| The Public Paperfolding History Project

x |

|||||||

| Japanese Paperfolding until 1970 - An Overview | |||||||

| This

page provides an overview of evidence relating to the

history of paperfolding within Japan. Western-style

kindergarten education, including elements of

paperfolding, was imported into Japan from 1876 onwards.

This date is thus a watershed in the history of

paperfolding in Japan. It may be useful to give the dates of the various recognised periods of Japanese history for reference here: Nara and Heian Periods (710-1192) Kamakura Period (1192-1333) Muromachi Period (1338-1573) Azuchi-Momoyama Period (1573-1603) Edo Period (1603-1868) Meiji Period (1868-1912) Taisho and Early Showa Period (1912-1945) ********** This page is under construction at present ********** Japanese paperfolding before 1876 ********** Japanese paperfolding after 1876 The import and adaptation of Froebelian paperfolding designs and ideas In the early Meiji period, from 1868 onwards the Japanese government became interested in kindergarten style education. In around 1871, Shinzo Seki, a teacher of English at the Tokyo Women’s Normal School (now Ochanomizu University), translated several kindergarten manuals into Japanese, among them 'The Kindergarten' by Adolf Douai (1) and 'Moral Culture of Infancy and Kindergarten Guide' by Mrs Horace Mann and Elizabeth P Peabody (2) (although I do not know whether the latter was a translation of the first or second editions). Both of these books make some mention of paperfolding but neither place much emphasis upon it or give any illustrations of folding methods or finished folds. Source (2) also says that Shinzo Seki 'translated a three-volume book on the kindergarten in 1872'. I have not been able to identify which work this statement refers to. Two other Froebelian books, 'A Practical Guide to the English Kinder Garten' by Joh and Bertha Ronge, published in 1855, and 'Der Kindergarten' by Hermann Goldammer, published in 1869, are also said to have been influential in early kindergarten education in Japan, but I do not know if they were similarly translated into Japanese, and, if so, by whom. The first Japanese kindergarten was established at the Tokyo Women’s Normal School in 1876. The 'superintendent' of this kindergarten was Shinzo Seki and the 'head teacher' was Clara Zitelmann Matsuno, a trained German kindergarten teacher, who was married to Hazama Matsuno. Hazama had met Clara while accompanying Prince Kitashirakawanomiya on his studies abroad and it is possible that it was he who had suggested that she undertook kindergarten training before joining him in Japan. There were also two trainee kindergarten teachers, Fuyu Toyoda and Hama Kondo, who worked together with Clara and followed her guidance, although, since Clara could not speak fluent Japanese, her instructions and explanations had to be translated for them to understand.

Clara Matsuno, Fuyu Toyoda and Hama Kondo playing the Pigeon's Nest game with Ochanomizu University Kindergarten children. ********** Two years later, in 1878, the Tokyo Women’s Normal School published ''Yochien Ombutsu No Zu' (Illustrations of Kindergarten Gifts) which contained illustrations of both Forms of Life and Forms of Beauty. The Forms of Beauty were redrawn from 'Der Kindergarten' by Hermann Goldammer (thus evidencing the influence of this book). The Forms of Life were a mixed collection of Western European paperfolds (some found in 'Der Kindergarten' and some not) and specifically Japanese designs such as the Kabuto, the Kikuzara, the Fox Face, the Sanbo, the Paper Crane and the Blow-up Frog. This clearly shows that the occupation of paperfolding was being given a place in the kindergarten curriculum of Shinzo Seki's school. It also, however, shows that the detail of the paperfolding curriculum had been quickly Japanised. ********** Similarly, in Shinzo Seki's 'Yochien Ho Niju Yuki' (Twenty Joys of Play in Kindergarten), which was published in 1879, and which contains drawings of children sitting at tables engaged in various kindergarten occupations, while the illustration relating to the folding of paper strips (verschnuren) shows a form familiar from Western European manuals, that relating to paperfolding per se per se shows a Paper Crane, a Noshi and what appears to be a windmill base with the front flaps folded in half outwards, which is possibly a Hanabishi. No Western European form is in evidence here.

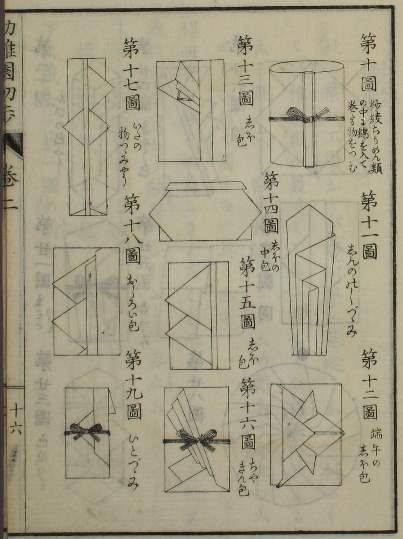

********** The trend towards the Japanisation of kindergarten paperfolding activities is further evidenced in 'Kindergarten Shoho' (Preliminary Kindergarten) by Iijima Hanjuro, which was published in 1885. Here again the section relating to paperfolding per se gives a mixture of Western European and Japanese designs, some of which are Forms of Life (whether traditional or newly invented is hard to discover in some cases) but others of which are traditional tsutsumi (wrappers). Many of these forms are quite complex to fold. There are no illustrations of Forms of Beauty in this book.

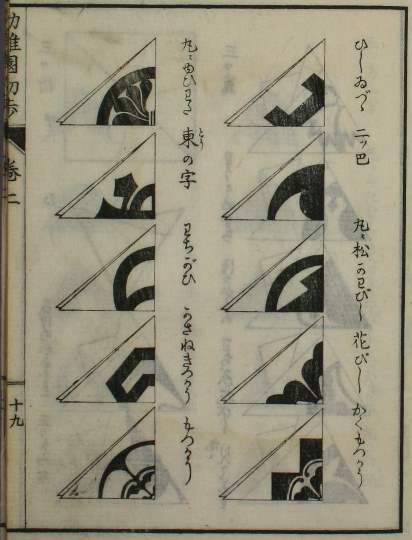

There are also a number of pages explaining how to cut out symmetrical designs for Japanese family crests or mon, a traditional Japanese activity for children which seems to have replaced the Froebelian occupation of Ausschneiden und Aufkleben (Cutting Out and Mounting) within the curriculum.

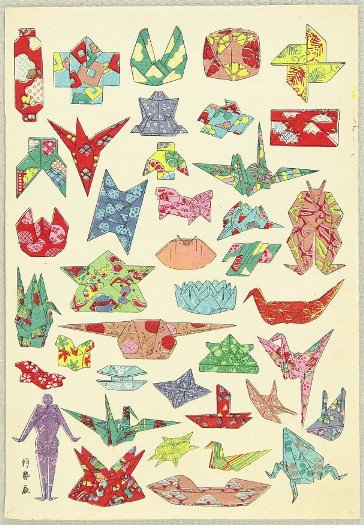

********** Between 1893 and 1896 several Japanese children's magazines seem to have regularly published articles explaining simple origami designs, such as the Sanbo and the Boat with Sail, showing both that by this time paperfolding was seen as a suitable recreation for children but also that these simple designs were not already so well known as to make articles explaining them unnecessary. ********** The early years of the 20th Century saw the publication of a number of kindergarten manuals which contained sections about paperfolding. Although the designs featured in each manual vary somewhat, overall it seems that a definite set of designs considered suitable for use in kindergarten education has emerged. These are still a mix of Western European and Japanese designs, including tsutsumi, but, although some complex designs are still included, they seem, in general, to be simpler than those designs featured in earlier Japanese works. The earliest example, and one of the best, of these manuals, as far as its paperfolding content is concerned, is 'Jinjo Kouto Shogaku Shuko Seisakuzu' (Handicrafts for ordinary higher elementary schools) by Hideyoshi Okayama, which was published in 1903. ********** Many of the designs which appear in these manuals can also be seen in this monozukushi-e print (by an unknown artist), which probably dates to the late Meiji period.

********** Isao Honda In 1908, Isao Honda, who was subsequently to become a prolific author of books about paperfolding, travelled to Europe to study painting, which he did in both London and Paris. Sometime later, after his return to Japan, he wrote his seminal work 'Origami', which was published in two parts, an 'upper' part, usually known as Part One', which was published in 1931, and a 'lower' part, usually known as 'Part Two’, published in 1932. Full details of the contents of Part Two have not yet appeared in the West. Part One contains diagrams for 81 designs in all. Some of these are designs that had previously appeared in other Japanese books, including the kindergarten manuals, or magazines, some are Western napkin-folds, while a few are completely new. In many cases, because of the time Isao Honda had spent in Europe, we cannot be certain whether these previously unknown designs are from the Japanese or Western European traditions, or, indeed, are of Isao Honda’s own invention. What does seem clear, however, is that, although in places this work draws from kindergarten materials, it is intended to be a book of recreational paperfolds, that is paperfolds that are recorded in order that other people can enjoy folding them for themselves.

********** Michio Uchiyama While Isao Honda had been collecting designs for publication in his first two books, another paperfolder, Mitsuhiro Uchiyama (often known as Michio) had developed a new and heavily cut style of paperfolding, known as 'kirikomi' or 'koko' origami. To Michio Uchiyama cutting slits into the starting shape of the paper was a good thing because it made the designs more efficient. Paper that would otherwise have been hidden, or, in his terms, wasted, inside the design could be brought out and used to create more realistic details. Information about Michio Uchiyama, his books and his designs is hard to come by, but an article by Peter Van Note in 'The Origamian' for Spring 1964 noted that 1933 was 'a memorable year in the Uchiyama household ... In that year Michio Uchiyama published 'Origami Kyohon' the first of his many books on paperfolding. And in September, his Koko-style origami was cited by an Imperial commission as 'an artistic and educational asset'. (Note that other sources give 1931 as the date of this book.) ********** Akira Yoshizawa At some time, probably after the publication of 'Origami', Isao Honda made the aquaintance of a much younger paperfolder, Akira Yoshizawa. We know very little about the true nature of their relationship, which was acrimonious in later years, but must have been reasonably friendly in the early days, because in 1944 Honda included a number of designs by Akira Yoshizawa in his book 'Origami Shuko'. These designs were two-piece, glued, compound models of animals (and possibly birds), a technique that Yoshizawa seems to have invented in order to provide his designs with the requisite number of points to produce four legs, a head and a tail, and were a significant departure from anything that had gone before. At this time Yoshizawa was otherwise largely unknown. He did not begin to become nationally famous until January 1952 when an article about his origami design work was published in the magazine Asahi Graf. This led to publication of a series of articles in 'Fujin Koron' (Ladies’ Opinion) magazine in April to December of the same year. Yoshizawa's first book, 'Atari Origami Geijuitsu' (The Art of Origami) was published in 1954. According to David Lister, in his introduction, Yoshizawa wrote that 'he had avoided the use of scissors because he did not want to transgress beyond the field of 'paper folding'', which was a stark contrast to the approach of Michio Uchiyama and perhaps set him apart from other paperfolders of his day. ???? Whe did he set up his first fan club ????? In many ways Yoshizawa's big break came about purely by chance, when a letter written to .............. by the American writer Gershon Legman, who also had a fascination with paperfolding and was researching the subject, was passed to Yoshizawa to respond to. The two men corresponded and in 1955, after Yoshizawa had exhibited his designs at the Ginza shopping centre in Tokyo, he sent many of the exhibits to Gershon Legman, who then arranged an exhibition of them at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. This exhibition, however, the first by a Japanese paperfolder in the West, went largely unnoticed, although, according to David Lister ( ) it was reported on favourably to his superiors by the Japanese Ambassador to the Netherlands. Gershon Legman then sent many of the same models to the USA where they were displayed, along with works by students and Western paperfolding designers, at an exhibition held in the Summer of 1959 at the Cooper Union Museum in New York. Once again, however, this does not seem to have resulted in any particular notice being paid to Yoshizawa's work by the general public. Meanwhile, in 1957, Yoshizawa had found a publisher for his second book 'Origami Dokuhon' (Origami Reader). This book was subtitled 'From play to creation' and was aimed at Mothers and Teachers. It is in two parts. The first part contains simple designs suitable for young children. The second part explains Yoshizawa's design philosophy of creative origami and shows how various types of more advanced designs can be produced and adapted. This book was quite influential among a small group of paperfolding aficionados who were loosely based around the New York Origami Centre of Lillian Oppenheimer. ********** Origami as Japanese Cultural Propaganda 1957 also saw the beginning of a new trend for the publication of books about Japanese paperfolding, or origami (as paperfolding was now frequently known), in the West, and particularly in the USA. The first of these were 'Origami: Japanese Paperfolding' by Isao Honda and 'Origami: Book 1' by Florence Sakade, all of which were published in 1957. Other books by the same authors followed in the next few years and they were joined, from 1962 onwards, by books by Tatsuo Miyawaki, and from 1965 on by books by Chiyo Araki. These colourful books, which mostly explained a fairly small number of quite simple designs, sold well and established the idea in the consciousness of the general public in the West that paperfolding (origami) was an oriental, and mostly a Japanese, art form. (It is interesting to note that although some of the models these books contain are traditional Western designs, imported to Japan along with the kindergarten, the authors are clearly not aware of this.) Some Japanese residents of the USA happily jumped on this bandwagon and gave classes and demonstrations of this artform across the country. We find, for instance, that ................., the daughter of the Japanese Ambassador to Washington, ...... Even the conceptual artist Yoko Ono, who was later to marry John Lennon, once made art of her living as an origami demonstrator. This idea that origami was a peculiarly Japanese artform was encouraged by the Japanese government, who were looking to find ways to rehabilitate Japan's international reputation after the damage done to it by the Second World War, and were actively promoting Japanese arts and crafts as away of achieving this. In ...... they appointed Akira Yoshizawa as ........... and, over the next ... years, arranged for him to visit many countries, including ................. to exhibit and teach his designs. In 1966 the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs made, as a propaganda tool, a film titled 'Origami: The Folding Papers of Japan' featuring Yoshizawa and many of his designs. ********** Toyoaki Kawai According to David Lister ( ), Toyoaki Kawai was once a pupil of Yoshizawa but became an author and teacher of origami in his own right, inventing many of his own original designs.

********** The Sosaku Origami 67 Group According to information received from Kunihiko Kasahara (private email), who was one of its nine members, the Sosaku Origami Group '67 (the Creative Origami Group '67) was established by ....

********** Kunihiko Kasahara As we have seen, Kunihiko Kasahara was a member of the Sosaku Origami Group '67 and had been a pupil of Kawai (and according to David Lister ( ) also of Yoshizawa).

********** References (1) 'Missionary Froebelians' Pedagogy and Practice: Annie L Howe and her Glory Kindergarten Teacher Training School' by Yukio Nishida, published online by Cambridge University Press on 7th April 2022. (2) 'The Black Forest in a Bamboo Garden: Missionary Kindergartens in Japan, 1868-1912' by Roberta Wollons, which was published in History of Education Quarterly , Spring, 1993, Vol. 33, No. 1 (Spring, 1993), pp. 1-35 |

|||||||