggested we should take the tram. We sat down and took our tickets. Lev Nikolaevich asked me: "Can you make a Japanese cockerel?" "No." "Look." Tolstoy took his ticket and very skillfully made it into a rather elaborate cockerel, which, when you pulled its tail, fluttered its wings.An inspector entered the car and began checking the tickets. Lev Nikolaevich, with a smile, held out the cockerel to him and pulled its tail. The cockerel fluttered its wings. But the inspector, with the stern expression of a business man who has no time for trifling, took the cockerel, unfolded it, looked at the number, and tore it up. Lev Nikolaevich looked at me and said: "Now our little cockerel is gone..." There is an apparent discrepancy in the dates between the sources here but it is not a significant one since both 1888 and 1896 are after the La Nature publication, and thus there is no need to posit an alternative source. It is quite conceivable that Tolstoy's female acquaintance's knowledge of the design was derived from the La Nature article. But what were Tolstoy's paper cockerels? Litvinov and Mamin mention that several paper birds are carefully preserved under glass in the museum devoted to the work of the painter Vasily Polenov (father of the ten year old boy mentioned above) near Tula in Russia. There are four of these paper birds in the museum and they are indeed Flapping Birds of the traditional kind, three quite well folded and one that is less well folded and looks indeed as though it could quite possibly be the work of a 10 year old boy who might never have folded paper before. I have not seen the birds themselves but I have seen a photograph of them kindly supplied by the museum. The larger of the three well-folded birds has writing on which says,'November 18, 1896. Made by L.N.Tolstoy in a train car going to Moscow. Gift for Mother.' I find it amazing that a flapping bird folded for a 10 year old boy on a train in 1896 has survived in this way. Litvinov and Mamin also give the following passage from the same first draft of 'What is Art?' 'The person who invented these cockerels must have been enchanted by his own discovery, and the joy is transferred to others. And that is why the making of a paper cockerel, strange as it may seem, is real art. I cannot refrain from observing that this was the only new work in the sphere of paper cockerels that I have encountered during the last sixty years. At the same time, the poems, novels and musical opuses that I have read during the same period run to hundreds, if not thousands. This is because cockerels do not matter, you might say, whereas poems and symphonies do. But I think the reason lies in the fact that it is much easier to write a poem, paint a picture, or compose a symphony than to invent a new cockerel.' Unfortunately these sentiments did not make it into the final version of his essay. ********** 1889 Diagrams for the Flapping Bird, under the title 'Le Martinet des Tourelles' (The Swift of the Turrets), appear in 'Jeux et Travaux Enfantins - Première partie: Le Monde en Papier' by Marie Koenig and Albert Durand, which was published by Librairie Classique A. Jeande in Paris in 1889. The text calls this design 'a Japanese toy, which the journal La Nature calls it a mechanical paper bird. It moves its wings if you pull the fold that forms the tail while holding the base of the wings near the neck between two fingers of the other hand'.

********** 1890 In December 1890 Miguel de Unamuno wrote a letter to Juan Azardun (Juan Arzadun Zabala (1862-1950) in which he mentions pajaritas 'that fly', a possible reference to the Flapping Bird. ********** The Flapping Bird also appears as 'A Mechanical Paper Bird' in 'Half Hours of Scientific Amusement' by Gaston Tissandier, translated by Henry Frith, which was published by Ward, Lock and Co in London, New York and Melbourne in 1890.

********** 1891 In 'Pleasant Work for Busy Fingers' by Maggie Browne, which was published by Cassell and Company in London in 1891.

********** 1893 As 'Una palomita de vuelo' in 'Cuestiones de Pedagogía Práctica: Medios de Instruir' by D Vicente Castro Legua, which was published by Libreria de la Viuda de la Hernando y Ca in Madrid in 1893. Infomation from Juan Gimeno.

********** 1894 Issue 1093 of 12th May 1894 contained an article by 'Dr Z...' headed 'Recreations scientifiques' and subheaded 'Papier decoupe formant un filet' which explains how to make the Fold and Cut Paper Trellis. The opening paragraph reads, roughly, 'We have previously published several recreations that can be made with paper; we gave the way of making a bird, whose wings can be made to move. This invention is Japanese; the Japanese made it known, with great success, at the Exposition of Paris in 1889.' However, footnote 1 makes it clear that the previous publication of the flapping bird in 'La Nature' was in 1885. Information from Michel Grand. ********** 1896 As 'Un pajaro mecanicol de papel' in 'Repertorio completo de todos los juegos' by de Luis Marco y Eugenio de Ochoa y Ronna, which was published in Madrid by Bailly-Bailliere e hijos in 1896. Information from Juan Gimeno.

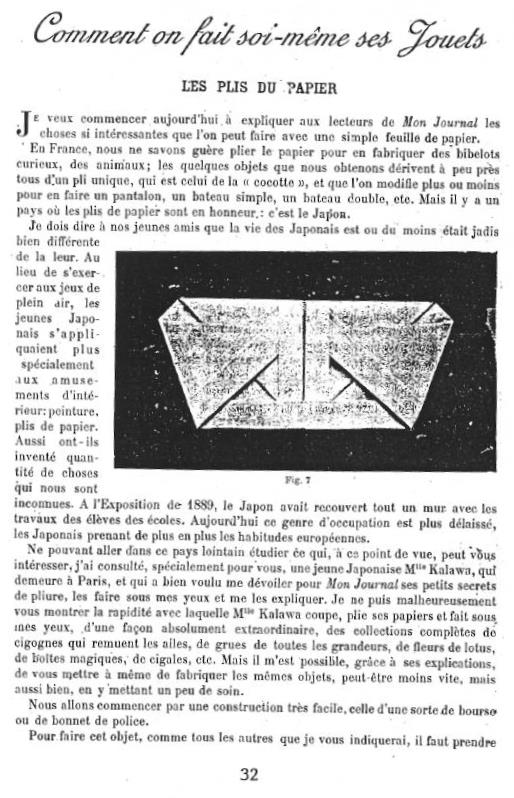

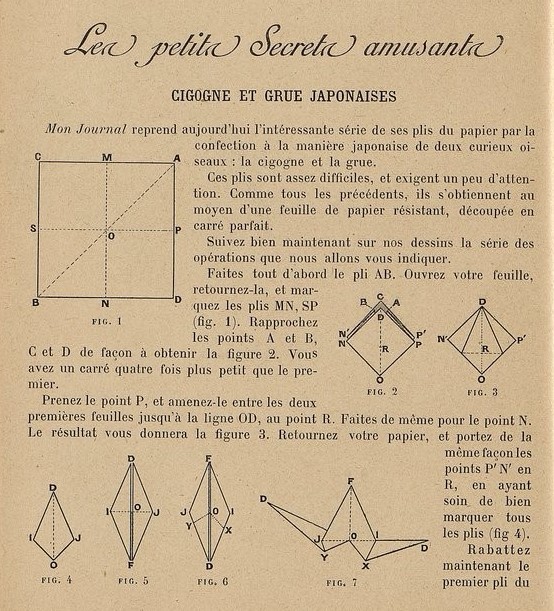

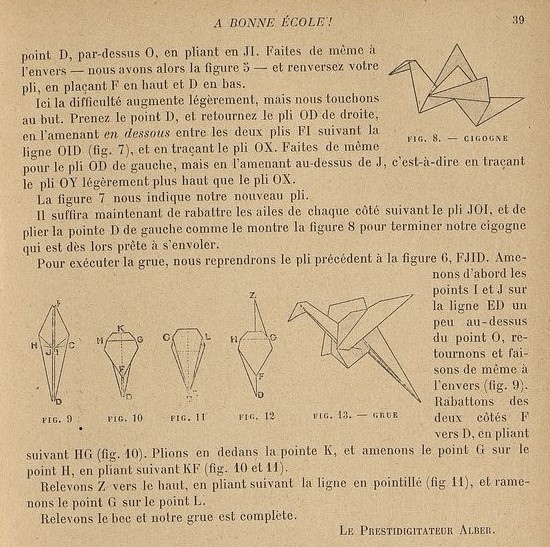

********** 1899 An article in the French children's magazine 'Mon Journal' by Alber, published on 21st October 1899, mentions 'cigognes qui remuent les alles' (swans which stir their wings). The article claims that the author learned the design in Paris from a Mlle Kalawa (and also seems to make a connection with the 1889 Exposition.) It is not clear the extent to which this information can be relied on. It is also worth noting that when the Flapping Bird design appears in the same magazine in 1902 (see below) the author does not mention that the wings will flap. The article says, roughly, 'I have to explain to our young friends that the life of the Japanese is, or once was, very different from theirs. Instead of playing outdoor games, young Japanese concentrate mostly on inside amusements: painting, folding paper. Also they have invented many things that are unknown to us. At the 1889 Exposition, Japan has covered a complete wall with the work of school children. Today this kind of occupation is more neglected, the Japanese acquiring more and more European habits. Unable to travel to this faraway country to study what, from any point of view, may interest you, I consulted, especially for you, a young Japanese woman, Mlle Kalawa, who lives in Paris, and was kind enough to reveal to me for Mon Journal her little paperfolding secrets, do them before my eyes and explain them to me. Unfortunately I cannot show you the rapidity with which Mlle Kalawa cuts, folds her papers and makes before my eyes, in an absolutely extraordinary way, complete collections of swans which stir their wings, cranes of all sizes, lotus flowers, magic boxes, cicadas etc. But I can, thanks to her explanations, explain to you how to make the same objects, perhaps not so quickly, but equally well, if you take a little care'

********** 1902 As 'Pajarita de movimiento' in 'Guia Practica del Trabajo Manual Educativo' by Ezequiel Solana, which was published by Editorial Magisterio Español in Madrid in 1902.

********** The design appears as 'Cigogne' (Stork) in an article by Albers-Graves in 'Mon Journal' of 18th October 1902 (along with the Paper Crane). The author does not mention that the wings will flap.

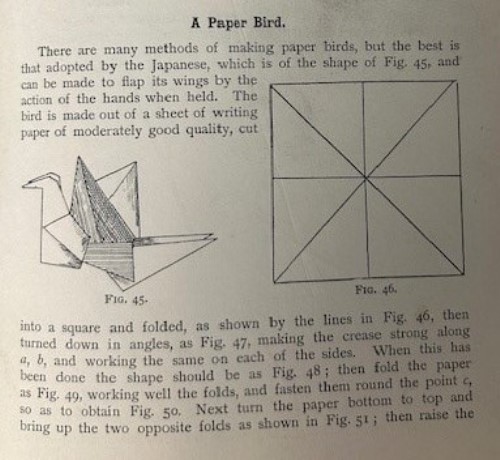

********** 1904 As 'A Paper Bird' in 'The Book of Indoor Games' by J K Benson, which was published by C Arthur Pearson Limited in London in 1904.

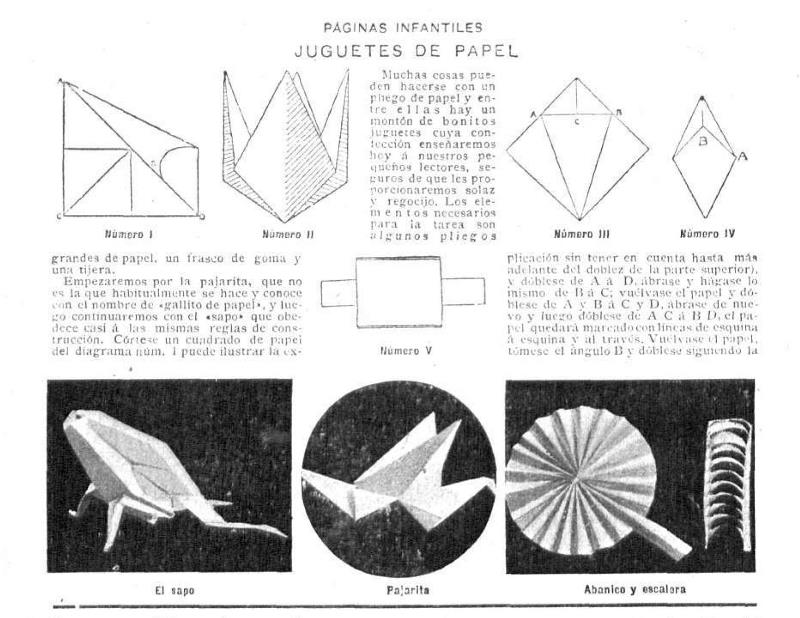

********** 1905 As 'la pajarita' in Issue 238 of the Buenos Aires edition of the magazine 'Caras y Caretas' of 25th March 1905.

********** 1907 As 'Palomita di movimiento' and 'Palomita de vuelo' in an article titled 'El trabajo manual escolar' by Vicente Casto Legua in the January 1907 issue of the Spanish magazine 'La Escuela Moderna' which was published in Madrid by Los Sucesores de Hernando.

********** 1908 In the last ever issue of the Catalan satirical magazine 'La Campana Catalana', published in Barcelona on 29th April 1908, in a cartoon by Apeles Mestres which pictures a variety of paperfolding designs. This pictorial story had previously been published in his Llibre Vert III in 1883.

********** Issue 487 of the Buenos Aires edition of the magazine 'Caras y Caretas', published in February 1908 contained a three-page laudatory article about Miguel de Unamuno which included a picture of him folding 'pajaritas de papel' at his desk. One of these is clearly the Flapping Bird.

********** Instructions for making the Flapping Bird appeared, under the title of 'La pajarita di movimiento', in the Buenos Aires edition of 'Caras y Caretas' for 26th September 1908, issue 521.

The final paragraph, roughly translated, mentions that, 'under the name of pajaritas, lanterns, flowers, fans and all kinds of animals are also included' and recommends to the reader 'the ingenious article of the festive Spanish writer Sinesio Delgado, which carries the suggestive and original title of 'Pajaritologia''. ********** The Flapping Bird also appears, as 'La cigogne' in 'Les Petits Secrets Amusants' by Alber-Graves, which was published by Librairie Hachette in Paris in 1908. he author does not state that he wings will flap although he does say this about 'La grue', a version of the Paper Crane which immediately follows it in the book. See Introduction at the head of this page.

********** 1910 A version of the article from the 18th October 1902 issue of 'Mon Journal' (see above) appeared in 'La Poupee Modele' of May 1910. ********** As 'Storch' (Stork) in 'Allerlei Papierarbeiten' by Hildergard Gierke and Alice Kuczynski, which was published by Drud und Verlag B G Teubner in Leipzig and Berlin in 1910. There is no evidence that the author knew that the wings could be made to flap.

********** The Flapping Bird appeared as the 'Flying Bird' in 'Studies in Invalid Occupation' by Susan E Tracy, which was published by Whitcomb and Barrows in Boston in 1910. The author states that the design is of Japanese origin.

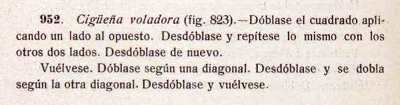

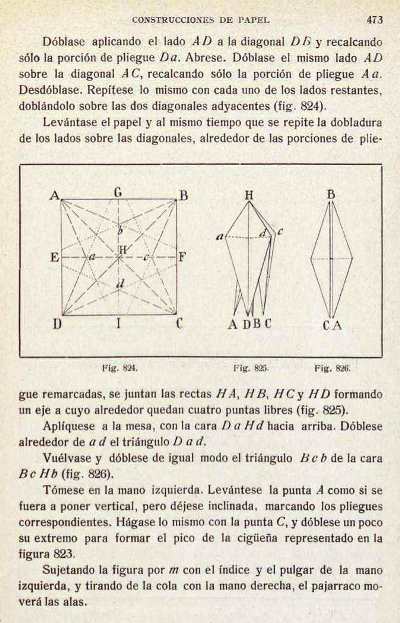

********** 1918 As 'Ciguena voladora' in 'Ciencia Recreativa' by Jose Estralella, which was published by Gustavo Gili in Barcelona in 1918.

********** As 'Pajaro Volador' in 'Juguetes de Papel', which was published by Editorial Muntanola in Barcelona 1918. The author is aware that the wings will flap but does not say how this is achieved.

********** 1920 In 'Paper Magic' by Will Blyth, which was first published by C Arthur Pearson in London in 1920.

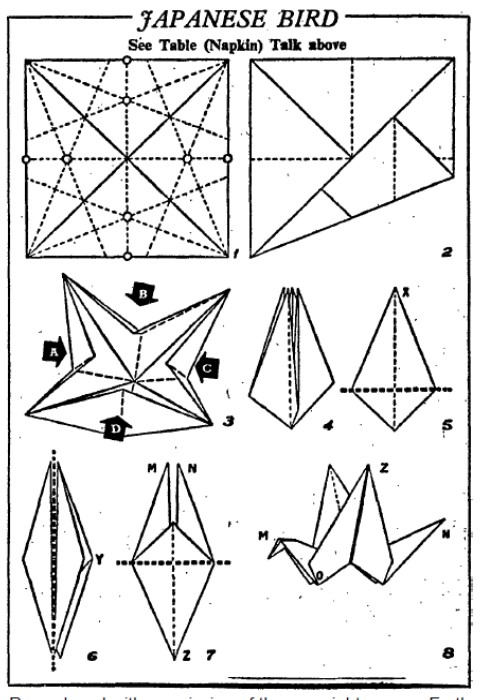

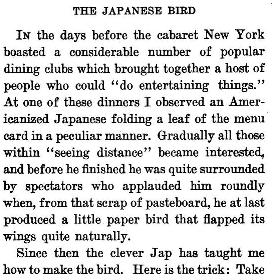

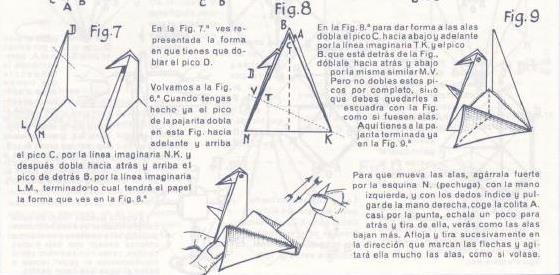

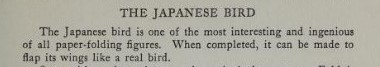

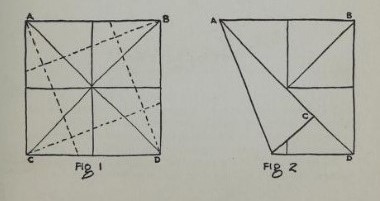

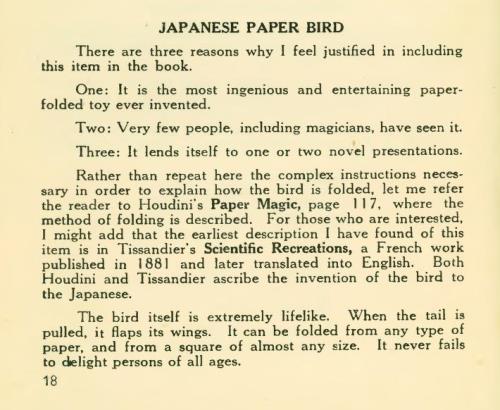

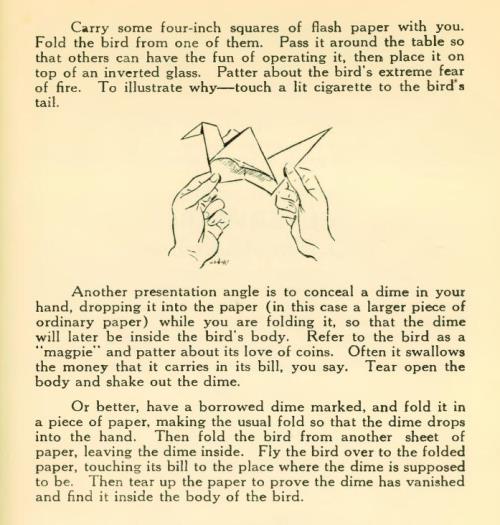

********** 1922 In 'Houdini's Paper Magic', which was published by E P Dutton and Company of New York in 1922. Houdini published this design under the title 'The Japanese Bird'. He says he learned this design from an 'Americanised Japanese' who he goes on to call a 'clever Jap'

The text goes on to suggest that the body should be inflated in the way that the body of the Paper Crane was often inflated in the Japanese tradition.

********** 1923 As 'Pajaro con Alas Moviles' in 'Trabajos Manuales y Juegos Infantiles' by Francisco Blanch, which was published by I. G. Seix y Barral Hermanos S.A.- Editores in Barcelona in 1923.

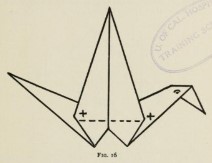

********** 1928 In 'Fun with Paperfolding' by William D Murray and Francis J Rigney, which was published by the Fleming H Revell Company, New York in 1928,, as just 'The Bird'. The diagrams show how to make the design using the Preliminary Base method and using a crimp rather than a reverse fold to create the head.

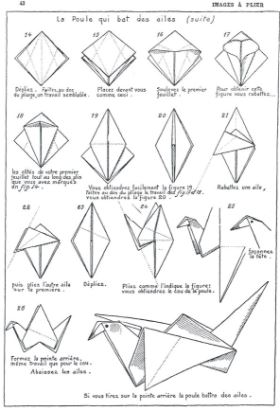

********** 1929 As 'La Poule Qui Bat Des Aisles' in the issue of the French children's magazine 'L'Age Heureux' of 15th August 1929.

********** In the 1st January 1929 issue of 'Revue des Deux Mondes, there is mention of the flapping bird, as 'une cocotte en papier qui bats des aisles', in the final sentence of page 171, of the article 'L'etrange, Petit Garcon' by Gerard D'Houville. Information from Michel Grand.

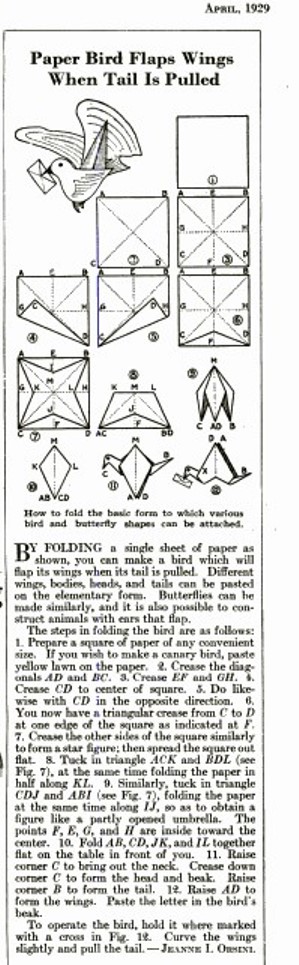

********** In Popular Science Magazine for April 1929. Information from José Tomas Buitrago.

********** 'Un oiseau volant', probably, though not certainly, the Flapping Bird, is mentioned in a story titled 'Une Rude Emotion' by J de Chateauli in the July 6th 1930 issue of the French children's magazine 'Guignol cinema des enfants'. Information from Michel Grand.

********** 1931 As 'La Poule Qui Couve' in the issue of 'Le Memorial' for 18th June 1931. There is no evidence in the article that the author was aware that the wings could be made to flap.

********** In 'La Nature' Issue 2870 of 1st December 1931 in an article by Alber headed 'Pliage de papiers' and subheaded 'L'oiseau qui bat des ailes'.

********** As 'Fliegender Vogel' in the revised 3rd edition of 'Lustiges Papierfaltbüchlein' by Johanna Huber, which was published by Otto Maier in Ravensburg, Germany in 1931. There is no evidence that the author was aware that the wings could be made to flap.

********** 1932 Diagrams also appear in 'Winter Nights Entertainments' by R M Abraham, which was first published by Constable and Constable in London in 1932.

********** As 'La Poule Qui Bat Des Ailes', in Booklet 3 of 'Images a Plier', a series of 6 booklets published by Librairie Larousse in Paris in 1932.

********** As 'Ciguena' in Booklet 1 of 'Figuras de Papel', a series of 3 booklets published by B Bauza in Barcelona in 1932.

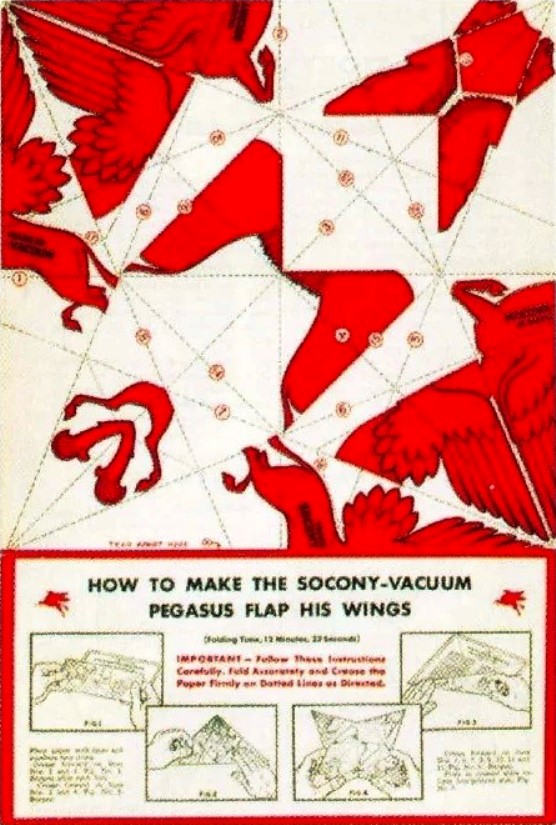

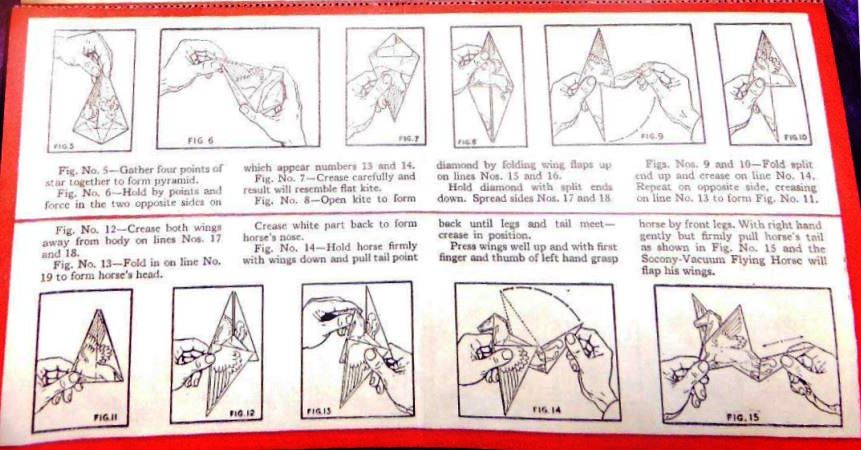

********** 1934 In 1934 the Socony-Vaccuum Oil Company Incorporated issued an advertising flyer which folded up to form a Flapping Bird decorated to look like their logo of a Pegasus / Flying horse.

********** 1936 An article titled 'Las Papirolas del Doctor Solorzano: Poligonos de papel que abre un nuevo horizonte para la cienciass papirolas del Doctor Solorzano' by Carlos Alberto Leumann was published in 'La Prensa, Diario de Buenos Aires' on 15th November 1936. The first paragraph stated: 'Un día, prestidigitadores japoneses maravillaron a los públicos teatrales de Europa con una encantadora novedad en la historia insignificante de este juego. Mostraban un cuadrado de papel muy blanco, en plena luz, y luego, ligeramente, lo convertían en un pájaro que sabía agitar las alas. Era que el cuadrado de papel tenía ya hechos los dobleces necesarios para formar la pajarita y para el alígero; la misma luz excesiva servía para ocultar la marca de los dobleces, y con el manipuleo hábil parecía el pájaro salir inmediatamente del papel blanco.' Roughly translated this says: 'One day, Japanese conjurers amazed the theatrical audiences of Europe with a charming novelty in the insignificant history of this game. They showed a square of very white paper, in full light, and then, slightly, turned it into a bird that knew how to flap its wings. It was that the paper square had already made the necessary folds to form the pajarita and for the light; the same excessive light served to hide the mark of the folds, and with the skillful manipulation the bird seemed to immediately come out of the white paper.' ********** As 'The Japanese Paper Bird' in 'More Things Any Boy Can Make' by Joseph Leeming, which was published by D Appleton-Century Company in New York and London in 1936.

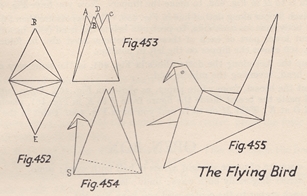

********** 1937 As 'The Flying Bird' in 'Paper Toy Making' by Margaret Campbell, which was first published by Sir Isaac Pitman and Sons Ltd in London, probably in 1937, although both the Foreword and Preface are dated 1936, which argues that the book was complete at that date. It is interesting for the way in which the tail is set in an upright position. In his Preface to the book Margaret Campbell's son, Roy, wrote: 'This hobby is full of homely wisdom. But it also has among its fanciers several very outstanding intellects: for example, Leonardo, Shelley and Unamuno. I can quite imagine that the traditional flying bird might have been one of the lighter butterfly-fancies of Leonardo's brain when he was suddenly struck with the beauty or intelligence of a child and turned aside to amuse him.' It hardly needs to be said that there is no historical evidence to back up this rather whimsical notion.

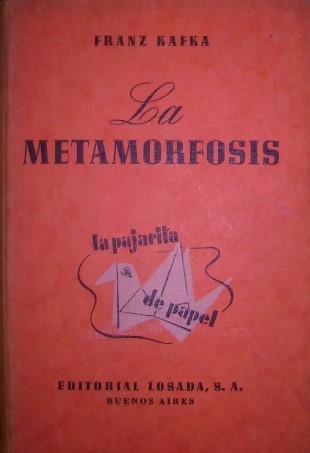

********** 1938 According to David Lister's article on the origins of the Flapping Bird, available on the Lister List from the British Origami Society website, the information about the origin of the Flapping Bird given in the 1936 article in La Prensa (see above) was repeated in the Prologue to Dr. V. Solorzano Sagredo's "Papirolas 1er Manual" published in Buenos Aires in 1938. That prologuewas also written by Carlos Alberto Leumann. ********** 1938 to 1948 A series of 18 books was published between 1938 and 1948 by Editorial Losada S A of Buenos Aires under the title of 'La Pajarita de Papel'. The symbol of the series was not the Cocotte / Pajarita but the Flapping Bird, which appeared on the covers, title page and endpapers of the books. The image below is the cover of the earliest of these books, Franz Kafka's 'The Metamorphosis' translated by Jorge Luis Borges.

*********** 1939 As 'Palomita voladora' in 'Trabajo Manual Educativo' by Araminta V Aramburu, which was published by F Crespillo in Buenos Aires in 1939.

********** As 'Paloma' in 'Plegado' by Rufino Yapur, which was published by Editores Independencia in Buenos Aires in 1939.

********** As 'Pajarita que mueve las alas' in 'El Mundo de Papel' by Dr Nemesio Montero, which was published by G Miranda in Edicions Infancia in Valladolid in 1939. There is a curious similarity between the final illustration of the design in this book and that in 'Paper Toy Making' by Margaret Campbell above.

********** As 'The Japanese Bird' in 'Fun with Paper' by Joseph Leeming, which was published by Spencer Press Inc in Chicago in 1939.

********** As 'Pajarita de Alas Movibles' in 'El Plegado y Cartonaje en la Escuela Primaria' by Antonio M Luchia and Corina Luciani de Luchia, which was published by Editorial Kapelusz in Buenos Aires in 1940.

********** 1941 As 'La Paloma' in 'Papiro-Zoo: Manual practico de cocotologia o papirologia' by Giordano Lareo, which was published by Larco in Buenos Aires in 1941.

********** In 'After the Dessert' by Martin Gardner, which was published by Max Holden in New York in 1941, where the author suggested several presentations by which the Flapping Bird could be included as part of a magic act, including folding it from flash paper.

********** 1945 'Bill Folds' by Al O'Hagan published by George Snyder's Magic Shop of Cleveland, Ohio in 1945. It included diagrams for folding 'A Bird' from a dollar bill.

********** 1946 In the April 1946 issue of Popular Mechanics magazine, whichj contained an article, entitled 'Folding Paper is Fun for Everyone', which contained diagrams for the Flapping Bird . I learned about this article from Oschene.

********** In 'The New Rupert Book', which was published by the Daily Express in 1946.

********** 1948 In 'The Art of Chinese Paper folding for Young and Old' by Maying Soong, which was published by Harcourt Brace and Company of New York in 1948, includes diagrams for the Flapping Bird under the title 'Bird Flies In Your Hand'.

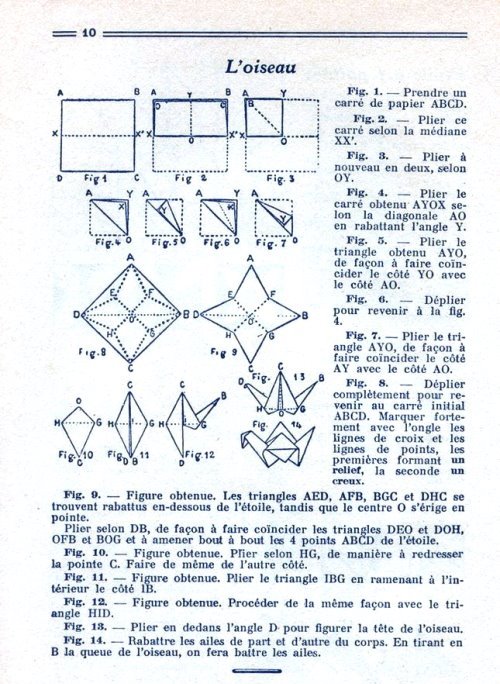

********** 1951 As 'L'oiseau' in 'Occupons nos doigts' by Raymond Richard which was published by Les Editions du Cep Beaujolais in Villefranche-sur-Rhone in 1951.

********** As 'La Pajarita Voladora', made in a very unique way, in 'Papiroflexia' by Elias Gutierrez Gil, which was self-published in 1951.

********** 1951 As 'Pajarita que vuela' in Plegado laminas published by Della Penna, April 1951.

********* 1952 As 'Pajarita Voladora' in 'Una Hoja de Papel' by Lorenzo Herrero, which was published by Miguel A Salvatella in Barcelona in 1952.

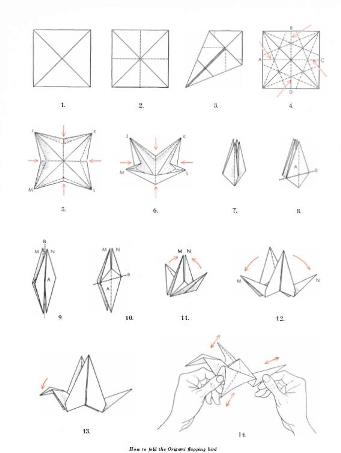

********** 1953 'Ireland's Yearbook', a magic compendium, for 1953, contained an article titled 'A Japanese Bird' which showed how to fold an 'origami paper crane'. (Information from conjuringarchive.com) ********** 1956 As 'The Flying or Flapping Bird' in 'Paper Magic' by Robert Harbin, which was published by Oldbourne in London in 1956. The text notes, 'Japanese masterpiece: The Classic Paper Fold'.

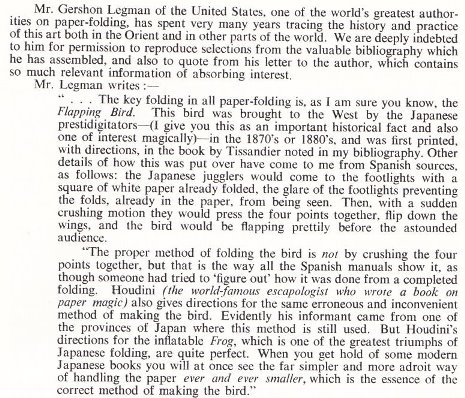

The Introduction to the book contains a section relating to this design which reads:

See entry for 1936 above for further information. ********** The Flapping Bird also appears: 1959 In an article titled 'About origami, the Japanese art of folding objects out of paper' by Martin Gardner which was published in the July 1959 issue of 'Scientific American'.

********** The 'Table Talk by Pendennis' column of 'The Observer' for Sunday 23rd August 1959, which was written by Anthony Sampson, contained instructions for folding the Flapping Bird.

********** As 'Flying Bird', in 'Fun-time Paper Folding' by Elinor Tripato Massoglio, which was published by Childrens Press in Chicago in 1959.

(This entry is also made in the Western Europe / The USA section of this page) ********* 1960 As 'Flapping Bird' in 'Origami: The Oriental Art of Paper Folding' by Harry C Helfman, which was published by Platt and Munk Co Inc in New York in 1960. This design is said to be of Japanese origin.

********** 1961 As 'The Japanese Flapping Bird' in 'The Art of Origami' by Samuel Randlett, which was published by E P Dutton in New York in 1961.

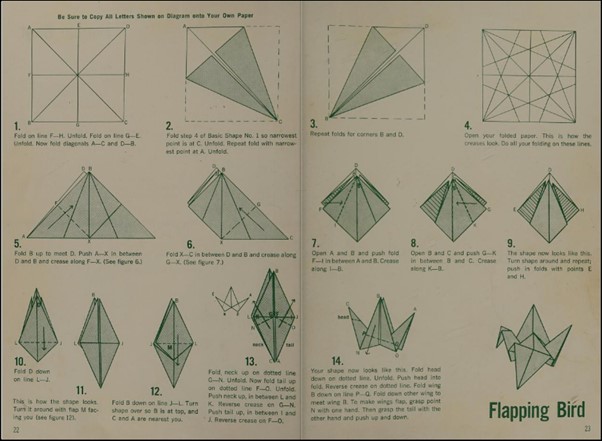

********** A printed template from which the Flapping Bird could be folded featured in an advert for Nibroc Offset which appeared in the US magazine 'Print' in March-April 1961 (Vol 15 Iss 2).

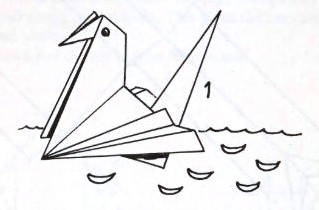

********** A seated variant, made by adding additional folds to the wings. appeared as 'The Swan' in 'How to Make Things Out of Paper', which is a translation into English, published in 1961 by Sterling Publishing Co Inc in New York, of Walter Sperling's 1955 book 'Papier-Spiele'.

********** The Flapping Bird also appeared: 1962 As 'Flapping Dove' in 'Origami Tehon' by Akira Yoshizawa, which was published by the International Origami Research Society in 1962.

********** 1963 As 'Flyng Bird' in the second edition of 'Het Grote Vouwboek' by Aart van Breda, which was published by Uitgeverij van Breda in 1963.

*** The seated variant also appeared in this work as 'Zwaan'.

********** A Flapping Bird folded from a dollar bill appears in 'The Folding Money Book', which was published by The Ireland Magic Co in Chicago in 1963.

********** 1964 In 'Secrets of Origami', by Robert Harbin, which was published by Oldbourne Book Company in London in 1964, where it is said to be Japanese.

********** 1968 In 'Teach Yourself Origami: The Art of Paperfolding' by Robert Harbin, which was published by The English Universities Press in 1968.

********** In 'Your Book of Paperfolding' by Vanessa and Eric de Maré, which was published by Faber and Faber in London in 1968, where it was is to be a traditional Japanese design.

********** 1970 In an article published in Woman's Own magazine of March 1970.

********** |

|||||||

.jpg)