| The Public Paperfolding History Project

x |

|||||||

| Historia de Unas Pajaritas de Papel by Miguel de Unamuno, 1888 | |||||||

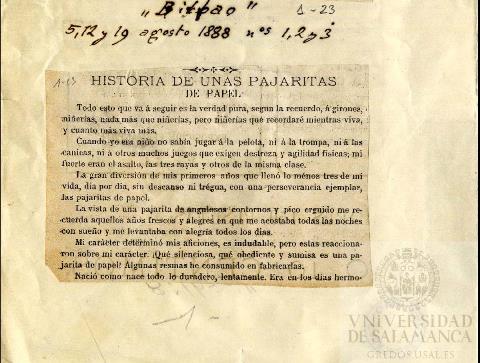

In 1888, when he was 24, Miguel de Unamuno wrote 'Historia de Unas Pajaritas de Papel', an account, in three parts, of how, in 1874, when he would have been 10, he and his cousin folded and played with paper pajaritas and other toys during the bombing of Bilbao during the Third Carlist War. This account was most probably written in the hope that it would be accepted for publication in a magazine, but, as far as I know, this did not happen. The original typewritten manuscript is now held in the archives of the University of Salamanca. The full document can be viewed at https://gredos.usal.es/bitstream/handle/10366/84004/CMU_1-23.pdf?sequence=1

A transcript of the full original Spanish text (courtesy of Juan Gimeno) and a complete rough English translation are given below. The paper birds Don Miguel writes about in this account are normally referred to as 'pajaritas de papel' (little paper birds) but on one occasion he refers to them as 'pajarillos' (sparrows). It seems clear from the context that these paperfolds are the familar Cocotte / Pajarita design. Don Miguel describes how he and his cousin folded and played increasingly complex games with Cocottes / Pajaritas: 'It was in the beautiful days of the spring of 1874, during the bombing of my village. Something had to do with spending time in the dark, damp fish market that needed daylight, for the only doors open to it had been boarded up with mattresses. We heard nothing but the army, battles, Carlists and Liberals, bombs and assaults and the only thing that happened to us was to make about two hundred sparrows (pajarillos) (in France they are cocottes), train them four deep and simulate combat.' 'Originally those original birds lived in the wild, without police or hierarchical order, without their name or occupation, without a fixed residence, wandering from here to there, from box to box, and what is more surprising, without females nothing worth it, because this was born later. They were produced autonomously and by spontaneous generation, informed by my hands and those of my cousin, their creators, of the raw material of a white paper.' He states that these Cocottes / Pajaritas were of two types, folded from doubly and triply blintzed squares: 'There were two breeds, a slimmer and slimmer, made of two doubles, and a thick, bearded and pocketed, made of three.' A female version of the Cocotte / Pajarita was devised by 'raising its beak'. 'Death was already regularized, but birth was not, because, frankly, being born by birlibirloque, by spontaneous generation, is a corny thing. So we thought that it was not right for the bird to be alone and we devised a companion similar to him. By raising its beak, the way its legs are made, instead of lowering it, the female was already invented. And from then on we made the birds, we folded their beaks inwards and thus they were placed between the folds of the females until the latter, with the bustle of going and coming back, were released, that is, they gave birth.' ********** The original Spanish text HISTORIA DE UNAS PAJARITAS DE PAPEL I (“Bilbao” 5 de agosto de 1888) Todo esto que va a seguir es la verdad pura, según la recuerdo, a jirones, niñerías, nada más que niñerías, pero niñerías que recordaré mientras viva, y cuanto más viva más. Cuando yo era niño no sabía jugar a la pelota, ni a la trompa, ni a las canicas, ni a otros muchos juegos que exigen destreza y agilidad físicas; mi fuerte era el asalto, las tres rayas y otros de la misma clase. La gran diversión de mis primeros años que llenó lo menos tres de mi vida, día por día, sin descanso ni tregua, con una perseverancia ejemplar, las pajaritas de papel. La vista de una pajarita de angulosos contornos y pico erguido me recuerda aquellos tres años frescos y alegres en que me acostaba todas las noches con sueño y me levantaba con alegría todos los días. Mi carácter determinó mis aficiones, es indudable, pero éstas reaccionaron sobre mi carácter. ¡Qué silenciosa, qué obediente y sumisa es una pajarita de papel! Algunas resmas he consumido en fabricarlas. Nació como nace todo lo duradero, lentamente. Era en los días hermosos de la primavera de 1874, durante el bombardeo de mi villa . En algo había de pasar el tiempo en la lonja oscura y húmeda que necesitaba luz de día, pues las únicas puertas abiertas a ella habían sido tapiadas con colchones . No oíamos hablar más que del ejército, de batallas, de carlistas y liberales, de bombas y de asalto y lo único que nos ocurrió fue hacer unos doscientos pajarillos (en Francia son cocottes), formarles de cuatro en fondo y simular combates. Una jaula de grillo preparada servía de lámpara, con una cerilla, luz eléctrica le llamábamos, y a la luz aquella tan escasa y menguada íbamos haciendo recorrer la mesa a todos los pajarillos, paso a paso, mientras cantábamos un paso fúnebre que habíamos oído. En la lonja tuvieron humilde origen las naciones poderosas de esforzados pajarillos de papel, los imperios vastísimos que dominaron los cajones y armarios de mi casa y llevaron su bandera victoriosa hasta el último rincón de una huerta de Olabeaga. Vivieron en su origen aquellas originales pajarillas en estado salvaje, sin policía ni orden jerárquico, sin que tuviera ninguna su nombre ni su oficio, sin residencia fija, errando de aquí allá, de caja en caja, y lo que es más sorprendente, sin hembras ni cosa que le valga, pues esto nació más tarde. Se producían autónomos y por generación espontánea, informados por mis manos y las de mi primo, sus creadores, de la materia prima de un blanco papel. Había dos razas, una más esbelta y delgada, hecha de dos dobles, y otra gruesa, barbuda y con bolsillos, hecha de tres. Éramos dos creadores, y este dualismo hizo fueran dos las gentes, por necesidad enemigas, pues habían nacido y vivían para luchar bajo aquella providencia maniquea. Milicia era su vida sobre la tierra, que así complacían a su creador y dueño. En aquellos primeros tiempos de la edad de oro todos obraban y obedecían a un mismo plan, todos provenían del mismo papel y de las mismas manos. Aún el individuo no había brotado de la masa, aquello era objetivismo puro, en términos filosófico-serios. Sus combates eran sencillísimos e inofensivos; consistían en colocarse los ejércitos frente a frente, y esperar resignados a la bola de papel con que yo barría las filas de mis enemigos, y mi primo las de los suyos. Eran héroes oscuros, víctimas de la fatalidad, que peleaban al amparo de sus deidades protectoras, al modo que peleaban junto a los muros de Ilión los rudos héroes de Homero. Aún no había poetas que los cantaran ni había llegado a ellos la musa de la Historia. Apenas recuerdo cosa fija de tan remotos tiempos. El primer rey histórico fue un muñeco de cera imitando un mono, con sus brazos y piernas movibles por medio de alfileres, engalanado con papelillos azules, rojos y dorados. Vestía un tricornio y montaba un caballo también de cera. Éste fue Mono I el Sabio. Lo de sabio venía como consecuencia de lo de mono; no conocíamos más que los de las colecciones de perros y monos sabios. A Mono I el Sabio sucedió Amadeo I, fabricado con una cabeza del rey Amadeo recortada de un sello. Éste no hizo nada notable. Héroes de esta edad fueron Lage, figura de un viejo francés recogida de una caja de fósforos franceses, en que se leía al pié: L’age des espérances. Otro era una caricatura de Thiers , también de una caja de cerillas, que llegó a ser con el tiempo, bajo el nombre de Heredia, médico celebérrimo, autor de un tratado de anatomía pajaresca de que hablaré más adelante. *** HISTORIA DE UNAS PAJARITAS DE PAPEL II (“Bilbao” 12 de agosto de 1888) Las noticias de aquel tiempo remoto, recogidas por la tradición cuando ésta vivía fresca y reciente, estaban archivados en la verídica y puntual relación de toda esta historia de la cual relación sólo conservo dos librillos. En torno de Mono I, de Amadeo, de Lage y de otros extraños personajes empezaron a agruparse las pajarillas de papel. Muy pronto adquirieron grados y honores, y desearon fijarse en moradas estables, más que por la necesidad de hogar y techo, para poder organizar asedios de plazas fuertes, asaltos y defensas. ¿Para qué sirve una ciudad si no es para ser tomada? Con cajas, pedazos de madera y otros trastos, se armaba sobre la mesa la ciudad de quita y pon. Así nació Huleón., célebre por la batalla de su nombre. Llamábase Huleón por haberse edificado sobre el hule que cubría la mesa. ¡Qué combate fue aquel! ¡Qué golpes de la bola de plomo, la terrible bola de plomo contra los muros de la soberbia Huleón! De nada sirvieron ni la escala de palillos e hilo, ni la lluvia de proyectiles. Ni Bilbao con ser Bilbao resistió a los carlistas con tanto denuedo. Después de Huleón nació Caberonte, nombre que se dio a la nueva ciudad por lo sonoro y nada significativo. ¿Qué dire de los combates navales, en balsas y barcos sobre un barreño lleno de agua? Bolazo va, bolazo viene, el que caía caía y allí se remojaba. El agua al ser agitada se vertía y hubo que suspender las naumaquias por mandato superior, superior al de los creadores de aquella gente brava. La semana era cosa pesada, todos los días al colegio por la misma calle, a repetir las mismas cosas; llegábamos al sábado verdaderamente cansados. La alegría del domingo era la lluvia, el cielo gris para poder quedar en casa. ¡Qué hermosa tarde para combates una tarde lluviosa! Las naciones crecían, aparecían cada día nuevas pajaritas a engrosar los ejércitos y el exceso del mal trajo el remedio. Y fue éste que se nos ocurrió hacer mortales a las pobres pajarillas, sin ellas comerlo ni beberlo, sin haber probado el fruto del árbol prohibido. De por sí, intrínsecamente, eran inmortales, pero a nosotros, sus creadores, nos pareció soso eso de tener que renunciar a la matanza y contentarnos con derribarlas. Aquello no tenía gracia, ¡vaya una cosa! Y de común acuerdo designamos lo que se tendría por herida, curada la cual volvía el combatiente a la pelea, y lo que se habría de considerar como muerte. Se hicieron entonces horribles combates. Armado cada uno de nosotros con su alfiler empezaba a rasgar a los heroicos pajarillos del otro, hasta que dada tregua a una voz, se procedía a separar los muertos de los heridos y a curar éstos con parches de papel y goma. ¡Qué dolor más sincero al ver muertos, con la cresta destrozada a tantos bravos combatientes! Era, en cambio, una delicia colocarles el parche, trofeo glorioso con que se señalaba el glorioso destino de tan insignificantes seres. Resultaba que para aplicarles el parche había que abrirles, deshacer sus pliegues, desgarrar sus articulaciones, es decir, desmembrarlos, todo lo cual es una anomalía monstruosa. ¿Cuándo se ha visto descoyuntar a un enfermo para hacerle la cura, abrirle en canal para cerrarle una herida? Estaba visto, que en aquella sociedad primitiva la cirugía estaba atrasadísima. Entonces nació la idea de curarles sin abrirles nada, para lo cual había que hacerles un corte cerca de la herida, tomar medidas, calcular el tamaño, forma y pliegues del parche, todo lo cual exigía un detenido estudio de la anatomía papeli-pajaresca. Y hétenos allí inventando nombres para tal pliegue y cual doble, para este ángulo y el otro, nombres extravagantes que no eran más que los del cuerpo humano, en el idioma de las pajarillas. Este tratado de anatomía se publicó a nombre de la caricatura de Thiers. Es de saber que tenían su idioma, mejor dicho, sus idiomas, uno de ellos el vascuence; de capricho los demás. La inmortalidad les había dado insignificancia, todos eran iguales en ella. Pero desde que quedaron sujetos al alfiler de la muerte resistían unos más que otros, llenos de parches aquellos, éstos destrozados en la flor de la edad, en la primera batalla, y así es como el individuo brotó de la masa, tuvo su nombre, su historia, fue más que un número. Sus nombres eran nombres de capricho, los unos sacados de la Araucana, de Ercilla , que leíamos entonces para enardecer nuestro espíritu bélico; y allí hubo Cayuguán, que dio nombre a los cayeguanos, Caupolicán, Lautaro, etc. Hubo también Atila, un gigante, como que él sólo necesitó un pliego de los mayores. Les conocía yo uno a uno, apreciaba sus virtudes. Nunca olvidaré al celebérrimo Lunkekwig, nombre que le inventé por no significar nada y sonarme con sus kas y uves dobles a bárbaro y altisonante. Estaba el tal acribillado a alfilerazos, y forrado de parches, pero al fin murió el pobrecito, ¡qué lástima! Fue una de mis mayores penas. La muerte ya estaba regularizada, pero no lo estaba el nacimiento, porque, francamente, eso de nacer por obra de birlibirloque, por generación espontanea, es cosa cursi. Entonces pensamos que no estaba bien que el pajarillo esté sólo e ideamos compañera semejante a él. Con levantarle el pico, al modo que se le hacen las patas, en vez de bajárselo, ya estaba inventada la hembra. Y desde entonces hacíamos los pajarillos, les doblábamos hacia adentro el pico y así eran colocados entre los pliegues de las hembras hasta que a éstas con el trajín de ir y volver se les soltaban, es decir, parían. Y hubo matrimonios, registro civil, para aquellos amores, castísimos por supuesto, pues allí no había más engendradores que nosotros; todo se hacía por obra y gracia nuestra, y el pretendido padre servía para que el pajarillo nuevo se llamara «tal, hijo de cual». Y como consecuencia y antecedencia de los amores hubo raptos. Aquello se hundía, esto eran fulgores que anunciaban la irrupción de ideas nuevas, el despertar de otra vida que echaría al traste a los inocentes y sencillos pajarillos de papel. Ya las pobres eran poco para encarnar mis ideas; el amor que crea sociedades las destruye. *** HISTORIA DE UNAS PAJARITAS DE PAPEL III (“Bilbao” 19 de agosto de 1888) Pero, ¿cómo dejaré de contar la riqueza inagotable de aquel mundo? Hubo leyes escritas a modo de decálogo, promulgadas solemnemente y grabadas en caracteres griegos en la tapa de la caja en que se recojía a los pajarillos. Además de las dos naciones rivales, tenía que haber una irrupción de los bárbaros, sin ella no concebíamos la historia, y la hubo, la de los cayeguanos, notables por su barbarie, que después de victoriosos se civilizaron. Leíamos entonces a Julio Verne y al capitán Mayne Reid, y como era soso un mundo sin animales los hicimos de cartón, de extrañas formas, con grandes alfileres por cuernos unos, con una perlita falsa de abalorio al final de un hilo que hacía de rabo otros, otros con pecho de papel de goma, y todo ello para que en vez de ser provistos de alfileres, perlas , papel de goma y otros útiles por una divinidad pródiga, tuvieran que cazarlos con peligro de su vida. Se organizaron cacerías que se efectuaban encima de la mesa. Los animales se defendían a alfilerazos. No todos cazaban, pero los otros tenían para comprar los productos de la caza, dinero, pues había monedas que se sacaban en papel frotándole con lápiz sobre un perro chico o grande y pegadas las dos caras con oblea, había billetes de banco..., ¿Qué no habría allí? Fui a pasar el verano a Olabeaga y llevé allí una expedición, armada de punta en blanco. Allí, en un rincón de la huerta establecieron su colonia, casuchas de arcilla dentro de una empalizada y bajo un emparrado. ¡Qué gusto cuando llovía y quedaban deterioradas las casuchas, llenas de barro! Yo entonces creía que el mayor gusto de una navegación es naufragar; ¡son tan bonitos los naufragios de Julio Verne! ¡Lástima que en la huerta no había una isla desierta, y no podían morir de hambre o de escorbuto las pajarillas! Una lluvia fuerte arrastró a casi todas y así tuvo dramático fin la colonia de Olabeaga. Aquello se fue sutilizando, bizantinizándose poco a poco y llegó un día en que a pesar de todo fueron pequeño cuerpo para las ideas nuevas y entonces dejé a las pajarillas con pena. ¿Qué se hicieron aquellos ejércitos ignorados, la alegría de mi infancia? ¿A dónde fueron tantos silenciosos y pacientes héroes, juguete de potencias superiores? Brotaron de la materia cuando los llamé a la vida, vivieron a mi albedrío y cuando enojado ya de niñerías les arrojé al olvido, fueron tan resignados como habían venido a la vida. Cada vez que veo o hago una pajarita de papel, recuerdo mis alegres días del bombardeo, el germinar de mis ideas, la formación lenta de mi espíritu y todo aquel mundo vivo, variado y fresco que después de enriquecer mi fantasía y excitar mi inteligencia fue a morir al rincón oscuro donde mueren los juguetes desdeñados del niño. Otros se criaron en el campo, corriendo por él, respirando en el aire aromas de huerta y oyendo cantar a los pájaros de carne y hueso; yo entre calles, rompiendo botas por ellas, encarnando mis ideas en pajarillas de papel y prestándoles vida. Me creo en el deber de dedicar este recuerdo, estéril para ellos, a los que fueron mis compañeros de infancia. ¿Quién puede jurar que en aquellos papelitos inanimados, inertes y fríos no hubiera una sombra de conciencia? No yo, que nunca he sido pajarillo de papel. Cuando oigo tantas tonterías, tanto tomarlo todo en serio, tanto charlar de interiores que no se ven, recuerdo a mis obedientes y silenciosas pajaritas que vivían lejos de la porquería que amontonan los tontos como escarabajos peloteros. Los hombres de carne debíamos tomar por modelo, no sólo a hormigas y abejas, sino también a aquellos pueblos de papel, libres y obedientes, felices siempre, resignados a la vida y a la muerte, píos hacia su creador y animados todos por una misma voluntad y un mismo fin. Conservo aún como reliquia de aquellos tiempos dos, los únicos que se han salvado, de los librillos en que llevábamos los anales de aquella gente. ********** A rough English translation STORY OF A FEW PAPER BIRDS I (“Bilbao” 5th August 1888) All this that is going to follow is the pure truth, as I remember it, in shreds, trifles, nothing more than trifles, but trifles that I will remember as long as I live, and the longer I live, the more. When I was a child I did not know how to play ball, or the trunk, or marbles, or many other games that require physical dexterity and agility; my strength was the assault, the three stripes and others of the same class. The great fun of my first years that filled at least three of my life, day by day, without rest or truce, with exemplary perseverance, the paper pajaritas. The sight of a pajarita with angular contours and a raised beak reminds me of those three cool and joyous years when I went to bed every night sleepy and woke up with joy every day. My character determined my hobbies, it is doubtless, but they reacted on my character. How quiet, how obedient and submissive a paper pajarita is! Some reams I have consumed in making them. It was born as everything lasting is born, slowly. It was in the beautiful days of the spring of 1874, during the bombing of my village. Something had to do with spending time in the dark, damp fish market that needed daylight, for the only doors open to it had been boarded up with mattresses. We heard nothing but the army, battles, Carlists and Liberals, bombs and assaults and the only thing that happened to us was to make about two hundred sparrows (pajarillos) (in France they are cocottes), train them four deep and simulate combat. A prepared cricket cage served as a lamp, with a match, we called it an electric light, and to the light that so scarce and diminished we were making all the birds go around the table, step by step, while we sang a funeral passage that we had heard. The powerful nations of struggling little paper birds had humble origins in the fish market, the vast empires that dominated the drawers and closets of my house and carried their victorious flag to the last corner of an orchard in Olabeaga. Originally those original birds lived in the wild, without police or hierarchical order, without their name or occupation, without a fixed residence, wandering from here to there, from box to box, and what is more surprising, without females nothing worth it, because this was born later. They were produced autonomously and by spontaneous generation, informed by my hands and those of my cousin, their creators, of the raw material of a white paper. There were two breeds, a slimmer and slimmer, made of two doubles, and a thick, bearded and pocketed, made of three. We were two creators, and this dualism made two people, by necessity enemies, since they were born and lived to fight under that Manichean providence. Militia was their life on earth, thus pleasing their creator and owner. In those early days of the golden age, everyone acted and obeyed the same plan, everyone came from the same role and from the same hands. The individual had not yet emerged from the mass, that was pure objectivism, in serious philosophical terms. Their fights were very simple and inoffensive; they consisted of placing the armies face to face and waiting resigned to the ball of paper with which I swept the ranks of my enemies, and my cousin those of his. They were dark heroes, victims of doom, who fought under the protection of their protective deities, just as Homer's rude heroes fought alongside the walls of Ilion. There were still no poets to sing them, nor had the muse of History reached them. I hardly remember a fixed thing from such remote times. The first historical king was a wax doll imitating a monkey, with his arms and legs movable by means of pins, adorned with blue, red and gold papers. He wore a tricorn and rode a wax horse. This was Monkey I the Wise. The wise thing came as a consequence of the monkey; we knew only those in the collections of wise dogs and monkeys. Monkey I the Wise was succeeded by Amadeus I, made with a head of King Amadeo cut from a seal. This one did nothing remarkable. Heroes of this age were Lage, a figure of an old Frenchman picked up from a box of French matches, on which was read: L’age des esperances. Another was a caricature of Thiers, also of a matchbox, who in time became, under the name of Heredia, a famous physician, author of a treatise on bird anatomy that I will talk about later. *** STORY OF A FEW PAPER BIRDS II (“Bilbao” August 12th, 1888) The news of that remote time, collected by tradition when it lived fresh and recent, were filed in the truthful and punctual account of all this history of which I only have two booklets. Around Mono I, Amadeo, Lage and other strange characters, the paper birds began to gather. Very soon they acquired degrees and honors, and wished to fixate on stable dwellings, rather than for the need for a home and shelter, so that they could organize sieges of strongholds, assaults, and defenses. What is a city for if it is not to be taken? With boxes, pieces of wood and other junk, the removable city was assembled on the table. Thus was born Huleón., Famous for the battle of his name. It was called Huleón because it was built on the oilcloth that covered the table. What a fight that was! What blows of the ball of lead, the terrible ball of lead against the walls of the superb Huleón! Neither the ladder of chopsticks and thread, nor the rain of projectiles were of any use. Not even Bilbao with being Bilbao resisted the Carlists with such boldness. After Huleón Caberonte was born, the name that was given to the new city because of its sound and nothing significant. What shall I say about naval combat, in rafts and ships on a basin full of water? Bounce goes, bounce comes, the one that fell fell and soaked there. When the water was stirred, it poured out and the naumachias had to be suspended by a superior mandate, superior to that of the creators of those brave people. The week was heavy, every day to school on the same street, to repeat the same things; We arrived on Saturday really tired. The joy of Sunday was the rain, the gray sky to be able to stay at home. What a beautiful afternoon for fighting on a rainy afternoon! Nations grew, new pajaritas appeared every day to swell the armies and the excess of evil brought the remedy. And it was this one that occurred to us to make the poor birds mortal, without them eating or drinking it, without having tasted the fruit of the forbidden tree. In and of themselves, they were intrinsically immortal, but to us, their creators, it seemed bland that we had to give up the slaughter and be content with taking them down. That was not funny, what a thing! And by common agreement we designate what would be considered a wound, healed which the combatant returned to the fight, and what would be considered as death. Horrible battles then took place. Armed each of us with his pin, he began to tear the heroic birds of the other, until given a truce to a voice, he proceeded to separate the dead from the wounded and heal them with patches of paper and rubber. What sincere pain to see so many brave combatants killed, with their crest shattered! Instead, it was a delight to put the patch on them, a glorious trophy with which the glorious destiny of such insignificant beings was marked. It turned out that to apply the patch you had to open them, undo their folds, tear their joints, that is, dismember them, all of which is a monstrous anomaly. When has a sick person been seen to dislocate to cure him, to open the canal to close a wound? It was seen, that in that primitive society surgery was very late. Then the idea of curing them without opening anything was born, for which it was necessary to make a cut near the wound, take measurements, calculate the size, shape and folds of the patch, all of which required a careful study of paper-bird anatomy. And here we are inventing names for such a fold and which double, for this angle and the other, extravagant names that were nothing more than those of the human body, in the language of birds. This treatise on anatomy was published in the name of the Thiers caricature. It is to know that they had their language, rather, their languages, one of them Basque; on a whim the others. Immortality had given them insignificance, they were all equal in it. But since they were subjected to the pin of death, some have resisted more than others, full of patches, these shattered in the prime of age, in the first battle, and that is how the individual sprouted from the mass, had his name, his story was more than a number. Their names were whimsical names, some taken from the Araucana, from Ercilla, which we read then to inflame our warlike spirit; and there was Cayuguán, which gave its name to the cayeguanos, Caupolicán, Lautaro, etc. There was also Attila, a giant, as he only needed a sheet of the majors. I knew them one by one, I appreciated their virtues. I will never forget the famous Lunkekwig, a name that I invented for him because it meant nothing and made me sound like barbarian and bombastic with his kas and double vees. He was riddled with pinpricks, and covered with patches, but at last the poor thing died, what a pity! It was one of my biggest sorrows. Death was already regularized, but birth was not, because, frankly, being born by birlibirloque, by spontaneous generation, is a corny thing. So we thought that it was not right for the bird to be alone and we devised a companion similar to him. By raising its beak, the way its legs are made, instead of lowering it, the female was already invented. And from then on we made the birds, we folded their beaks inwards and thus they were placed between the folds of the females until the latter, with the bustle of going and coming back, were released, that is, they gave birth. And there were marriages, civil registry, for those loves, very chaste of course, because there were no more begetters than us; everything was done by our work and grace, and the so-called father served so that the new bird was called "so, son of which." And as a consequence and precedence of the loves there were abductions. That was sinking, these were flashes that announced the irruption of new ideas, the awakening of another life that would destroy the innocent and simple little paper birds. The poor women were not enough to embody my ideas; the love that creates societies destroys them. *** STORY OF SOME PAPER BIRDS III (“Bilbao” August 19th, 1888) But how can I stop counting the inexhaustible wealth of that world? There were laws written in the form of a decalogue, solemnly promulgated and engraved in Greek characters on the lid of the box in which the birds were collected. In addition to the two rival nations, there had to be an irruption of the barbarians, without it we could not conceive of history, and there was, that of the cayeguanos, notable for their barbarism, who after being victorious became civilized. We then read Jules Verne and Captain Mayne Reid, and as a world without animals was bland, we made them out of cardboard, in strange shapes, with large pins for horns, with a fake bead at the end of a thread that served as a tail. others, others with rubber paper chests, and all this so that instead of being provided with pins, pearls, rubber paper and other tools by a prodigal divinity, they would have to hunt them with the danger of their lives. Hunts were organized and carried out on the table. Animals defended themselves with pins. Not all hunted, but the others had money to buy the hunting products, because there were coins that were taken out on paper by rubbing it with a pencil on a small or large dog and glued on both sides with wafer, there were bank notes ... What wouldn't there be? I went to Olabeaga for the summer and led an expedition there, armed to the nines. There, in a corner of the garden they established their colony, clay hovels within a palisade and under a trellis. What a pleasure when it rained and the shacks were damaged, full of mud! I then believed that the greatest pleasure of a sailing is to be shipwrecked; Jules Verne's shipwrecks are so beautiful! Too bad there was no desert island in the garden, and the birds could not die of hunger or scurvy! A heavy rain washed away almost all of them and thus the Olabeaga colony came to a dramatic end. That became more subtle, byzantinizing little by little and a day came when despite everything they were a small body for new ideas and then I left the birds with sorrow. What did those unknown armies do, the joy of my childhood? Where did so many silent and patient heroes go, toys of higher powers? They sprouted from matter when I called them to life, they lived at my will and when, angry with childishness, I threw them into oblivion, they were as resigned as they had come to life. Every time I see or make a paper pajarita, I remember my happy days of the bombing, the germination of my ideas, the slow formation of my spirit and all that living, varied and fresh world that after enriching my fantasy and exciting my intelligence was to die in the dark corner where the child's scorned toys die. Others grew up in the field, running through it, breathing in the air scents of the orchard and hearing the birds of flesh and blood sing; I walk through the streets, breaking boots for them, embodying my ideas in little paper birds and giving them life. I believe in the duty of dedicating this memory, sterile for them, to those who were my childhood companions. Who can swear that in those inanimate, inert and cold pieces of paper there would not be a shadow of conscience? Not me, I've never been a paper bird. When I hear so much nonsense, so much taking it all seriously, so much talking about interiors that are not seen, I remember my obedient and silent pajaritas who lived far from the filth that fools pile up like dung beetles. We men of flesh had to take as a model, not only ants and bees, but also those paper peoples (pueblos de papel), free and obedient, always happy, resigned to life and death, pious towards their creator and animated by the same will. and the same end. I still keep as relics of those times two, the only ones that have been saved, of the booklets in which we kept the annals of those people. ********** |

|||||||