| The Public Paperfolding History Project

x |

|||||||

| Miguel de Unamuno - der Baskische Bildhauer by Edda Reinhardt, 1928 | |||||||

| 'Miguel

de Unamuno - der Baskische Bildhauer' (the Basque

Sculptor) by Edda Reinhardt, was published in Berlin in

the avante-garde magazine 'Der Querschnitt' in October

1928. This page contains the original German text, a Spanish translation published in issue 78 of the periodical 'La Gaceta Literaria', in Madrid on 15th March 1930, and an English translation kindly made by Edwin Corrie. **********

********** A translation into Spanish was subsequently published in issue 78 of the periodical 'La Gaceta Literaria', in Madrid on 15th March 1930, with an introduction by M.G.B.

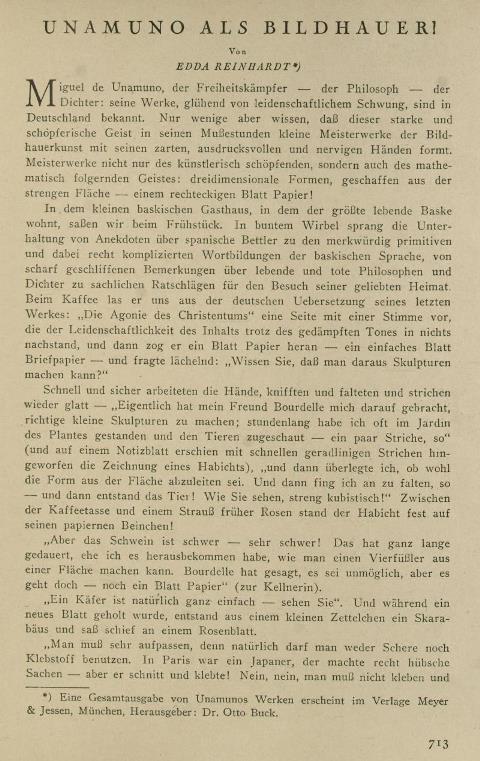

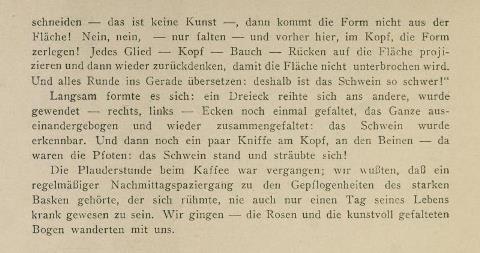

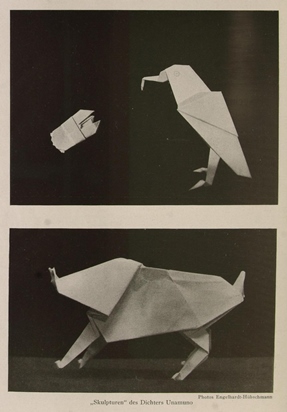

********** English translation by Edwin Corrie: UNAMUNO AS SCULPTOR by Edda Reinhardt Miguel de Unamuno, the freedom fighter – the philosopher – the poet: his works, blazing with passion and pizazz, are familiar in Germany. However, not many people know that in his leisure hours this strong and creative intellect uses his delicate, expressive and wiry hands to form tiny masterpieces of sculpture. They are masterpieces of a mind that is not only artistically creative but also skilled in mathematical reasoning: three-dimensional forms created from an austere surface – a square of paper! In the small Basque guest house where the greatest living Basque lives we were sitting eating breakfast. In a colourful whirl the conversation jumped from anecdotes about Spanish beggars to the curiously primitive and yet highly complicated word structures of the Basque language, from sharply polished observations about living and dead philosophers and poets to down-to-earth advice about the visit to his beloved homeland. Over coffee he read a page out loud to us from the German translation of his latest work: “The Agony of Christianity” in a voice which, despite the muted tone, was in no way inferior to the passion of the content, and then he took a sheet of paper – a simple sheet of letter-writing paper – and asked with a smile: “Did you know that you can make sculptures out of this?” Quickly and surely his hands went to work, wrinkling and folding and smoothing out again – “Actually it was my friend Bourdelle who showed me how to make proper little sculptures; often I have stood for hours in the Jardin des Plantes and watched the animals – a few lines, like this” (and on a sheet of notepaper, with a few quick straight lines, there appeared a drawing of a hawk), “and then I wondered whether it might be possible to take the form out of the paper. And then I started folding – and there was the animal! As you can see, very cubist!” Between the coffee cup and a bouquet of early roses the hawk stood firmly on his little paper legs! “But the pig is difficult – very difficult! It took me a long time to work out how to make a four-legged animal from a flat surface. Bourdelle said it was impossible, but it isn’t – another sheet of paper” (to the waitress). “Of course, a beetle is quite easy – look”. And while a new sheet of paper was being fetched a scarab appeared from a small scrap of paper and sat at an angle on a rose leaf. “You have to be very careful, because of course you’re not allowed to use scissors or glue. In Paris there was a Japanese man who made some really pretty things – but he cut and glued them! No, no, you mustn’t glue and cut – that’s not art – if you do, then the form does not come out of the surface. No, no – just folding – and first here, in your head, break down the form. Project each limb – head – belly – back – onto the surface and then think back again, so that the surface is not interrupted. And convert everything that’s rounded into straight lines: that’s why the pig is so difficult!” Slowly it took shape: one triangle after another, turning – right, left – the corners folded again, the whole thing opened up and then folded again; the pig came into view. Then a few more folds on the head, on the legs – there were the feet: the pig got up and stood to attention! Our little coffee chat was over; we knew that the sturdy Basque was accustomed to his regular afternoon walks, and boasted of not having been ill even for a single day of his life. We set off – the roses and the artfully folded sheets of paper walked with us. ********** |

|||||||