| The Public Paperfolding History Project

Last updated 5/5/2025 x |

|||||||

| The Paperfolding of Akira Yoshizawa | |||||||

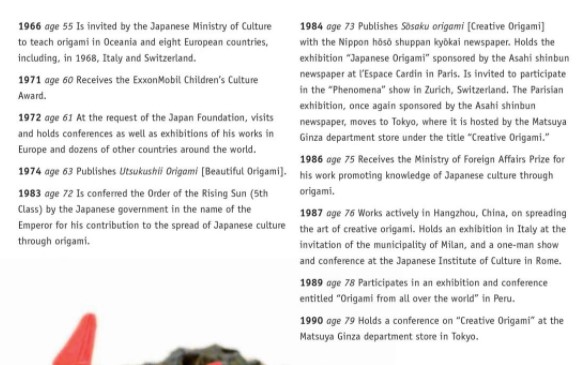

Introduction Akira Yoshizawa was born in 1911 and died in 2005. Much of the information about Yoshizawa's life in the Chronology below is taken from secondary sources which do not identify the original primary source of the information. These secondary sources are not always consistent with each other. Wherever the sources appear to disagree I have generally preferred David Lister's two articles in 'British Origami' which seem to me to be the fullest and probably the most accurate accounts. For this reason much of the information on this page should be treated as provisional and liable to be updated if the primary sources should ever become available. A list of the main sources relied on can be found at the foot of this page. They are referenced within the Chronology in brackets as (DL1) etc. ********** Akira Yoshizawa and Isao Honda Akira Yoshizawa and Isao Honda seem to have known each other well, but it is difficult to discover exactly what their relationship was or when it began. Honda was 23 years older than Yoshizawa. David Lister (in DL1) does not give a specific date for when they first met but clearly places this first meeting in between the publication of Isao Honda's 'Origami Part One' in 1931 and 'Origami Shuko' in 1944. 'During his time in Tokyo ... Yoshizawa came to learn about another paperfolder, Isao Honda, who was a much older man ... Honda was now thinking of publishing a new collection of folds ... Yoshizawa managed to meet Honda and he offered him some of his models ...' Honda claimed that he had been Yoshizawa's teacher. However, for his part, Yoshizawa insisted that these claims were untrue. Engel quotes Yoshizawa as saying 'I never learned from a teacher ... My teacher is nature.' In DL2 David Lister wrote 'Apart from the little girl who folded a boat for him when he was three years old, Yoshizawa did not have any human teacher'. See entry for 1965 below for further details of Honda's claims in his book 'The World of Origami'. ********** Chronology 1911 Akira Yoshizawa was born in Kaminokawa in Tochigi Prefecture in Japan in 1911. According to DL1 'Akira Yoshizawa was born into a typical Japanese farming family ...His father owned a dairy, where he sold milk from a dozen or so cows in his herd, and a small arable farm on which he grew rice and vegetables ... Eleven children were born to the family, but three died in infancy. The survivors were a sister, who was older, and seven surviving sons, of whom Akira was the sixth.' ********** 1914 According to DL1 'Akira was only 3 years old when a young woman, who lived nearby, entertained him by folding a traditional sailing boat.' It seems that his brothers destroyed the boat but Akira succeeded in reconstructing it and 'became a paperfolder for the rest of his life.' ********** 1917 According to DL1 'Akira started school at the age of six. As in many Japanese schools at that time, there were no handicraft lessons in the school and no paperfolding was taught.' It is not clear whether this school was a Froebelian-style kindergarten, but if it was it seems that the syllabus had greatly diverged from Froebel's ideals. According to the biographical information in 'Origami Museum 1' (see entry for 1987) 'His interest in origami began from the time he was a child, when he started to study and create figures.' DL1 says 'Akira continued to fold paper as a private pastime, learning to fold the origami models which were a traditional part of childhood in Japan. But he was not content merely to copy other models slavishly. From the beginning he experimented with the paper, trying to discover new ways in which it could be folded.' ********** 1923 According to DL1 'In 1923, when Akira Yoshizawa was aged thirteen, he left Tochigi alone to go to live in Tokyo, where he obtained a palce in high school.' ********** 1924 According to DL1 'Unfortunately ... he had to leave school after only one year ... he continued to further his education by attending evening classes for a further two years' and 'It was when he was fourteen or fifteen years old that he began ... to create his own successful origami designs.' ********** 1926 According to JGOM, in this year Yoshizawa received a degree from the Taimei Technical Institute in Tokyo. We should probably read 'qualification' or 'qualifications' for 'degree'. I do not know what subject the qualification(s) was / were in. ********** 1928 DL1 says 'After Yoshizawa finished his evening classes in 1928, he continued to study privately. He was very interested in Buddhist philosophy and like many young men, when he was aged seventeen, he entered the Buddhist priesthood for several years. However, he did not take residence in a monastery'. ********** 1932 DL1 says 'In 1932, when he was aged 22, Yoshizawa took employment in a factory which manufactured machine parts' and that. Yoshizawa continued working at the factory until around 1941. ********** 1935 DL1 says 'During his early years, he was taught geometry by his foreman ... after three years he was given the job of instructing the yougf apprentices who entered the factory in the skills they would need for their work' and 'Yoshizawa had the idea that he could make it easier for the apprentices to learn geometry if he taught them by means of origami.... The idea was successful ...' ********** 1938 DL1 says 'In 1938, while still working at the factory, Yoshizawa married for the first time.' According to the biographical information in 'Origami Museum 1' (see entry for 1987) 'His serious work commenced in 1938 when he was employed in a steel mill.' By this time, of course, Japan had already embarked on war, first with Manchuria and then with China, although not yet with Britain or the USA. ********** 1941 DL1 says 'Yoshizawa continued to work at the factory until about 1941, when he became ill and had to give up his work. He also felt that he would be able to devote more time to origami and other paper crafts. However, he still had no intention of making his living from origami. It was a pastime ...'. ********** 1943 DL1 says 'By 1943 his health had recovered sufficiently for him to be called up into the army, although he was given a non-combatant role as a medical orderly. ********** 1944 DL1 says 'In 1944 he was posted to Hong Kong'. ******** Without giving a specific date, but clearly placing the events in between the publication of Isao Honda's 'Origami Part One' in 1931 and 'Origami Shuko' in 1944, DL1 says 'During his time in Tokyo ... Yoshizawa came to learn about another paperfolder, Isao Honda, who was a much older man ... Honda was now thinking of publishing a new collection of folds ... Yoshizawa managed to meet Honda and he offered him some of his models ...' 'Origami Shuko' by Isao Honda was published in 1944 (in Japan in Japanese). It contains a number of designs (see below) that are attributed to Akira Yoshizawa. Most of these are very simple designs. The exceptions are the Hen, Rooster and Chicks, which are pictured but not diagrammed because, Honda says, they both require a level of technique almost impossible to diagram.and are far too complicated for the kind of handicraft education for young people the book is intended to provide. This makes it clear that by this time Yoshizawa's design techniques were already quite advanced compared to traditional folding. In David Lister's Obituary for Yoshizawa (see below), he states 'Many of the models in the book are the traditional folds which are familiar to us from his English books, but there is a section of two-piece models (of the kind which also occupy a large proportion of his English books). Honda steadfastly claimed these as his own, but each one has the name of Yoshizawa printed by it.' The latter stateent is untrue. Only one compound glued design, the Camel, is attributed to Yoshizawa. The designs attributed to Yoshizawa in 'Origami Shuko' are: Hen, Rooster and Chicks *** 'Tanuki no Harazutsumi' (Raccoon-dog Stomach Drum) or 'Bunbuku Chagama' (from a square) *** Container on Legs (from a square) *** Cloak (derived from the traditional box design) (from a square) *** The Wild Goose (from an equilateral triangle) *** Airplane (from an equilateral triangle) *** Nurse's Cap (from an equilateral triangle) *** Frog (from an equilateral triangle) *** Pigeon (from an equilateral triangle) *** Hexagonal Flower Shape (from an equilateral triangle) *** Sailboat (from a right angle isosceles triangle) *** Geese (two designs) (from right angle isosceles triangles) *** Cormorant (from a right angle isosceles triangle) *** Module in the shape of a 120 / 60 rhombus (from a 120 / 60 rhombus) *** Lion Dance (from a 120 / 60 rhombus) *** Camel (from two squares glued together) ********** 1945 DL1 says 'Yoshizawa himself fell ill and in 1945, before the war was over, he was returned to Tokyo, where for a while he remained convalescent' and 'After being discharged from the army, Yoshizawa returned to live at Tochigi and remained there for five years.' ... 'To make a living, Yoshizawa did whatever jobs were available. He worked in a friend's restaurant, or went round people's homes selling 'tsukudani.' ... 'it was during this time that he suffered the death of his first wife'. According to DL7 'Tsukudani is a delicacy made by simmering a broth of soy sauce, sake and sweet cake containing dried tuna, clams, seaweed or small fish until the liquid has been completely reduced.' ********** 1950 DL1 says 'in 1950 ... The Teacher's Union planned to hold an exhibition of arts and crafts at the ... Utsunomiya Educational Hall ... Yoshizawa was invited to put on a display in one corner ... Yoshizawa obviously made a good impression, for he was later invited to give a public lecture on the basic theory of educational Origami at the national Convention of the Japanese Teacher's Union'. Subsequently Yoshizawa returned to Tokyo 'to try again to make origami his career.' (There is an inconsistency here. See entry for 1941.) ********** 1952 Publication of an article about Yoshizawa's design work in the magazine Asahi Graf of 9th January 1952. DL 1 says 'Unexpectedly, Yoshizawa's fortunes changed ... Tadasu Iizawa ... the editor of a Japanese picture magazine called 'Asahi Graf' (had the) 'idea of publishing a feature on origami in the magazine. The subject would be the twelve signs of the Japanese zodiac ...' and 'Yoshizawa's twelve Signs of the Zodiac appeared in the issue ... for January 1952 and they were an immediate sensation ... it was the turning point of his career. Tadasu Iizawa ... took Yoshizawa under his wing ... by putting his name forward and seeking introductions for him.' ********** This led to publication of a series of articles on the work of Yoshizawa in the issues of 'Fujin Koron' (Ladies’ Opinion) magazine for April to December, 1952 which, according to DL1 'consolidated Yoshizawa's reputation.' ********** 1953 According to David Lister writing in 'The Art of Akira Yoshizawa' (see below) Gershon Legman managed to establish contact with Yoshizawa by letter in this year. ********** 1954 Publication of Yoshizawa's first book, 'Atari Origami Geijuitsu' (New Art of Origami). There is no claim in the book that the designs are Yoshizawa's own but this seems likely in most cases. Almost all of them are folded from square paper and are pure origami in the sense that no cuts are used, although there is one compound design which is glued together. Yoshizawa added an English introduction to the book at a slightly later date (exact date not known). Yoshizawa's original Afterword (in Japanese) mentions Gershon Legman: ''One thing I would like to mention is the friendship I have with Professor G. Legman of New York. He is an enthusiastic researcher of origami, which is rare for a foreigner, and as I have exchanged opinions with him about the history of origami, I have come to feel more confident about the spread of origami around the world. In a recent letter, he, who is now in Paris, encouraged me to translate and publish my book in English, French, and Spanish, and also to launch a world peace movement through origami as one of the projects of UNESCO and the International Red Cross.' (Note that Legman was not entitled to the title of Professor.) The First Foreword, written by Tadasu Iizawa, the Editor of the Asahi Graf newspaper says, inter alia, roughly translated: 'At present, he doesn't have a particular job and makes a living from origami, so it seems that his life is pretty tough, but he says, "If it comes down to it, I'll just start selling tsukudani again." Since I'm the one who introduced him to the world of journalism, I feel a strong sense of responsibility, but there are already researchers from outside Japan who have come to learn from him, so I am very pleased that his art will be further recognised with this new book.' ********** According to JGOM, in his year, Yoshizawa 'Participates in the seminar 'The Arts and Crafts in General Education and Community Life' organised by UNESCO in Tokyo'. DL1 says that he presented a paper titled 'Origami Based on Free Expression'. ********** Also in 1954, according to DL1, Yoshizawa established his own origami society, called the International Origami Study Society. ********** 1955 According to DL1, in this year, Yoshizawa 'had the honour of being invited to contribute an article on origami for an encyclopaedia in the Japanese language.' ********** Yoshizawa also held his first 'full-scale public exhibition ... in the centre of Tokyo in the Ginza, which is the city's main shopping centre ... the sponsors of the exhibition were ... Tokyo Electric Power'.. ********** According to DL2 'When Gershon Legman heard about Yoshizawa's exhibition in the Ginza ... his immediate reaction was to suggest that it should be brought to the West. Yoshizawa was reluctant at first but then sent ... not only the folds from the exhibition ... but also further models which he had specially folded'. Legman initially arranged 'a small preliminary exhibition of some 300 ... folds on tables under the trees in the garden of a friend who lived in Cagnes sur Mer'. Later, in October 1955 a more formal exhibition was arranged at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. According to DL2 'Legman was in attendance at the Museum and taught simple models.' David Lister also states in DL2 that this 'Amsterdam exhibition did not have a very great impact outside Holland.' An article about the exhibition appeared in the Dutch magazine Goed Nieuws on 17th December, 1955. According to DL5, 'The 1955 Exhibition By Akira Yoshizawa', 'The exhibition was honoured with a visit by Japanese Ambassador to the Netherlands, Suemasa Okamoto. He was very impressed and afterwards sent a report to the Japanese government. He also wrote to Yoshizawa an enthusiastic handwritten letter praising the exhibition of his work. The ambassador sent Yoshizawa copies of articles that were printed in the newspapers and magazines. Yoshizawa was deeply moved when Suemasa Okamoto told him that after the ill-feelings brought about by the War, the exhibition had helped to foster a better relationship between the Netherlands and Japan. It was probably this report that led to Yoshizawa being sent on later missions to many countries of the world as an ambassador for Origami and Japanese culture.' ********** By this time Gershon Legman was also in touch with the stage illusionist Robert Harbin and 'wrote to him at length about Akira Yoshizawa and the exhibition of his work in Amsterdam. It was just in time for Harbin to include the information in his book 'Paper Magic' which was published in the following year'. ********** 1956 In this year Yoshizawa married his second wife, Kiyo. ********** Publication of 'Paper Magic' by Robert Harbin which included the following information about Yoshizawa and his designs.

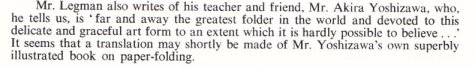

According to DL2 Lillian Oppenheimer was sent a copy of this book and thus first learned about Yoshizawa. ********** 1957 Issue of Yoshizawa's book 'Origami Dokuhon' by the publishing house Ryokuchi-Sha. *********** According to the biographical information in 'Origami Museum 1' (see entry for 1987) 'Exhibitions were held in 1957 in Tokyo and Yokohama. After that he exhibited in many other cities in Japan'. ********** 1957 also saw the publication of articles on the work of Yoshizawa in 'Shufu no Tomo' (Young Ladies’ Friend) magazine. According to DL1 'This association continued for several years.' ********** 1958 On 27th April 1958 The Star Magazine, the Sunday supplement of the Washington Evening Star newspaper, published an article featuring Yoshizawa which pictures designs he has created from paper money. The article gives no context about how it came to be sourced or published. ********** On 27th June 1958 Meyer Berger's 'About New York' column in the New York Times featured Lillian Oppenheimer and her love of paperfolding. The column was titled 'Origami, the Ancient Art of Paper-Folding, has Gramercy Square Disciple.' It mentions Yoshizawa several times:

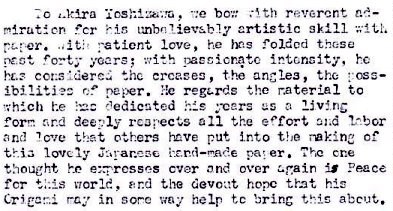

*** Volume 1, Issue 1 of the Origamian, which was published in October 1958, contains a eulogy to Yoshizawa written by Lillian Oppenheimer:

'To Akira Yoshizawa we bow with reverent admiration for his unbelievably artistic skill with paper. With patient love, he has folded these past forty years with passionate intensity, he has considered the creases, the angles, the possibilities of paper. He regards the material to which he has dedicated his years as a living form and deeply respects all the effort and labour and love that others have put into the making of this lovely Japanese hand-made paper. The one thought he expresses over and over again is Peace for this world, and the devout hope that his Origami may in some way help to bring this about.' *** The same issue also contains an excerpt from a letters from Gershon promising to send 'on loan all the exhibition foldings of Mr Y's I still have' for display at the Cooper Union and:

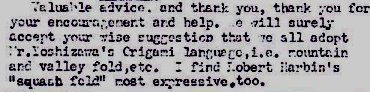

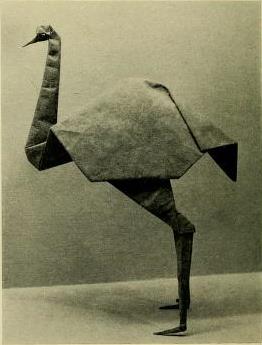

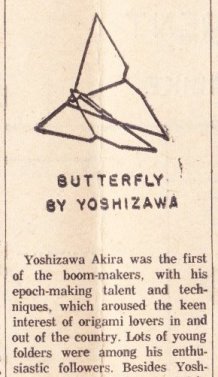

********** 1959 Volume 1, Issue 4 of the Origamian, which was published in January 1959, mentions that 'Akira Yoshizawa enclosed a newspaper clipping showing three new Xmas Origami creations'. *** Articles on the work of Yoshizawa appeared in Fujin Koron (Ladies’ Opinion) magazine January to September 1959. *** Volume 1, Issue 5 of the Origamian, which was published in March 1959, contains diagrams for Yoshizawa's 'Butterfly' and mentions that Lillian Oppenheimer is intending to go to Japan to meet him. *** Lillian Oppenheimer briefly visited Yoshizawa at his Tokyo home. *** A selection of Yoshizawa's paperfolds from the 1955 Stedelijk Museum exhibition, and, according to David Lister writing in 'The Art of Akira Yoshizawa' (see below), other designs which Yoshizawa sent direct, featured in the 'Plane Geometry and Fancy Figures Exhibition' at the Cooper Union Museum in New York, held in Summer 1959. The exhibition catalogue lists 43 Yoshizawa designs but contains a photo of just one, an ostrich.

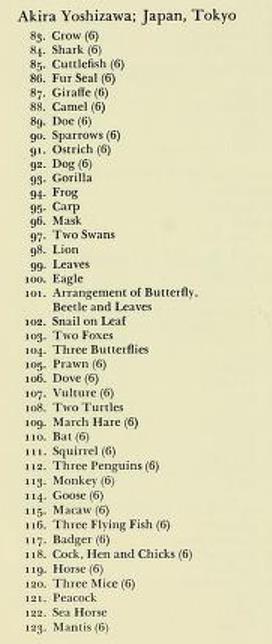

Those designs marked (6) in this list were designs that had previously been sent to Gershon Legman and exhibited in Amsterdam in 1955. ********** These photographs of penguins and a squirrel by Yoshizawa appear in an article in The Ottawa Citizen of 15th August 1959.

********** According to Robert Lang, writing in JGOM, Yoshizawa completed the design of his Cicada, folded from a complex multiple bird base, in this year. ********** 1960 This cartoon of Yooshizawa appeared in The Washington Observer of 9th July 1960.

********** 1962 Publication of 'Origami Tehon' by the International Origami Research Society. According to David Lister (See The Books Of Akira Yoshizawa British Origami) this small booklet was supplied by Yoshizawa alongside packets of paper that he sold and was not sold separately. ********** According to Robert Lang, writing in JGOM, Yoshizawa shared a photograph of his Cicada and its folding plan with Gershon Legman during this year. ********** 1963 Publication of 'Tanoshii Origami' (Joyful Origami) and 'Origami Ehon' (Origami Picture Book) by Froebel Kan Co. Ltd. According to the biographical information in 'Origami Museum 1' (see entry for 1987) 'He won the Mainichi Culture Award for Publication for 'Tanoshii Origami'. ********** An adaptation of a Jumping Frog by Yoshizawa appears in 'The Folding Money Book' by Adolfo Cerceda which was published by The Ireland Magic Co in Chicago in 1963.

********** Yoshizawa's Butterfly appears in 'Party Lines' by Robert Harbin, which was published by the Olbourne Book Co in London in 1963.

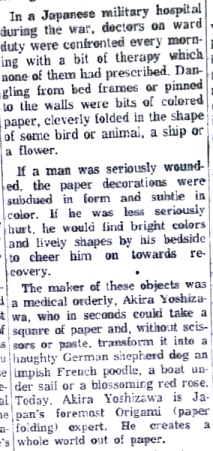

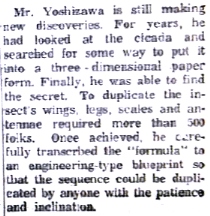

********** Vol 3: Issue 3 of the Origamian for Autumn 1963 contains a profile of Akira Yoshizawa, reprinted from the Asia Magazine (no date of publication given). Excerpts below:

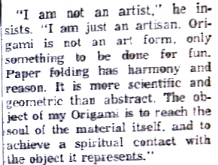

It is worth noting that what he is quoted as saying in this article (excerpt on the right) contradicts what he says in the article below. In one origami is not an artform. In the other it is. *** The same issue also contains an article by Akira Yoshizawa on 'Creative Origami', which was originally published in Kokusai Bunka magazine in January 1961. This article is divided into four sections, 'How Origami Developed', 'Some Ancient Origami', 'Origami Today' and 'Creative Origami'. 'How Origami Developed' sets out Yoshizawa's understanding of the history of paperfolding in Japan. 'Some Ancient Origami' gives examples and sources to back this up, including:

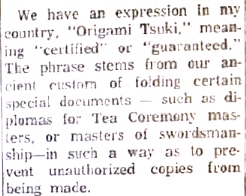

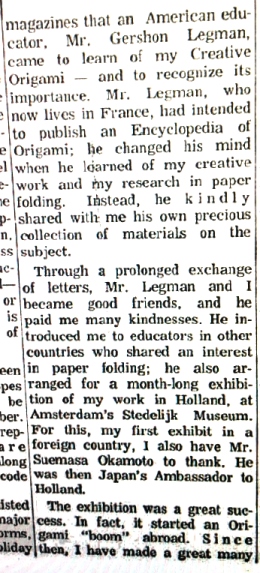

'Origami Today' is a Yoshizawa-centric version of how paperfolding has developed in recent times. It includes mention of his interaction with Gershon Legman:

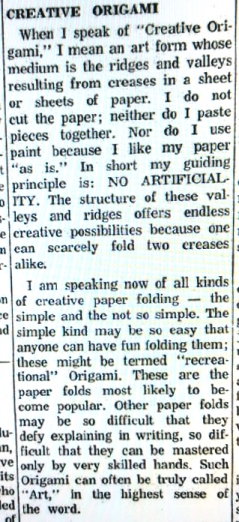

In 'Creative Origami' Yoshizawa's explains his approach to paperfolding as an artform. The whole thing is well worth reading ut these two (non-consecutive) excerpts seem to me to sum up what it is that he is saying:

*** And diagrams for four of Yoshizawa's designs: Mushroom / Puppy / Penguin / Stork. (No titles are given in the original)

********** 1964 Vol 4: Issue 2 of 'The Origamian' for Summer 1964 contains a report of 'A Paperfolder's Trip to Japan' by Florence Temko, which describes her meeting with Yoshizawa:

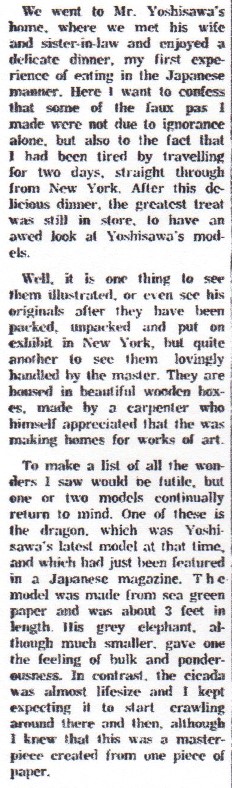

*** Robert Harbin's 'Secrets of Origami', published by Oldbourne Book Company in London in 1964, contained information about Yoshizawa and a picture of a version of his Compound Monkey from 'Origami Dukuhon'.

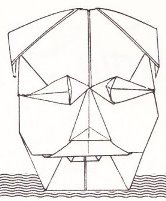

It also contained an Everyman Mask, said to be folded by Adolpho Cerceda, after Yoshizawa. The inclusion of this design was to cause some controversy. See entry for 1969 below.

********** 1965 'The World of Origami' by Isao Honda, which was published in the USA by Japan Publications Trading Company in 1965, contains diagrams for a module folded from a rhombus, and attributed to Yoshizawa, which will make 'Rhombus Constructions', ie 3, 4 and 5 sided pyramids with open bases. (This module was previously published in 'Origami Shuko'.)

The book also contains information relating to the relationship, and indeed it seems rivalry, between Honda and Yoshizawa. There are several places in which Honda claims to have originated the idea of folding compound figures and that certain compound designs, the peacock, horse, cat, monkey etc from two squares and the giraffe, alligator and three monkeys, from two equilateral triangles and rhombuses, are his own designs. The 'etc' presumably means that Honda is also claiming to be the designer of the other compound figures listed on page 130 as well. (from the biographical notes on the dust jacket)

From p261

From p252

While Honda claims Yoshizawa as his pupil (from the biographical notes on the dust jacket)

and promotes Yoshizawa's book 'Origami Dokuhon', he also, on several occasions, denigrates Yoshizawa's creative work: From p292

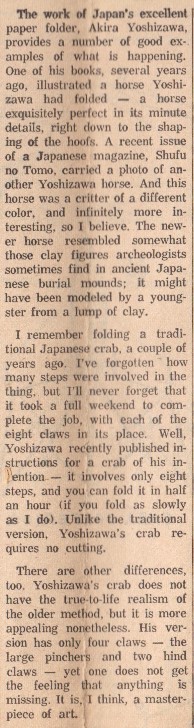

********** Vol 5: Issue 3 of 'The Origamian' for Autumn 1965 contained an article titled 'The New Trend' by Peter Van Note, discussing designs of 'a highly sophisticated sort of simplicity' now being produced by Japanese designers. Here is what he has to say about Yoshizawa:

********** 1966 According to the biographical information in 'Origami Museum 1' (see entry for 1987) 'From 1966 to 1984, under the auspices of the Foreign Ministry and the Japan Foundation, Yoshizawa visited Australia, New Zealand, Europe, South East Asia and Central America, a total of over 30 countries, as lecturer and teacher of origami'. Some details of his visit to Canberra are recorded in an Article about Yoshizawa in The CanberraTimes, February 1966, which also states that he will visit Sydney and Melbourne. There are also some photographs in The Canberra Times taken on 22nd February 1966 According to JGOM Yoshizawa 'Is invited by the Japanese Ministry of Culture to teach origami in Oceania and in eight European countries, including, in 1968, Italy and Switzerland. Many of Yoshizawa's designs feature in the film 'Origami: The Folding Papers of Japan' which was made by the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 1966, presumably as part of the same cultural outreach program. 'Akira Yoshizawa: Japan's Greatest Origami Master' published by Tuttle in 2016 contains a description by Horoko Ichiyama of how Yoshizawa was invited to a party to celebrate the opening of the Reader's Digest building in Japan and how he folded pegasus's as the centrepiece of each of the 17 tables. ********** 1967 Publication of Second Edition of 'Origami Dokuhon 1' by Kamakura Shobo. (An English language version of the text only of this book was published as 'Creative Origami' and supplied to English speaking purchasers.) ********** Vol 7: Issue 3 of 'The Origamian' for Autumn 1967 contained an article by Toshie Takahama entitled 'Origami in Japan Today' in which Yoshizawa is mentioned.

********** 1968 Vol 8: Issues 1 and 2 of 'The Origamian' for Spring and Summer 1968 contained a profile of Ligia Montoya, 'Ligia Montoya: Woman and Artist', written by Gershon Legman, which contained mention of Yoshizawa's view of three-legged animals and of Ligia Montoya.

********** 'Teach Yourself Origami: The Art of Paperfolding' by Robert Harbin, which was published by The English Universities Press in 1968, included diagrams for Yoshizawa's 'Pigeon'.

********** 'Your Book of Paperfolding' by Vanessa and Eric de Maré, which was published by Faber and Faber in London in 1968, included a 'Mask' said to be 'after Akira Yoshizawa, Japan', although it bears little resemblance to Yoshizawa's original design.

********** 1969 Publication of English language versions of 'Tanoshii Origami' and 'Origami Ehon' as 'Origami Volume 1: Fun with Paperfolding' and 'Origami Volume 2: Fun with Paperfolding' respectively. ********** 'The Origamian' of Summer 1969 contains a letter from Robert Harbin which explained that Yoshizawa had complained that about the inclusion of three designs in his 1963 book, 'Secrets of Origami'.

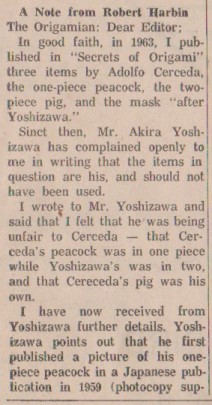

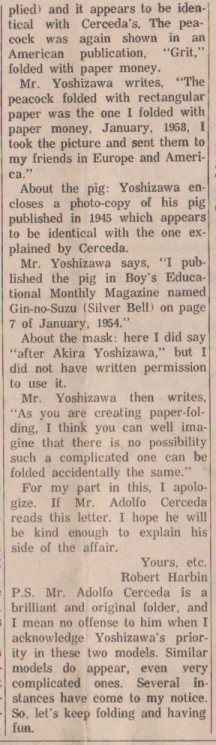

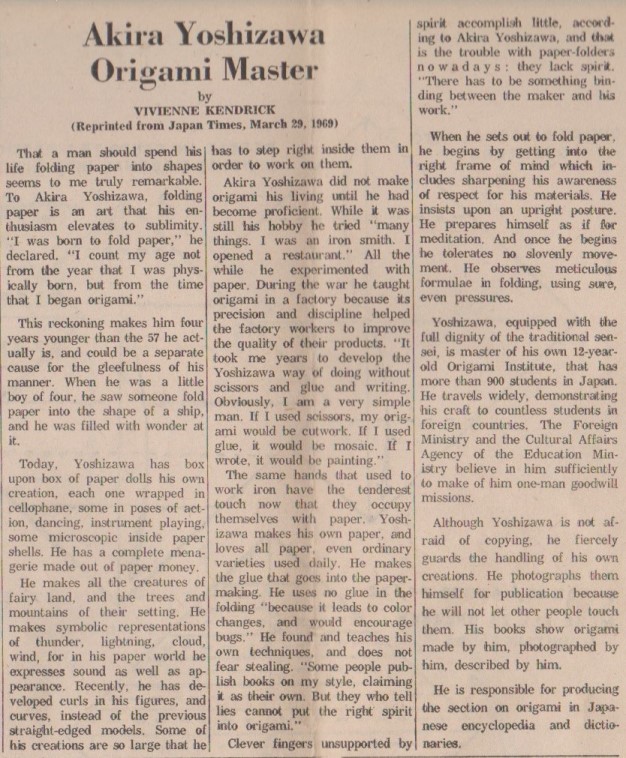

*** The same issue also contained an article, 'Akira Yoshizawa Origami Master', by Vivienne Kendrick, reprinted from the Japan Times of March 29th 1969.

********** Vol 9: Issue 3 of 'The Origamian' for Autumn 1969 contained a letter from Adolpho Cerceda responding to Robert Harbin's letter in Volume 9, issue 2.

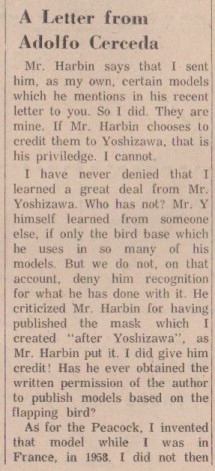

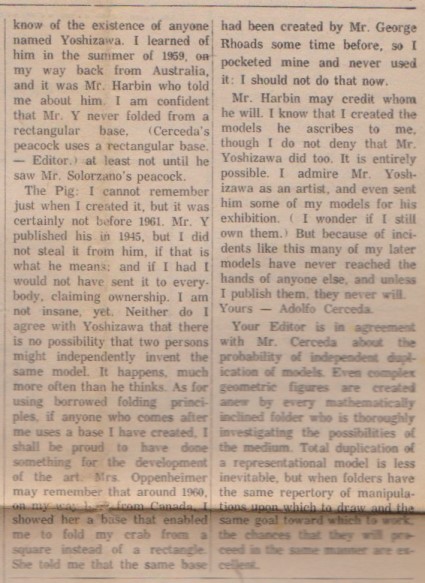

********** 1969 Vol 9: Issue 4 of 'The Origamian' for Winter 1969 contains a letter from Samuel Randlett commenting on Adolpho Cerceda's letter in Vol 9, issue 3.

********** 1970 A photograph of Yoshizawa's 'Sparrow' appeared in an article by Robert Harbin in Woman's Own magazine of March 1970.

********** 'Simple Origami' by Eric Kenneway, which was published by The Dryad Press in Leicester in 1970, contains diagrams for a Flapping Dove by Akira Yoshizawa.

********** The August 1970 edition of Reader's Digest, p196 on, contained an article written by Leland Stowe, titled 'Paper Magic of Origami' which included information about Yoshizawa and his creations. According to JGOM this article was translated into 13 languages and distributed around the world. ********** 1971 According to the biographical information in 'Origami Museum 1' (see entry for 1987) 'He received the Mobil Children's culture Award in 1971'. ********** In the 1971 Octopus Books edition of 'Secrets of Origami' by Robert Harbin, the original text relating to the Novelty Purse has been altered from just 'Origin: Japan ' to 'Origin: Japan. Akira Yoshijawa.' (sic). I do not know what the evidence for attributing the design to Yoshizawa is.

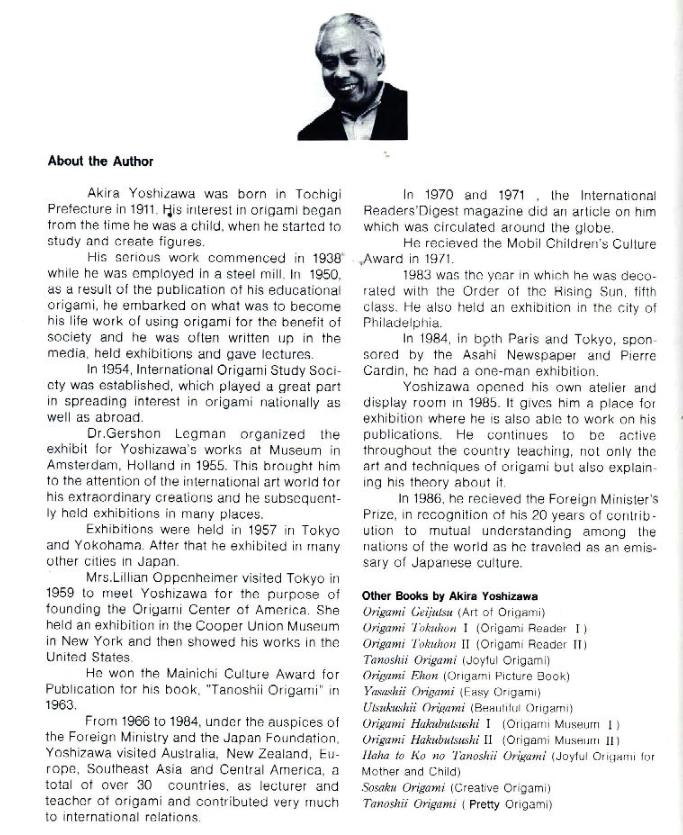

********** 1972 According to JGOM 'At the request of the Japan Foundation, visits and holds conferences as well as exhibitions of his work in Europe and dozens of other countries throughout the world.' ********* 1974 Publication of 'Utsukushii Origami' (Beautiful Origami) ********** 1978 Publication of 'Origami 1'. Publisher unknown. David Lister mentions that it seems as though an 'Origami 2' was planned but possibly never published. ********** Republication of 'Tanoshii Origami' and 'Origami Ehon' in expanded editions by Kamakura Shobo. ********** Publication of 'Yasashii Origami' (Easy Origami) by Kamakura Shobo as a companion volume to 'Tanoshii Origami' and 'Origami Ehon'. ********** 1979 Publication of 'Origami Hakabutsuchi 1' (Origami Museum 1 - Animals), 'Origami Hakabutsuchi 2' (Origami Museum 2 -Seasons and Traditional Japanese Events) and 'Haha To Ko No Tanoshii Origami' (Joyful Origami for Mother and Child) by Kamakura Shobo. ********** 1983 Publication of 'Antologia di Origami - Animali' an Italian translation of 'Origami Hakabutsushi 1' by Il Castello of Milan. According to the biographical information in 'Origami Museum 1' (see entry for 1987) '1983 was the year in which he was decorated with the Order of the Rising Sun, fifth class. He also held an exhibition in the city of Philadelphia. ********** 1984 Publication of 'Sosaku Origami' by Nippon Hoso Kyokai. According to the biographical information in 'Origami Museum 1' (see entry for 1987) 'In 1984, in both Paris and Tokyo, sponsored by the Asahi Newspaper and Pierre Cardin, he had a one man exhibition'. ********** Publication of 'Tanoshii Origami'. Publisher unknown. David Lister states that to distinguish this book from previous books with the same title it is sometimes known as 'Tanoshii Origami (Koala Book)' ********** 1986 Publication of 'Origami Dukohon 2' by Kamakura Shobo. According to the biographical information in 'Origami Museum 1' (see entry for 1987) 'In 1986 he received the Foreign Minister's prize in recognition of his 20 years of contribution to mutual understanding among the nations of the world as he travelled as an emissary of Japanese culture'. ********** 1987 Publication of 'Origami Museum 1' a translation into English of the unaltered text of 'Origami Hakabutsushi' with an added introduction by Lillian Oppenheimer and a short outline of Akira Yoshizawa's life. The information from this page has been incorporated in this chronology.

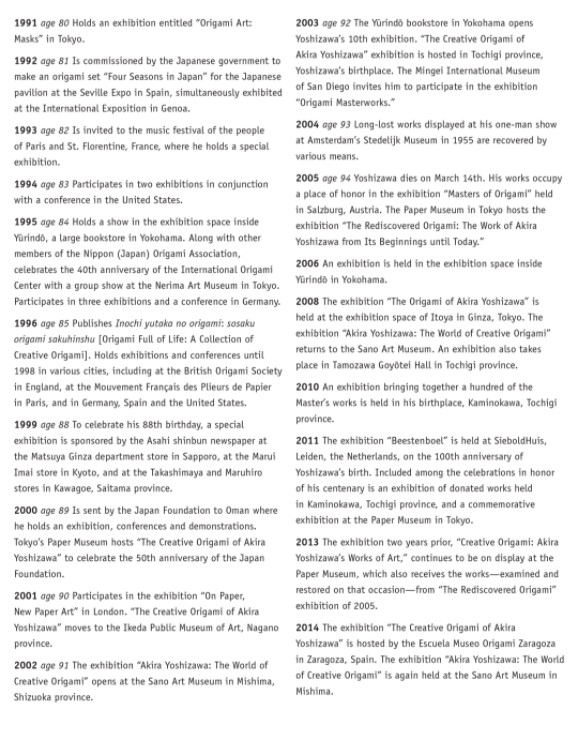

********** 1988 Works by Yoshizawa were included in the Paris Origami exhibition in March 1998 which was held in the Carrousel du Louvre. ********** 1996 Publication of 'Inochi Yutaka Na Origami' (Lively Origami) by Sojusha Inc ********** 1998 Publication of diagrams for two simple Pinwheels (one from a square and one from an equilateral triangle) in British Origami magazine, issue 192 of October 1998, alongside the first of David Lister's articles on Yoshizawa's life (DL1). ********** 1999 Publication of diagrams for a Parrot in British Origami magazine, issue 194 of January 1999 (this was an editor's error for February 1999), alongside the second of David Lister's articles on Yoshizawa's life (DL2). ********** Exhibition of Yoshizawa's paperfolds at the Ginza, Tokyo in October 1999 to mark his 88th birthday (a particularly auspicious birthday in Japanese culture). The exhibition then went on tour to Kyoto and elsewhere in 2000. David Lister's article 'The Art of Akira Yoshizawa' (see above) is largely a description of the contents of this exhibition. ********** Publication of 'Origami', in David Lister's words 'primarily a splendid collection of coloured photographs of Yoshizawa’s models to accompany the great exhibition of his work held in the Ginza'. ********** 2005 Akira Yoshizawa died on Monday, 14th March, 2005, on his 94th birthday. ********** 2016 'Akira Yoshizawa: Japan's Greatest Origami Master' published by Tuttle in 2016 (JGOM) contains a three page biography of Akira Yoshizawa's paperfolding achievements. Where deemed appropriate entries from this biography up to 1972 have been carried over into the chronology above.

********** Sources 'The Origamian' of Summer 1969 contains an article by Vivienne Kendrick titled 'Akira Yoshizawa Origami Master' which is 'Reprinted from Japan Times, March 29th 1969'. It is not clear to me whether this is a translation or whether the original article was in English. The same issue also contains a letter from Robert Harbin about the Adolpho Cerceda controversy. ********** The British paperfolding historian, David Lister, wrote a number of articles about Yoshizawa and his work, which are listed below. The information in these articles probably comes from personal conversations or private correspondence. 'Akira Yoshizawa: Part 1 - His Early Life and Struggle for Recognition in Japan', published in 'British Origami' issue 192 of October 1998. (DL1) 'Akira Yoshizawa: Part 2 - Yoshizawa becomes known in the West', published in 'British Origami' issue 194 of January 1999. (DL2) 'A list of books by Akira Yoshizawa' compiled by David Lister, 1996 / 1997 / 2006. (DL3) 'The Art of Akira Yoshizawa' written by David Lister, an account of Yoshizawa's exhibition in Kyoto in 2000. (DL4) 'The Exhibition of Paperfolding By Akira Yoshizawa in Amsterdam 1955' written by David Lister, 2005. (DL5) Obituary 'A Tribute To Akira Yoshizawa' written by David Lister, 2005, and 'Akira Yoshizawa' another brief summary, undated but written earlier. (DL6 and DL7) Article 'The Making of a Paperfolder: Akira Yoshizawa' by David Lister in 'Masters of Origami at Hangar 7', Hatje Kantz, 2005. (DL8) ********** Akira Yoshizawa's book 'Origami Museum 1', published in 1987, contains a page of biographical information (see entry for 1987 above). 'Akira Yoshizawa: Japan's Greatest Origami Master' published by Tuttle in 2016. (JGOM). A limited preview of this book can be found online here. The designs in this book are from 'Utsukushii Origami', published in 1974, and 'Yasashii Origami', published in 1978, both originally in Japanese, with additional introductory material by Kiyo Yoshizawa, Robert Lang (mainly about Yoshizawa's Cicada) and Horoko Ichiyama. See entry for 2016 for biographical information contained in this book. ********** 'Folding the Universe' by Peter Engle, published by Vintage Original in 1989, sections 'I meet the master' and 'A zen philosophy', a description of a visit to Yoshizawa's home by the author. This is probably the best written portrait of Akira Yoshizawa we have (at least in English) but it is not particularly useful in establishing a chronology. ********** |

|||||||

.

.